Cutting methane quickly is key to curbing dangerous warming, U.N. report says

- Share via

Cutting the super-potent greenhouse gas methane quickly and dramatically is the world’s best hope to slow and limit the worst of global warming, a new United Nations report says.

If human-caused methane emissions are cut by nearly in half by 2030, a half degree (0.3 degrees Celsius) of warming can be prevented by mid-century, according to Thursday’s report by the United Nations Environment Programme.

The report said the methane reduction would be relatively inexpensive and achievable — by plugging leaks in pipelines, stopping venting of natural gas during energy drilling, capturing gas from landfills and reducing methane from belching livestock and other agricultural sources, which is the biggest challenge.

Because methane helps make smog, cutting annual emissions of the gas by 45% or nearly 200 million tons (180 million metric tons) could potentially prevent about 250,000 deaths a year worldwide from pollution-triggered health problems, the U.N. said.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It is absolutely critical that we tackle methane and that we tackle it expeditiously,” UNEP Director Inger Andersen said Thursday.

Andersen said without both methane and carbon dioxide reductions, the world cannot achieve the goals laid out in the 2015 Paris climate agreement.

Indeed, the recent acceleration of methane pollution “is really taking us far, far off” the Paris goals, said study lead author Drew Shindell, an Earth sciences professor at Duke University.

Princeton University climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer, who wasn’t involved in the report and co-wrote a study last week on the gas, called methane “the best dial we can turn to slow the rate of warming.”

Scientists love a good mystery. But it’s more fun when the future of humanity isn’t at stake.

Methane reduction can provide short-term help in the long-term effort to curb global warming because it’s more potent yet shorter-lived than carbon dioxide, Shindell said.

Methane only lasts a dozen years in the air while carbon dioxide sticks around for centuries. There is 200 times more carbon dioxide in the air than methane. But per molecule, methane traps dozens of times the heat of carbon dioxide.

“If you think we are close to climate tipping points, methane cuts are a way to quickly reduce warming,” said Breakthrough Institute climate director Zeke Hausfather.

In Canada, stimulus spending is targeted toward controlling methane leaks, Andersen said. In the United States, the White House is working on new regulations to control leaks from energy production, Biden administration climate advisor Rick Duke said Thursday.

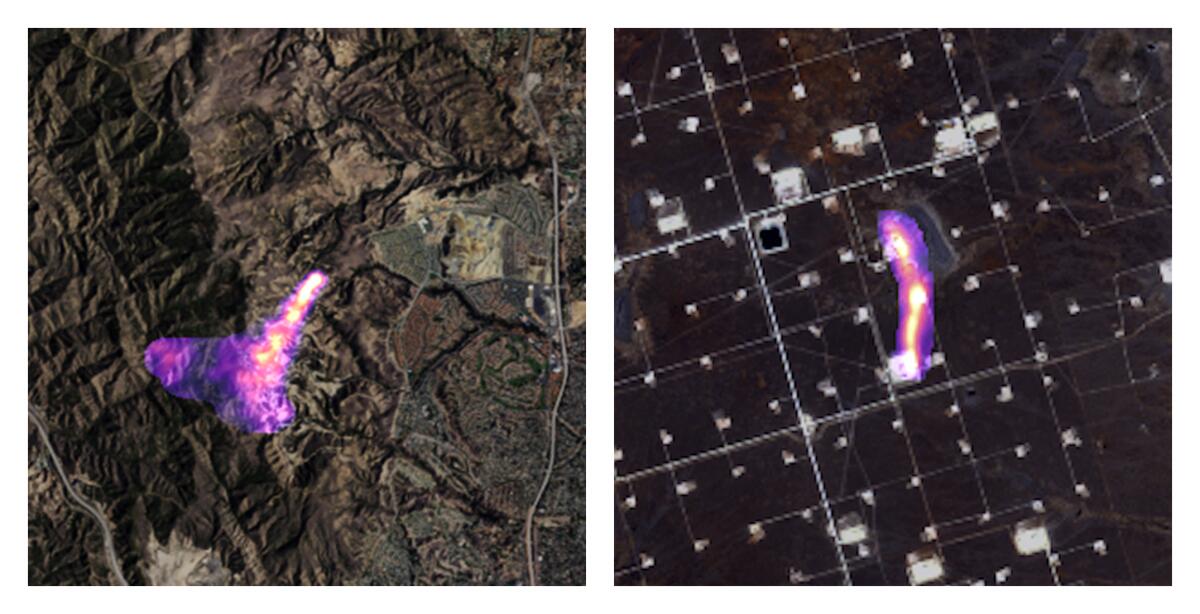

Shindell said satellites are showing massive energy-related leaks, especially in the United States and Russia.

“People are realizing that there is a lot more methane,” he said. “There’s a lot more of it that is coming from things that we know we actually have control over and can do something about.”

About 60% of the methane comes from human activity, with the rest from wetlands and other natural sources, the report said. Of the man-made methane, about 35% escapes from drilling and transport of natural gas and oil, 20% seeps out of landfills and 40% comes from agriculture, mostly livestock.

Usually, choosing between the lesser of two evils is a dismal decision.

The natural gas that escapes has value, so capturing it from energy production and landfills makes financial sense, scientists say.

“I think of every methane leak as an invisible stream of tiny dollar signs,” said Stanford University environmental studies director Chris Field.

The report says cutting food waste, improving how livestock is fed and adopting diets with less animal products can spare the planet up to 88 million tons (80 million metric tons) of methane a year.

James Butler and three other scientists who study methane emissions for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said they fear recent methane increases “might be driven by climate change” because warming temperatures could be releasing methane normally locked in the ground.