Fire suppression fueled California’s destructive 2020 blazes, study says

- Share via

The 2020 wildfires that incinerated a record 4.3 million acres in California harken to centuries past when huge swaths of the state burned annually, researchers have found, but today’s climate-driven conflagrations are far more destructive to the environment and human health.

“California is in for a very smoky future, and the continued resilience and even persistence of numerous terrestrial ecosystems is not assured,” concluded a new study published in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography.

The state’s Mediterranean climate, with its normally wet winters and dry, hot summers, has primed California to burn throughout its history. Before colonization, though, such wildfires helped keep the state’s vast forests healthy by burning underbrush and triggering trees to release their seeds, according to scientists.

The 2020 wildfires marked a turning point. Fires burned 4.2% of the state that year, about the acreage annually consumed by fire before European and American settlement. But a century of fire suppression has left California with what the researchers call a “massive fire deficit” as forests become choked with trees and undergrowth.

The payback in 2020 was devastating. All that fuel, rising temperatures, drought and high winds dramatically increased the intensity and speed of wildfires, which burned 2.2 times more land than the previous record set only two years earlier.

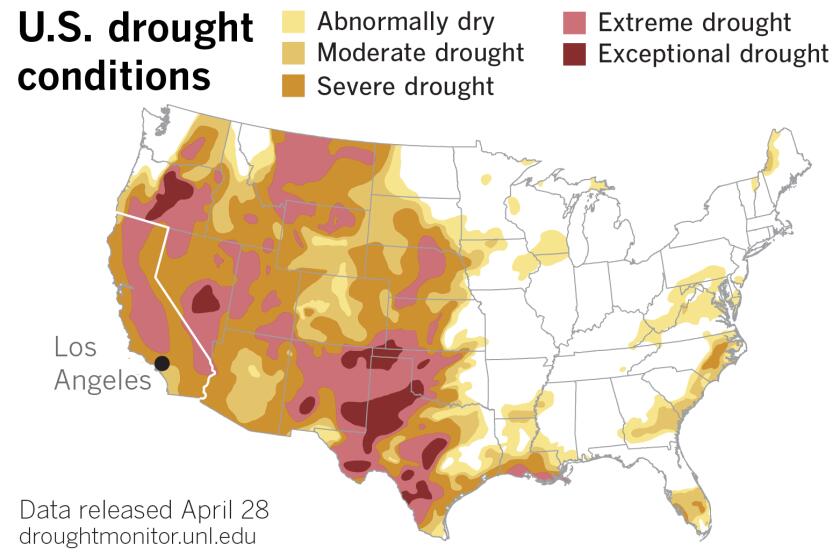

La Niña was expected to dissipate, but it may linger through the summer. That’s bad news for drought and wildfire-prone California.

Firefighting costs neared $2.1 billion and the wildfires caused $19 billion in economic losses and 33 deaths. Fires burning hundreds of miles away blanketed the heavily populated San Francisco Bay Area in a layer of toxic smoke so thick it turned the sky an apocalyptic shade of orange. Scientists expect exposure to particulate matter in the smoke to lead to thousands of premature deaths over time.

“It’s a return to the past and a harbinger of the future,” said wildfire expert Hugh Safford, the lead author of the paper and a researcher at UC Davis. “I don’t think you can get away from this strong inertia of forests burning.”

The researchers correlated the severity of wildfires in 2020 with how much time had lapsed since forests and chaparral last burned. In many cases, forests had not burned for more than a century, and as a result the fierceness of the fires destroyed so many trees that some woodland ecosystems may not recover.

“We’re going to be transitioning into dryland-type ecosystems that are dominated by shrublands, and grasslands,” said Safford, a retired U.S. Forest Service ecologist. “In 50 to 60 years, Northern California could look like parts of Southern California if we keep going in this direction.”

“In 50 to 60 years, Northern California could look like parts of Southern California if we keep going in this direction.”

— Hugh Safford, University of California, Davis researcher and lead author of the paper

Climate change has set the trajectory of more widespread wildfires in California and experts expect a record-breaking drought, diminishing snowpack and heat waves to make for a potentially catastrophic wildfire season this summer.

The researchers called for a change in government strategy that has long focused on reducing the amount of land burned by wildfires. Instead, they said, the priority should be on lessening the severity of fires and restoring ecosystems of burned areas.

That would require a huge investment in thinning overgrown forests that fuel out-of-control wildfires while under the right conditions, letting fires burn in wilderness areas that are inaccessible due to steep terrain.

“We know what to do,” said Safford. “We’ve known for 60 years that fire is an escapable and integral part of these ecosystems.”