Why can’t smoggy SoCal improve air quality? Local regulators blame the federal government

- Share via

With smoggy Southern California poised to miss a critical clean air goal next year, local regulators are now threatening to sue the Environmental Protection Agency, saying the federal government has made their job “impossible.”

The South Coast Air Quality Management District recently notified EPA Administrator Michael Regan that it intends to sue the agency for violating the Clean Air Act unless it agrees to adopt new regulatory strategies that would curtail pollution from federal sources, including ocean-faring cargo ships, trains, out-of-state trucks and airplanes.

The notice marks a tense new chapter in the district’s 20-year struggle to meet a federal standard set in 1997. If Southern California fails to meet those standards in 2023 — which is all but certain — federal authorities may impose severe penalties, such as the withholding of certain transportation funds.

Although state and local regulators have made considerable progress in curbing smog-forming emissions since 1980, that progress has leveled off in recent years. As a result, Southern California has sought repeated deadline extensions from the EPA.

Three years ago, when it was evident the air district would fall short of the Clinton-era benchmark, AQMD called on the EPA to set cleaner standards for trucks, trains and ships visiting California. The EPA has yet to act on that request, however.

“Even if we were to have zero emission for all of the stationary sources in our region, we would not be able to come into attainment,” said Wayne Nastri, the air district’s executive officer. “And so this really speaks to the need for the federal government to stand up.”

The state had accused Fontana officials of violating the environmental review process when it approved a large warehouse next to a high school.

Although new federal emission reductions would be welcome by environmental groups, some observers criticized the move as an 11th-hour gambit that was unlikely to result in substantial air quality improvements by next year.

“If you’re a breather in the region, it’s pretty outrageous what’s happening,” said Adrian Martinez, senior attorney for Earthjustice, an environmental nonprofit based in San Francisco. “In 2007, these agencies came together and put together a plan saying, ‘Hey, trust us, we’ll solve this problem.’ Fast forward 12 years, they say, ‘Oh, here’s our contingency plan when we don’t meet the standard.’”

The South Coast air district — a 6,700-square-mile basin spanning Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside and Orange counties — has long held the title as the smoggiest region in the nation. Since 1979, the air district has not been in compliance with any of the several federal standards for ozone, the lung-searing gas commonly known as smog.

The air district’s legal threat has highlighted the unique challenge of regulating air pollution in Southern California. No fewer than three government agencies are tasked with overseeing air quality for the region’s nearly 18 million residents. They include the local air district, which regulates emissions from major polluters, such as power plants and oil refineries, within their borders; the California Air Resources Board, which regulates in-state cars, trucks and off-road equipment; and the EPA, which has oversight over interstate and international travel and commerce.

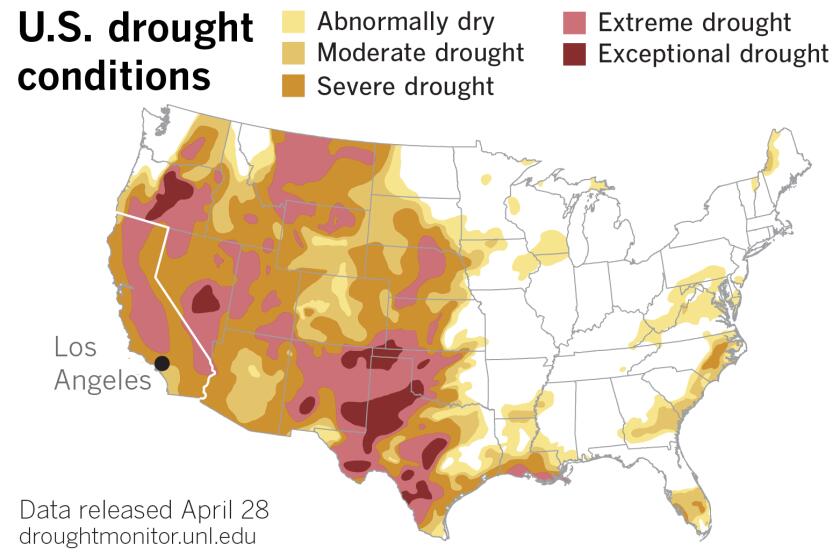

La Niña was expected to dissipate, but it may linger through the summer. That’s bad news for drought and wildfire-prone California.

Failure to comply with federal standards could result in a variety of sanctions. In addition to the potential loss of billions of dollars in federal highway funds, businesses could face new challenges when they seek permits from the district.

“These (permitting) hurdles are pretty high — so high we think it would effectively result in a permit moratorium in our areas,” said Sarah Rees, a deputy executive officer at the air district. “That would mean new businesses or existing businesses that want to make modifications would be unable to get permits to be able to do that.”

In the April 15 letter to the EPA, the air district’s general counsel Bayron T. Gilchrist argued it would be unfair to penalize the South Coast for its inability to comply.

Without federal intervention, the only way state and regional officials could meet the air quality standard would be to eliminate emissions from all buildings, power plants, industrial facilities, and state-regulated vehicles and greatly reduce emissions from large farming and construction equipment. That isn’t a feasible option by 2023.

As dams and global warming push endangered California salmon to the brink, a rescue plan is taking shape — and a tribe pushes for recovering their sacred fish.

Smog-forming nitrogen oxides are released into the atmosphere when fossil fuels are burned.

Between 2012 and 2023, emissions of nitrogen oxides in the region will have been slashed nearly 50%, Gilchrist wrote. But “almost all these reductions” will come from cleaner vehicles regulated by the California Air Resources Board and facilities regulated by the AQMD, the letter said.

Meanwhile, sources of pollution under federal oversight are trending upward, according to the air district. Emissions from aircraft, locomotives, and ocean-going vessels are expected to increase by almost 10% over that same 10-year period ending in 2023.

The air district estimates the region needs to eliminate 128 tons of nitrogen oxides per day in order to comply with the 1997 ozone standards.

The twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach — collectively the largest in the nation — is the largest fixed source of air pollution in Southern California, according to AQMD. The ports, where 40% of the nation’s imports arrive aboard diesel-belching ships, are responsible for more than 100 tons per day of nitrogen oxides — more than the daily emissions from all 6 million cars in the region.

The EPA declined to comment on the potential litigation, but noted that a proposed federal rule for heavy-duty trucks, which aims to reduce nitrogen oxides by as much as 60% in 2045, could benefit the region.

“EPA does recognize the challenges being faced by South Coast — it is very difficult to chart a path to attainment when more reductions are needed from trucks, rail, aircraft, ocean-going vessels, and other mobile sources,” EPA spokesperson Taylor Gillespie said. “EPA is doing our part to achieve attainment in this air district; our recent proposal to set new emission ... limits for heavy duty trucks is a step in the right direction.”

South Coast officials say it’s not enough.

“Many of the rules that EPA should be doing on mobile sources — on locomotives, on ships, on aircraft, on construction equipment — they’ve lagged,” Rees, the AQMD deputy executive officer said. “They haven’t kept pace with regulation from stationary sources. But on the truck rule, itself, EPA … predicted we’ll still be way above ozone standards. So even with that most stringent option in place, the truck rule is you know, 50 years after the 1997 ozone standard, South Coast is still going to be out of attainments — and pretty far out of attainment.”

Southern California’s legacy of unhealthy air is owed, in part, to bustling ports, warehouses, airports and congested highways. The region’s bustling economy and infamous traffic have always contributed high amounts of nitrogen oxides. The situation is compounded by the region’s perpetually sunny climate, which effectively cooks vehicle exhaust and industrial emissions into lung-damaging smog and a mountainous terrain that confines the toxic haze over the region.

And now, in addition to pollution, regulators are contending with climate change, conditions scientists say could lead to a smoggier future.

Sunlight and heat are the catalysts for smog formation. As the levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases have spiked due to burning of fossil fuels, Southern California has witnessed record-breaking heat.

In 2020, a year marked by blistering heatwaves in August and September, there were 157 bad air days for ozone pollution — the most days since 1997, according to AQMD records. Perhaps most notably, on Sept. 6, 2020, temperatures climbed to 121 degrees in Los Angeles County and ozone concentrations spiked to 185 parts per billion in downtown Los Angeles, making it the hottest day on record and the smoggiest in downtown in 26 years.

“As the temperature increases — everything else being kept the same, like emissions of pollutants — then it’s going to be harder for the South Coast to meet their ozone standards,” said Anthony Wexler, director of the Air Quality Research Center at UC Davis.

The air board must also achieve even more restrictive targets for ozone by 2031 and 2037. Until the federal standards are met, residents will continue to brave unhealthy levels of smog.

“It’s like at some level I think we’ve been lied to,” said Martinez, the Earthjustice senior attorney. “Like from the beginning that this is just a sham. It’s fantasy. … And who suffers? It’s breathers. It’s the people in the Inland Empire who have 100 days of summer blanketed in smog.”