Throwing the book at ‘Thieves of Book Row’

- Share via

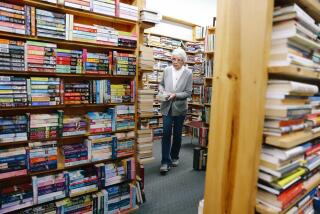

It is hard to imagine a more gentlemanly trade than the buying and selling of old books. The very word “antiquarian” evokes tweedy, bespectacled fellows moving between dusty shelves to pull down some esoteric intellectual treasure. But as Travis McDade shows in “Thieves of Book Row,” book dealing in the early 20th century was rife with scoundrels and rogues.

Book prices soared in the 1920s, then plummeted in the Great Depression, “when a difficult industry was made nearly impossible,” McDade writes. “Booksellers did what they could to survive, ranging from the mildly unethical to the outright criminal.”

Most sellers of used books plied their trade on Book Row, on New York’s Fourth Avenue between Astor Place and Union Square, with a few boutique shops uptown. The ecosystem stretched from penny paperbacks to rarities worth thousands, and a used book would often pass through the hands of multiple shop owners on its way to a collector such as Jerome Kern.

When Kern’s collection was auctioned in January 1929, collectible book fever was so high that it set price records that lasted 50 years. The most expensive item was Percy Bysshe Shelley’s revised poem “Queen Mab,” which sold for $68,000 — the equivalent of $913,000 today.

Prices like that made dealers hungry for stock, but used books don’t grow on trees. They could, however, be easily harvested from libraries, a practice that dated to the Victorian era. It was an open secret on Book Row that many of the suppliers of collectible books were filching them from library shelves, and by the 1920s, a number of bookstore owners were actively involved in the process.

In the spectacular theft at the center of the book, robbers nabbed “Moby-Dick” by Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems” from the New York Public Library. The Poe is so rare that McDade, the curator of rare books at the University of Illinois College of Law, says he cannot estimate its value.

“Al Aaraaf” and the other two books were stolen on a busy Saturday in 1931 from the library’s well-protected reserve book room. Authorities were so close to catching the thieves they could see the coattails of the last one flapping as he raced away.

That thief was Samuel Raynor Dupree, a novice accompanied by more experienced biblioklepts he knew only as Paul and Swede. With names like that, McDade’s story takes on the quality of a 1930s gangster film. One book dealer who organized thieves was William “Babyface” Mahoney. When the ring was finally busted, it didn’t sound bookish at all: The papers called it the Romm Gang.

McDade does a superb job of drawing a complete picture of the environment in which the Romm Gang operated. Charles Romm was a respected book dealer who had connections to less respectable book dealers, who managed a rotating cast of book thieves. In a scheme that stretched to the 1800s, a fleet of ne’er-do-wells and slightly nefarious scholars had walked into libraries, pocketed books (literally), and then scrubbed them of the markings that indicated ownership.

Libraries defended their stock, pulling valuable holdings out of circulation, hiring guards to sit by the exit, and adding more complex markings. Thieves were most challenged by the markings — removing them took a skilled hand.

To bring the practice of stealing rare books to an end, someone had to line up thief, scrubber, fence, buyer and stolen property all at once. The man who did it was G. William Bergquist, a kindly World War I veteran who was the NY Public Library’s chief investigator. McDade tries to make a hero of Bergquist, but the criminals, with their gangster-style monikers and other peculiarities, are almost universally more interesting than the library lawman.

For the most part, however, McDade makes a smart choice to spin his tale around the mostly forgotten individuals who participated in a widespread scheme to steal library books. Yet he’s not particularly sympathetic to them: he bristles at their audacity, their greed, and the offense itself, stealing books from public libraries for private gain.

For bibliophiles, the story isn’t over. In addition to the maps, guides, and firsthand accounts of early Americana that were frequently stolen, thieves also filled their coats with books by writers we still consider great. Mark Twain, James Fenimore Cooper, Emily Dickinson, Thomas Paine, Henry David Thoreau, Harriet Beecher Stowe and many others were stolen.

While the NY Public Library got its “Al Aaraaf” back, “The Scarlet Letter” and “Moby-Dick” were never recovered. They — and many other valuable classics that used to sit on library shelves — may well be sitting in personal collections today.

Thieves of Book Row:

New York’s Most Notorious Rare Book Ring and the Man Who Stopped It

Travis McDade

Oxford University Press: 240 pp., $27.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.