Is sustainable ground beef safer? Not really. Here’s why

A Consumer Reports investigation considered the merits of ground beef.

- Share via

There’s nothing like the phrase “fecal contamination” to get your attention. And most of the reporting on an investigation by Consumer Reports magazine into the safety of ground beef from sustainably vs. conventionally raised animals published this week certainly took advantage of that.

As the New York Daily News so eloquently phrased it: “Here’s some crappy news: There’s poop in your beef.”

But that kind of response undercuts the seriousness of the magazine’s effort. The 50-page full report is worth reading in its entirety. There are many reasons to consider buying more sustainably raised beef — animal welfare, ecology, supporting small farmers. But as it turns out from a close reading of the report, bacterial contamination probably isn’t one of them.

In fact, despite the flamboyant headlines, it’s doubtful whether any of that meat was actually harmful, particularly if it had been properly handled and cooked.

>>McDonald’s rejects Burger King peace offer

To recap the CR report: The magazine purchased 300 samples of ground beef at various markets across the country. Some came from packages that made some kind of sustainability-based claims about how the cattle were raised (“grass-fed,” “organic,” “no antibiotics”); others came from conventionally raised cattle (there were no special claims made on the package labeling).

The magazine then tested the samples for a variety of factors, including what type of bacteria were found, whether they were harmful and whether they were antibiotic-resistant. To be clear, there was no fecal matter found, only bacteria that can be associated with it.

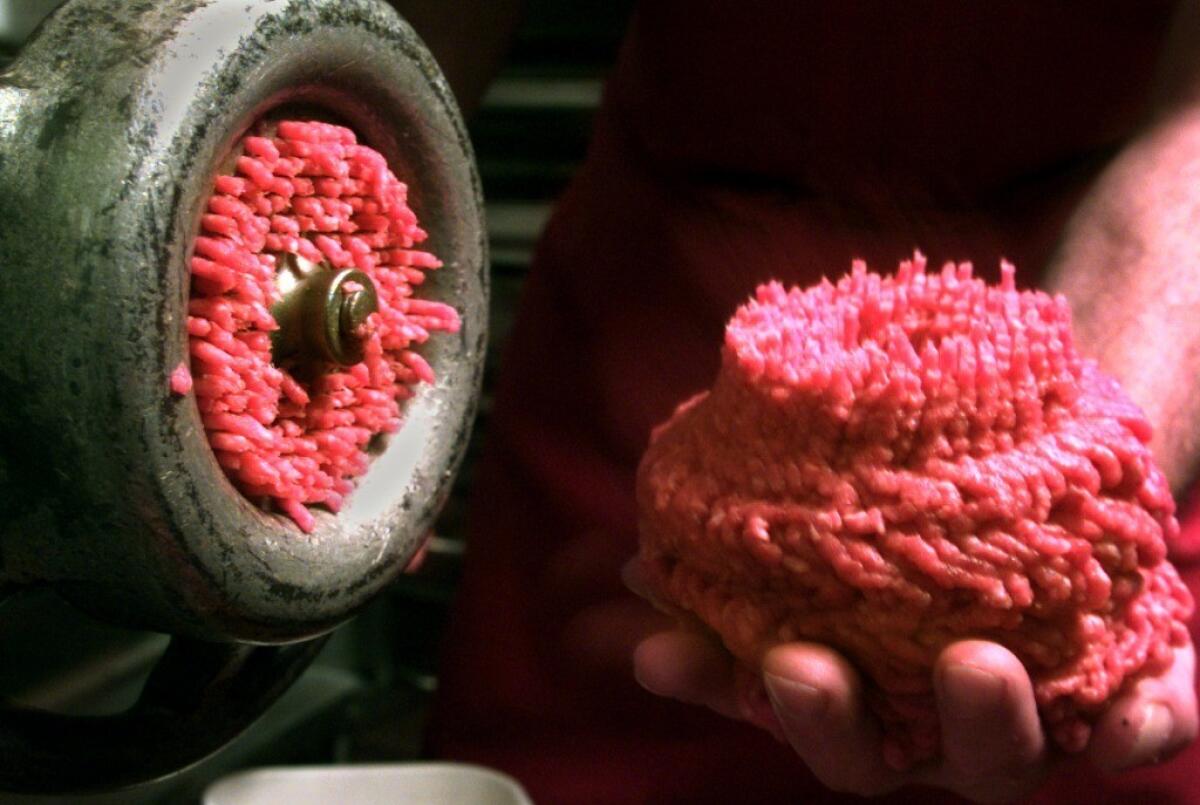

Ground beef is considered an especially troublesome food-safety concern. Most bacteria are found only on the surface of cuts of meat, where it can be easily cleaned, or where it can be quickly heated during cooking, killing it.

But when that whole cut of meat is ground, that surface bacteria can be distributed through the entire batch. And because ground beef typically comes from trimmings collected from many different animals, one mistake can quickly multiply.

The magazine found at least one type of the bacteria that can be associated with fecal contamination — Staphylococcus, Clostridium, E. coli and Salmonella — on every sample it tested (and two or more types of bacteria on almost three-quarters of the samples).

But the report also claimed “significant differences … between conventionally produced beef and beef that was more sustainably produced” in the amount of contamination present, with sustainably raised beef — which, the magazine points out, is estimated by the Department of Agriculture to cost $4 to $5 more per pound — often coming out significantly ahead.

However, there also were important caveats that went largely unreported in the hullabaloo over “fecal contamination.”

For example, most of the bacteria found on beef is introduced during or after slaughter, not when the animal is being raised. Because sustainably raised beef tends to go to smaller specialty slaughterhouses, any difference in contamination rates is probably a stronger argument for smaller processing facilities rather than a specific feeding program.

The report found that conventional beef samples were twice as likely to be contaminated with Staphylococcus aureus (an especially tricky bacteria because it can produce a toxin that is not destroyed by cooking). But only certain strains of S. aureus are capable of creating the dangerous toxin, and when it came to those strains, the magazine found that the differences between conventional and sustainable beef were not statistically significant.

The tests also found Clostridium perfrigens bacteria on 19% of the samples. This is an especially prevalent bug that can produce a toxin that is responsible for about 1 million cases of food-borne illness every year. But none of the bacteria found in CR’s tests were of the type that produce that toxin.

When it came to E. coli and Salmonella, the stories were similar. Though the report found E. coli, it was not the kind that causes illness. And the Salmonella was extremely rare — in only 1% of samples.

When it came to antibiotic resistance, a huge and growing issue for human health, though conventional samples were twice as likely to harbor bacteria that were resistant to more classes of antibiotics than the sustainably produced samples, most of those were for antibiotics that are used for livestock production only.

None of this is to suggest that buying sustainably raised meat is not a valid option, even when it is $4 to $5 a pound more expensive. That’s especially true because the American meat market has become so consolidated (as the magazine points out, 75% of all of our beef comes from just four companies).

Indeed, if you are interested in buying more sustainably raised beef, the report is probably strongest when it comes to analyzing what the different labels mean — and don’t mean. “Animal Welfare Approved,” “Animal Welfare Approved Grassfed” “Demeter Biodynamic,” “GA- Step 5-5+” and “PCO Certified 100% Grassfed” were considered the best.

But these are complicated issues and deserve a careful weighing. Reducing them to “there’s poop in your beef” adds nothing to that discussion.

Are you a food geek? Follow me on Twitter @russ_parsons1

ALSO:

Eggplant: To salt or not to salt?

What’s best at the farmers market right now?

Five great after-school snacks you can make in a hurry

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.