In Providence’s kitchen: Using the whole fish and talking about preventing food waste

- Share via

There was a rhythm to the kitchen on a recent Thursday afternoon as cooks prepared for the evening’s service at Providence, the Hollywood seafood restaurant that’s been No. 1 for the last few years on Jonathan Gold’s 101 Best Restaurants List. The kitchen is a finely tuned machine, a model of efficiency. In one corner, a pastry chef made sakuramochi, folding pastel pink rice cake and red bean paste around house-pickled cherry leaves. A cook who’d just harvested edible flowers from the restaurant’s roof garden divided them into portions, each to serve as a garnish for the night’s dishes.

“That garden changes the way we do things, and a big part of the inspiration was to eliminate waste,” said Michael Cimarusti, Providence’s chef and owner. When they’d order flowers from a farmer, they’d need to cull through the order to pull what they wanted, and the rest would be wasted. By growing the plants on the roof, cooks pick only what they use each day.

As Cimarusti walked through the kitchen, he compared the operation to a home kitchen — just on a much larger scale. “We try to thin out what we bring into the house and streamline as much as we can.”

Cimarusti opened one of the ovens. Inside, a sheet of scallop beards and adductor muscles — trimmings from cleaning whole scallops for service — were baking. Once dried, they’ll be used to make a scallop broth. “Drying them out makes the flavors that much more intense,” he said. The broth might be used to simmer a vegetable or slowly braise a grain, such as buckwheat. And the scallop livers? They might flour and sauté them.

“Bringing in whole animals — in our case, whole fish — limits food waste,” said Cimarusti. They’ll use the bones, the skin, the shells — every part. “We find multiple uses for things that might otherwise end up in the trash.”

Box crab

Passing a fish tank, Cimarusti picked up an odd-looking crab. “It’s a box crab,” he said, smiling. “It was picked up on along the coast in Santa Barbara. Who knew it even existed? It’s not much to look at, but it has great flavor.”

Cimarusti walked to the back of the kitchen, entering a small room known as the “fish box.” Inside, two cooks were breaking down fish for the night’s dinner. On the counter sat a small pile of cooked box crabs. Cimarusti broke open a leg, pulling out the meat. “You could put that crab up against pretty much anything. It’s not as pretty as the more highly prized Dungeness, but I don’t think you could want for flavor.”

Columbia River king salmon

Turning to another counter, Cimarusti pointed to three good-sized salmon — with their skin shimmering in the light, they looked like they just came out of the water. The king salmon were from the first spring run of the Columbia River.

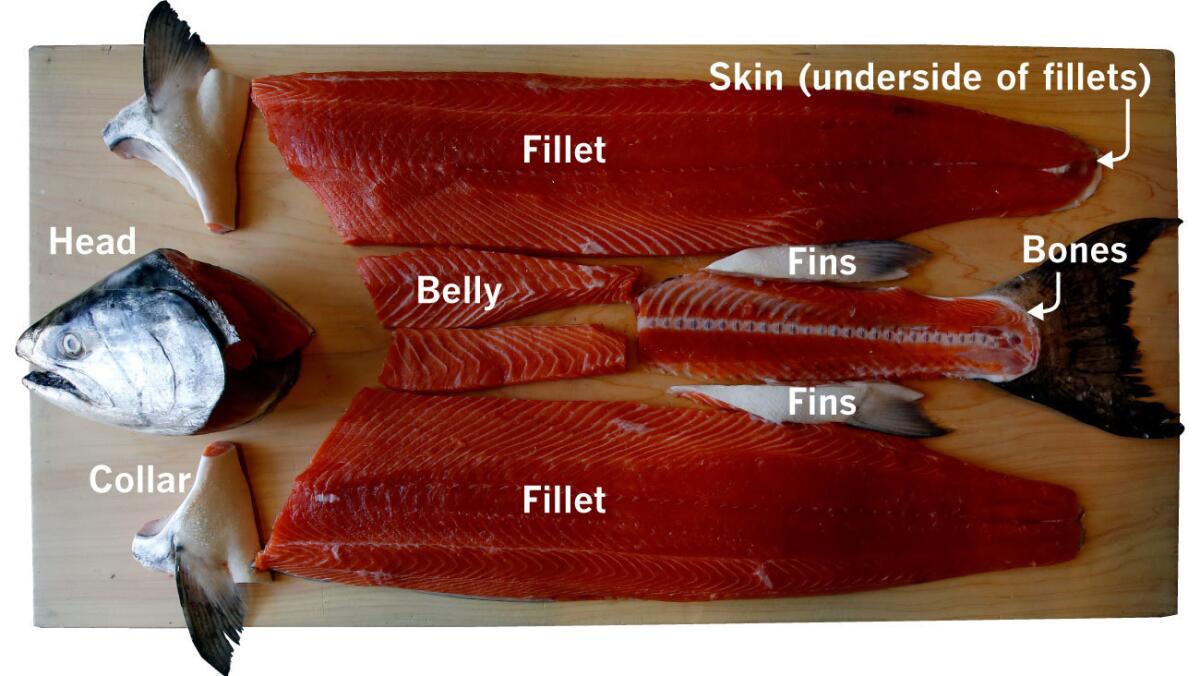

He watched as chief fishmonger Francisco Hernandez began to break down the fish, first cutting off the head, then separating the collar behind the skull into two pieces. Within minutes, he was filleting the fish, running the knife down the length of the fish as if slicing through butter.

He took off the first fillet, an intense shade of red, then the second fillet, trimmed the pieces, then sliced off the tender belly and the two fins. “You wouldn’t think of using the fins,” said Cimarusti. “You have to pick the meat out, but it has so much flavor.”

When he was done, Hernandez had broken the fish into seven usable components: fillets, skin, bones, collar, belly, head and fins.

King salmon uses:

- Fillets: One of the easiest parts to use and one of the most commonly cooked at home. Cooking options include sautéing, grilling, pan-roasting, oven-roasting, smoking and braising.

- Skin: If left on the fish, sear the skin so it crisps before serving. If removed, dry out the skin, then puff it using a broiler, or deep-fry it to use as a garnish. Cimarusti explains that in Japanese cuisine the skin is often simmered in a small amount of water, then chilled to form a sort of gelée.

- Bones: These can be used to flavor stocks and broths.

- Collar: One of the most flavorful parts of the fish. Cimarusti likes to cook it over a charcoal fire, then pull off the meat to add to tacos or salads.

- Belly: Often one of the most prized parts of the fish because of its high fat content, the belly is often used for sashimi or tartare. Cimarusti also likes to smoke or sauté it.

- Head: Cimarusti loves to use the heads to make head cheese. Remove the gills, then boil the head and pull off the meat. The liquid has enough gelatin on its own for a basic cheese. Or after boiling the head, flavor it and mold the meat as a terrine.

- Fins: Cook the fins, then pick out the meat. Cimarusti says that in Japanese cuisine the fins are often dried out and infused in sake before serving.

Cold-smoked salmon with rolled salmon skin

Cimarusti likes to serve the salmon skin as part of an amuse buche at the restaurant. First, the skin is scaled and cleaned, then it’s slowly baked with olive oil and salt between layers of parchment until it dries out. Cooks trim each piece of skin into a small rectangle and place it under a broiler to heat. As the skin is heated, the fat begins to render, and the skin puffs up and begins to crisp. Then a cook will carefully mold the rectangle to form a straw.

Once formed, a paper-thin piece of cold-smoked salmon fillet is wrapped around the tip of the straw over a layer of lemon whipped cream and garnished with a sprinkling of finely diced egg yolks, whites, red onion and diced chives.

Seared salmon belly

Cimarusti took one of the trimmed belly pieces, with the skin on, and seasoned it simply with salt. He heated a pan over high heat and added a thin film of butter. After carefully laying the fish in the pan, skin-side down, he waited for the belly to sizzle, then removed the excess fat. “The salmon will begin to render its own fat, and you don’t want too much fat in the pan,” he said. As the skin cooked, Cimarusti placed a small metal container filled with ice water on top of the belly — this prevents the belly from cooking too much as the skin crisps, so the flesh stays rare.

When the belly was done, he cut the piece into perfectly shaped cubes and arranged them on a plate. A cook placed braised morel mushrooms and baby turnips around the fish, added compressed turnip leaves, powdered green tea and a drizzle of a green tea and turnip purée — and, finally, delicate miner’s lettuce tendrils and blooms.

Grilled salmon fillet

Cimarusti sliced a center fillet and brushed it with a very thin layer of mayonnaise “so it’s almost not there.” He seasoned the fish simply, with a sprinkling of salt, and placed it over a Japanese charcoal grill. After a minute, he added soaked applewood chips and carefully moved the fish up and down over the heat. Once done, he set the fish aside to rest as he composed the rest of the dish.

Cimarusti spooned a layer of pickled ramp greens with lemon segments, olive oil and capers onto a plate. He placed caramelized, peeled Japanese sweet potato halves on one half of the plate; the skins, fried separately as chips, were arranged around the potatoes. The salmon was added to the dish, which was finished with ramp leaf “chips” and a ramp-infused sauce.

Asked about his inspiration when it comes to creating dishes and utilizing ingredients, Cimarusti largely credited his time at Le Cirque in New York. “After a couple of years working at Le Cirque, the chef became more comfortable with me, and he would allow me and the other chefs de partis to come up with ideas and incorporate them into the daily menu.” When Cimarusti left New York for Los Angeles, he spent time at the original Spago before taking a position at the Water Grill in downtown.

“That was it. Once I started at the Water Grill, fish was all I ever dealt with and all I ever wanted to deal with.”

In addition to Providence, Cimarusti’s fine-dining restaurant, Cimarusti owns and operates the more casual Connie & Ted’s in West Hollywood and Cape Seafood, a retail fish market in Los Angeles. Much of the fish each operation uses comes through Dock to Dish, a community-based seafood sourcing program that connects subscribers directly with locally caught seafood similar to community supported agriculture, or CSA, programs.The operation, originally started in Montauk, N.Y., expanded to California just a couple of years ago, and Providence was the first subscriber.

Whatever is harvested is delivered to restaurants, and, as with the box crabs, Cimarusti still comes across animals he’s never used before. Cimarusti explained that the fish that are often delivered are not marquee species and are certainly not fish that would be found through a regular retailer. “Some have never seen the light of day.” Still, he thrives on the challenge and potential they bring.

“When it comes to retail fish, the majority of demand is put on basically four species: tuna, salmon, sea bass and shrimp,” said Cimarusti. Even with the advent of aquaculture and the way it’s currently performed, Cimarusti believes it’s not enough to supply the world’s demand without compromising quality and environmental impact and flavor. “We have to diversify our demands,” he said. “There are all sorts of incredible species out there that are underappreciated and underutilized and also delicious and worthy of our attention.”

Taking food waste to a larger level, Cimarusti ultimately hopes consumers reevaluate their tastes and what they might be looking for, particularly when it comes to seafood. He’s practicing this at his operations. “You might not come to Providence and expect to eat a black gill rockfish,” he said, “but if you prepare it properly, it’s as flavorful as any of the marquee species anyone out there would be looking for.

“That’s the beauty of it.”

ALSO

Why we need to stop throwing out food and thinking of it as a resource

Food Bowl is coming. Here’s our cheat sheet of what to do during the monthlong festival

Can urban farming combat food waste? We chatted with the founders of Alma Backyard Farms

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.