Restaurants are pivoting to takeout and delivery. Will it be enough to survive?

- Share via

As fallout from the coronavirus pandemic began to hit the dining industry, delivery companies offered a rare concession to their restaurant partners.

Delivery app Postmates Inc. said Tuesday it would waive commission fees for small businesses in San Francisco that sign up for a relief pilot program.

On Friday, competitor Grubhub Inc. announced it would “suspend collecting up to $100 million in commissions from independent restaurants across the country.” UberEats announced Monday it would waive delivery fees for orders from independently owned restaurants using its service.

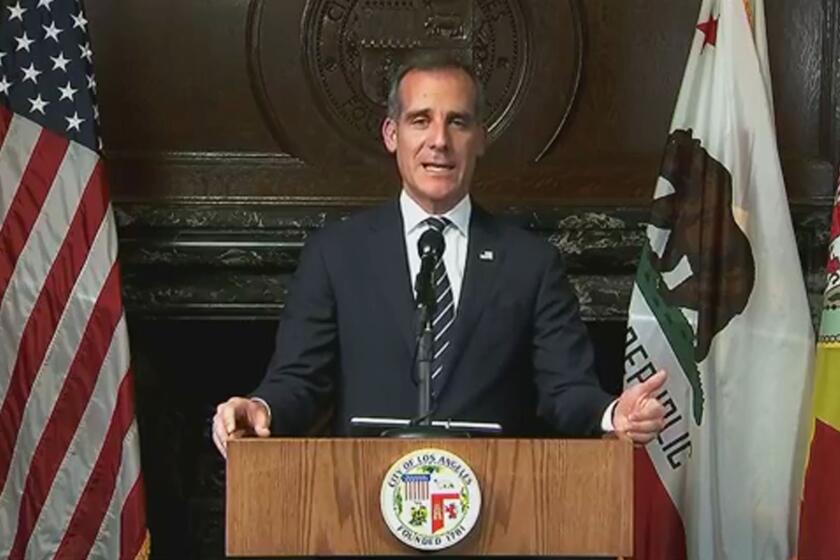

Los Angeles bars must close and restaurants must stop dine-in service in an effort to slow the spread of coronavirus, Mayor Eric Garcetti said Sunday night. Restaurateurs and bar owners fear many establishments might not reopen.

It’s a change that will offer restaurants much-needed relief, as new rules barring dine-in service in Los Angeles and other major cities have forced food establishments to adapt. Delivery and takeout services that once offered additional revenue streams have become their sole means of survival.

But waived fees by delivery apps may not be enough to ease the transition. For many restaurants, quickly shifting to a takeout or delivery-only business model isn’t easy — nor is it necessarily profitable.

Restaurants are known for high overhead costs and relatively narrow margins, which puts them in a precarious position. Businesses unable to adapt quickly may be forced to shutter, and the L.A. restaurant landscape could look dramatically different when the dust settles, chefs and proprietors say.

“There is no way delivery and takeout can work to sustain a business, unless your business was already designed for that,” Jon Shook, chef/co-owner of Jon & Vinny’s, Animal and other high-profile restaurants in L.A., said. “You can’t pivot all of a sudden and expect to cover such a huge cost difference.”

So far, Grubhub and UberEats are the only companies that have publicly committed to the temporary suspension of fees, which often are as high as 30%. Requests for comment from DoorDash Inc., and Caviar Inc. were not immediately returned. Monday morning, Postmates said it was “pursuing ways we can expand our merchant relief pilot program” to other cities.

Chase Valencia, co-owner of Lasa, said that even as he transitioned his 50-seat Chinatown restaurant to focus on fulfilling delivery and takeout orders, he was doubtful that sales would be enough to cover his monthly rent, let alone labor or other costs.

“Not only is delivery expensive for customers, on our end you end up paying a third to the delivery company. So if we charge $14 for a rice bowl, we’re only seeing $9,” Valencia said.

“Adding to that, you now have a huge number of other businesses competing for those same orders, many of which have never done business in that space before. It’s going to be a mess.”

Complicating matters further is exposure to the delivery drivers themselves, the majority of which are gig workers with limited access to health insurance and other benefits.

As demand for drivers has surged in California, Washington state and New York, delivery companies have implemented new policies meant to protect workers and customers. Postmates and Instacart have unveiled “no-contact” food delivery, while DoorDash is letting users leave in-app instructions if they prefer orders left at the door.

Data from the website OpenTable showed a “severe reduction” in the number of online reservations, phone reservations and walk-ins this week.

In an attempt to avoid commission fees and create more hours for furloughed staff, several restaurants are forgoing delivery apps altogether, asking customers to phone in their orders and deploying restaurant employees to complete deliveries themselves.

Jennifer Feltham, co-owner of Sonoratown in downtown L.A., said her taqueria had never handled its own deliveries, but converting some staffers to delivery roles was an option she was exploring. “The [delivery] services take a chunk,” she said.

At Japanese sandwich counter Konbi in Echo Park, chef-owner Akira Akuto said he briefly considered partnering with a delivery app after the shutdown was implemented but was dismayed that most had no plans to alter their commissions. “We reached out to the companies to see if they were lowering their fees, and they said no,” Akuto said. “So we decided that we’re going to focus on pickup instead.”

Akuto also said that, despite what many customers may think, partnering with a delivery service was not as simple as flipping a switch. “You have to integrate with their software, their P.O.S. [point-of-sale] system, there are so many steps. It’s not an easy process.”

For now, Akuto recommends that customers who want to support dining establishments check first to see if they can place an order directly with the restaurant through phone or email.

“We’re all trying to adapt as fast as possible,” Akuto said. “At this point, no one is expecting to make money or even cover the bills. The name of the game is how can I lose as little money as possible.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.