‘Thank God for social media’: How TikTok cooking stars are defying the traditional career path

- Share via

It’s a typical COVID-19-era story for Los Angeles restaurant workers. In March of last year, 28-year-old line cook Brandon Skier lost his job when his restaurant closed after several unprofitable weeks under L.A. County’s shutdown. Skier had been working at Auburn, the celebrated tasting menu restaurant on Melrose Avenue, and has 10 years of experience that includes stints at Redbird and Providence. He spent the first two months of the shutdown hunting for work.

“All the restaurants that I would’ve applied to were closing,” Skier said. “I was just bored at that point. I missed being productive, I wanted to work with my hands and create stuff, I wanted to keep cooking.

“So, I went on TikTok like, ‘Hey, I cook. If I post a video, would anyone want to watch?’”

One year later, Skier has more than 1 million TikTok followers, brand deals with Hedley & Bennett aprons and Made In cookware, and a new vision for his career. As the heavily tattooed, hoodie-wearing @sad_papi, Skier shows viewers how to operate like a professional cook at home, whether he’s making a banana cream pie or properly caring for carbon-steel pans.

“I just stood behind a stove for the last 10 years and nobody cared,” said Skier, whose dream before the pandemic was to become a sous chef at a fine-dining restaurant. “I didn’t know that there was a living to be made doing this kind of stuff. I never thought I would be in the position where people would look up at me as a cook.”

Skier isn’t the only one whose culinary aspirations have changed since the virus decimated restaurants and boosted the popularity of TikTok, which has at least 100 million users in the U.S. There’s no one stopping a teenager from Indonesia or a grandmother in Nigeria from pressing “post.” And some of those who are contributing content, stars who have emerged organically, have amassed an astonishing number of followers.

Tway Nguyen was finishing culinary classes and planning to work in a restaurant or open a food truck before the coronavirus hit.

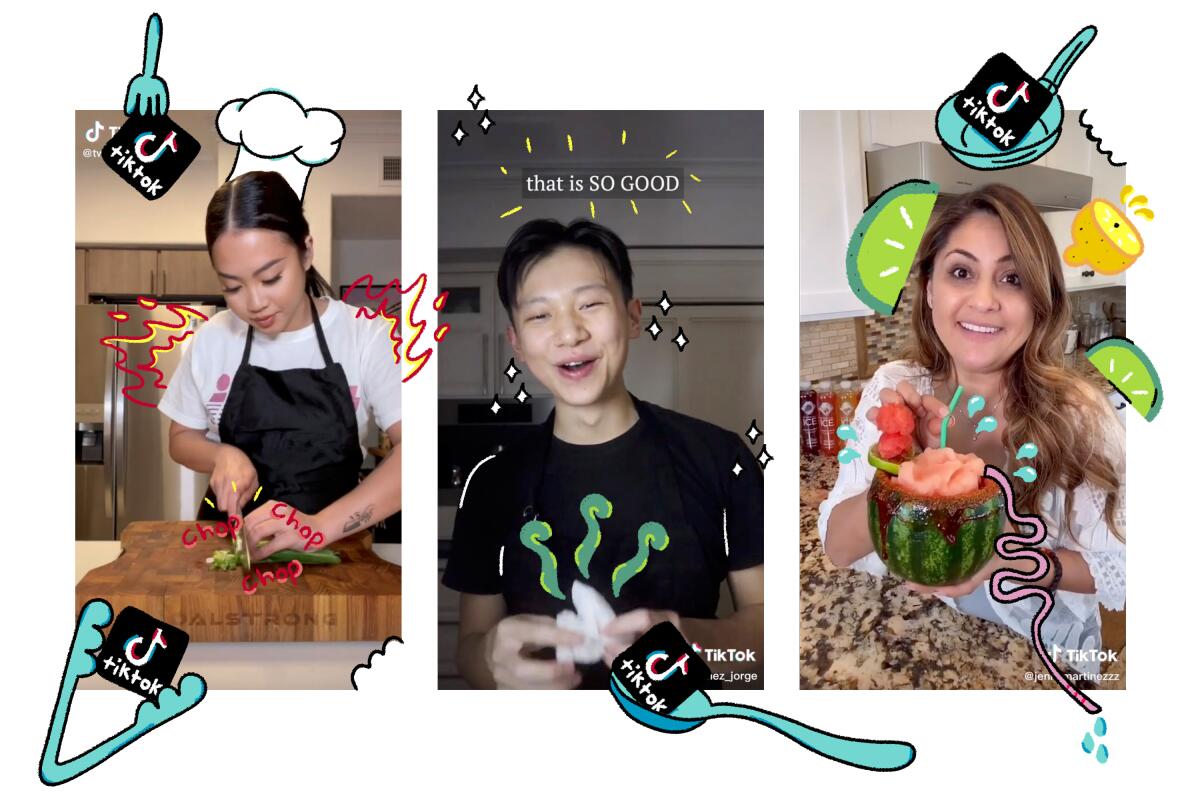

One morning in March of last year, she woke up and started cooking for her family as usual. Only this time, she decided to film it. One of her first cooking TikToks, a 30-second clip of her making fried rice with lap cheong in a T-shirt and messy bun, has 7 million views.

For Nguyen — who has since hired a business manager, started a recipe newsletter and begun designing @twaydabae merchandise — online stardom is the alternate path in food she never knew she wanted to pursue.

Of working at a Beverly Hills restaurant during her culinary training: “It was a nightmare, it was the worst experience of my life,” she said, laughing. “I felt like, ‘Why did I even go to culinary school?’ Working on that line was just so much pressure. Whenever I cook at home, that’s my happy place.”

Thanks to that fried rice video, Nguyen, who spent her childhood in the southern Vietnamese beach town Vung Tau before moving to L.A. with her family, can make a living by demonstrating dishes like canh chua (a sweet and sour soup with fish and tamarind) in bite-size videos from the comfort of her home kitchen. (She’s working on one-off sponsored videos for some brands, and some of her kitchen tools are provided by Dalstrong.)

“I just thought there was one path in culinary: You would work your way up to head chef,” said Nguyen, who has 526,300 followers. “Thank God for social media.

“Asian Americans, especially Vietnamese Americans, always tell me, ‘Hey, I live away from home, and your recipes make me remember all the good times and remember my mom,’” Nguyen said. “I kind of found my message and ultimate goal of keeping my culture alive through sharing recipes.”

While Nguyen has been able to educate viewers that Vietnamese cuisine “goes beyond pho or spring rolls or egg rolls,” 19-year-old UC Berkeley sophomore George Lee, known as @chez_jorge on TikTok, is helping to fill another gap in food media: vegan versions of Taiwanese staples, presented in English by a Taipei native.

Many of Lee’s videos start with sizzling garlic or soaking shiitake mushrooms and end in a plate of saucy noodles, crispy vegetables or bouncy dumplings. All of them include Lee’s smiling face and obvious enthusiasm for plant-based versions of things he grew up eating in Taiwan.

“I feel a sense of purpose when I make these videos and people tell me they love my recipes,” said Lee, who has 483,700 followers. “It’s helping the environment, and it’s teaching people how to live a more sustainable life without having to sacrifice tasty food.”

Lee studies molecular cell biology and works in an alternative-meats lab (when classes are held on campus) at Berkeley. He doesn’t expect to graduate for another two years, but his post-college plans are already taking shape; he’s in talks with cookbook publishers and hopes that if he pursues his own meat-alternative startup — to develop more convincing vegan versions of foods like pork belly and chicken — his audience will be interested.

“I like taking a kind of scientific approach to my cooking. I love to know why something works,” he said, excitedly explaining how you can cook eggplant to mimic eel and make tofu extra crispy by freezing and thawing it twice before cooking.

Like Skier and Nguyen, Lee has trained as a cook. (Lee attended Le Cordon Bleu and interned at Chez Panisse for a semester.) When starting out on TikTok, they all knew how to cook but had to teach themselves how to be content creators: What camera equipment to buy, which editing software to download, and how to use it all to make videos that people want to watch and save.

Skier, who rarely cooked at home while working as a line cook, “didn’t even have a decent cutting board” when he started posting to TikTok last year. A few months later, he outfitted his kitchen like a restaurant with hotel pans, squeeze bottles, magnetic knife holders and a sous vide machine. His tools also include a high-definition camera, tripod and Final Cut Pro software.

Sometimes food TikToks are about more than just a recipe. For creator Morgan Lynzi (@morganlynzi), they should tell a story and create a feeling.

In a chocolate cake video posted before Valentine’s Day, Lynzi moves as if dancing, drizzling vanilla extract into a mixing bowl and unveiling the cake from the oven in slow motion. As the camera cuts in tune with the music, she soothingly narrates not about measurements or temperatures but a lesson she learned from a past relationship: The best love comes from yourself, to yourself.

Born in the late 1990s and raised in the age of social media influencers, Generation Z is TikTok’s main user base and craves “authenticity,” Lynzi said. Instead of selling products in her videos, she talks about growth, identity and “the decadence of everyday life” while cooking foods she loves, from Jamaican sweet potato pudding to plantain pie. It’s all to promote the idea that “self-care is a practice, not a purchase.” Lynzi, who lives in Los Angeles County, has 84,600 followers.

“I think what this generation is looking for is content that has soul — even if that is a recipe or skincare or beauty, we have to feel that there is a human behind it who goes through the same emotions as anyone else,” Lynzi said.

On TikTok, “It’s not, ‘I’m here to put out this superficial image of myself that I want you all to aspire to.’ It’s like, ‘Here’s the real me and here’s what I’m going through, and I would love for you to hear about it so we can have empathy and compassion for each other.’”

Other TikTokers say they have also noticed a demand for the genuine. Jenny Martinez, a 47-year-old mother of four living in the L.A. area, acquired more than 2 million followers by posting simply shot videos of her preparing dishes from the Mexican recipes used by her parents, like spicy camarones a la diabla and calabacitas with pork carnitas.

She’s now a local superstar, sponsored by brands like Bounty, El Super and Weight Watchers, but the woman behind @jennymartinezzz has a full-time sales job and no formal culinary training. Her kids taught her how to use TikTok at the beginning of the pandemic.

“People like the rawness of what I record; they see me as a regular person and say, ‘You make it look so easy,’ ‘This is how my grandma used to do it,’ ‘I see your videos and I can smell home,’” Martinez said. “That’s what touches me.”

If you’ve seen a video of someone making birria within the last year, it’s quite possible it’s because Martinez helped get it trending on TikTok in February 2020. Now, home cooks are dipping quesatacos in their homemade birria consommé on weeknights, and the #birria hashtag has been viewed more than 500 million times.

For Martinez, this is confirmation that people use TikTok to learn. When she films trips to the supermarket, followers are eager to hear what brands she buys. When kids see her videos, they ask their parents to make her recipes for dinner. Martinez says she frequently receives videos of elementary schoolers enjoying her food and repeating her signature phrases, “Beautiful!” and “Listo!”

Lynzi agrees that TikTok can be a great learning tool. With Syrian, Jamaican, Indian, French and Black heritage, she said she grew up in L.A. surrounded by “a mini United Nations” but realizes that not everyone else did. Because TikTok’s algorithm allows users to see videos at random, she thinks the app could promote better cultural understanding.

“I don’t know that there are very many echo chambers on TikTok,” Lynzi said. “They’re like, ‘Today we’re gonna take you to Egypt, and then you’re gonna learn about molecular biology and you’re gonna learn how to make a Jamaican pineapple peel tea.’

“Being able to see so many people’s cultures readily in a normalized context — it’s so different and it’s so amazing.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.