Senators want stronger ‘claw back’ rules after Wells Fargo scandal

- Share via

When Wells Fargo & Co. last month revoked tens of millions of dollars in pay from its CEO and another executive, it relied on an in-house policy that allows the company to “claw back” some pay in cases of misconduct that harms the bank’s reputation.

Under new rules being considered by federal financial regulators, Wells Fargo would have to beef up that policy to allow — though not require — the bank to claw back even more kinds of pay, including some granted up to seven years earlier.

On Wednesday, 16 Senate Democrats asked financial regulators to further tighten the proposed rules by forcing Wells Fargo and other banks to claw back executive pay when such misconduct occurs.

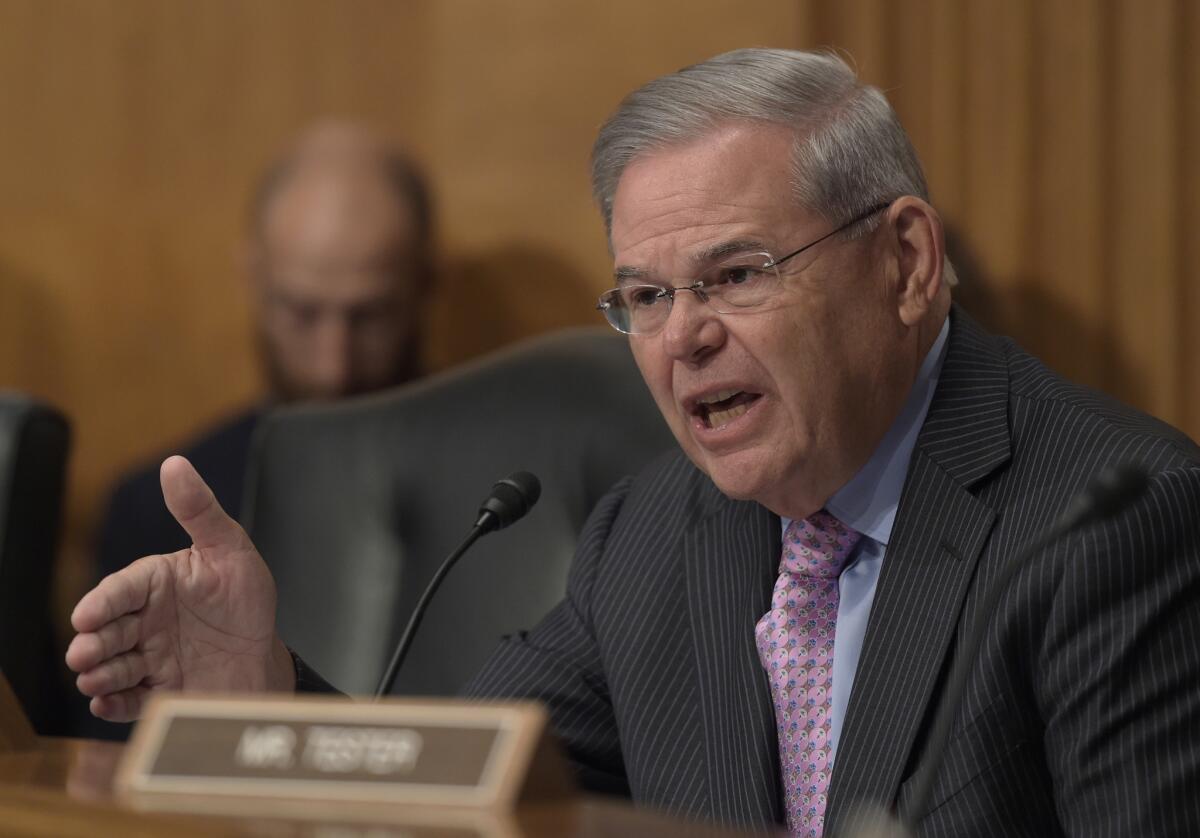

The senators, led by Robert Menendez of New Jersey, said allowing banks themselves to decide whether executives get to keep pay does not do enough to curtail the kind of wrongdoing uncovered at Wells Fargo, where thousands of employees created as many as 2 million accounts for customers without their authorization.

Executives knew about that practice for several years, prompting the San Francisco bank to revoke about $45 million in pay from now-retired Chief Executive John Stumpf and about $19 million from former retail bank chief Carrie Tolstedt, all of it in the form of stock and bonuses that had been promised but not yet paid out.

But the former executives did not give up pay or shares they received in the past, including in years when unauthorized accounts were being created. Stumpf left the bank with about $130 million in accrued stock and pension benefits that he will be able to keep. Tolstedt gets to keep about $80 million.

In their letter, sent to to the heads of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and other financial regulators, the senators said the new pay rules need to address the issues raised by the Wells Fargo case.

“Not only is this outrageous, allowing them to keep their bonuses sends a dangerous signal to other executives that you can oversee excessive risk-taking and widespread fraud and still get a multimillion-dollar payout,” said the letter, signed by Sen. Barbara Boxer of California and leading financial-industry critic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

“Therefore, we need tough rules that will ensure that executives who engage in this type of misconduct will have their bonuses clawed back so we can deter similar action in the future,” the letter said.

The proposed rules, which stem from the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act, have been in the works for years. They’ve been approved by most of the six regulatory agencies that must sign off on them, but it could be months before they are finalized. Even if they are ready this year, they would not take effect until 2018.

The rules aim to prevent banks and other Wall Street firms from taking too much risk by forcing them to structure incentive-compensation plans so that executives and other workers think about the long-term effects of what they’re doing, rather than any short-term benefits.

Among other changes, banks and other financial firms would have to pay out more of their incentive compensation over several years rather than upfront. They would also include the seven-year clawback provision.

The rules have been criticized by financial trade groups and institutions, including Wells Fargo, which in July sent regulators a letter calling for them to soften some parts of the proposal.

In an 11-page letter, Hope Hardison, the bank’s chief administrative officer, told regulators that Wells Fargo already has effective controls in place and that parts of the new rules would “be at odds with good performance management” and “appear punitive and not linked to risk-taking.”

For instance, Hardison said that it doesn’t make sense to be able to claw back pay for seven years given that most risks are realized within three to five years.

The bank declined to comment on Hardison’s letter, which was submitted well before Wells Fargo agreed on Sept. 8 to pay $185 million in penalties to federal regulators and the L.A. city attorney’s office over the unauthorized accounts.

Senators, though, said it often takes many years for misconduct to be discovered and pointed out that many penalties related to the financial crisis were not levied until about a decade after bad practices first took place.

Senators also criticized the proposed rules for not mandating clawbacks, noting that companies are often hesitant to revoke pay.

“A discretional clawback provision is not likely to have much of any deterrent effect against inappropriate risk-taking,” the senators wrote.

But making clawbacks mandatory could be difficult. For starters, it’s not clear that the section of Dodd-Frank at issue could justify a mandatory clawback provision, said UCLA law professor Steven Bank.

The section is supposed to discourage policies that incentivize too much risk-taking, not necessarily punish wrongdoing after the fact.

Beyond that, Bank said calling for clawbacks in cases of misconduct raises two big questions: What counts as misconduct and, perhaps more importantly, who decides whether misconduct has taken place? Is it the bank’s board or a financial regulator?

Bank said Wells Fargo was able to take some pay back even though there has been no formal finding of wrongdoing by Stumpf or Tolstedt. And though the bank settled with regulators, it has not admitted any wrongdoing.

“Wells Fargo’s policy allowed them to claw back without a formal legal finding. If it were mandatory, you could argue it’s out of the board’s hands,” Banks said. “I don’t know that we solve anything by making it mandatory.”

The senators’ letter came on the same day as the latest quarterly report from the federal watchdog set up to oversee the Treasury’s Troubled Asset Relief Program, which bailed out banks during the financial crisis. That report also included suggestions on how to rein in the kind of abuses uncovered at Wells Fargo.

Christy Goldsmith Romero, the special inspector general for TARP, said bank executives and other corporate bosses should be forced to certify every year that there is no criminal conduct or fraud going on in their companies.

“Wall Street CEOs and other high-level executives do not have an incentive to identify crime and civil fraud in their organization,” Goldsmith Romero wrote. “They can hide behind the idea that because their firm is so big, they cannot be expected to know everything that happens within it.”

Follow me: @jrkoren

UPDATES:

4:30 p.m.: This article was updated with details about Wells Fargo opposition to the new rules and comments from Steven Bank, a UCLA law professor.

This article was originally published at 12:20 p.m.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.