Gov. Brown says fixing delta water system important for entire state

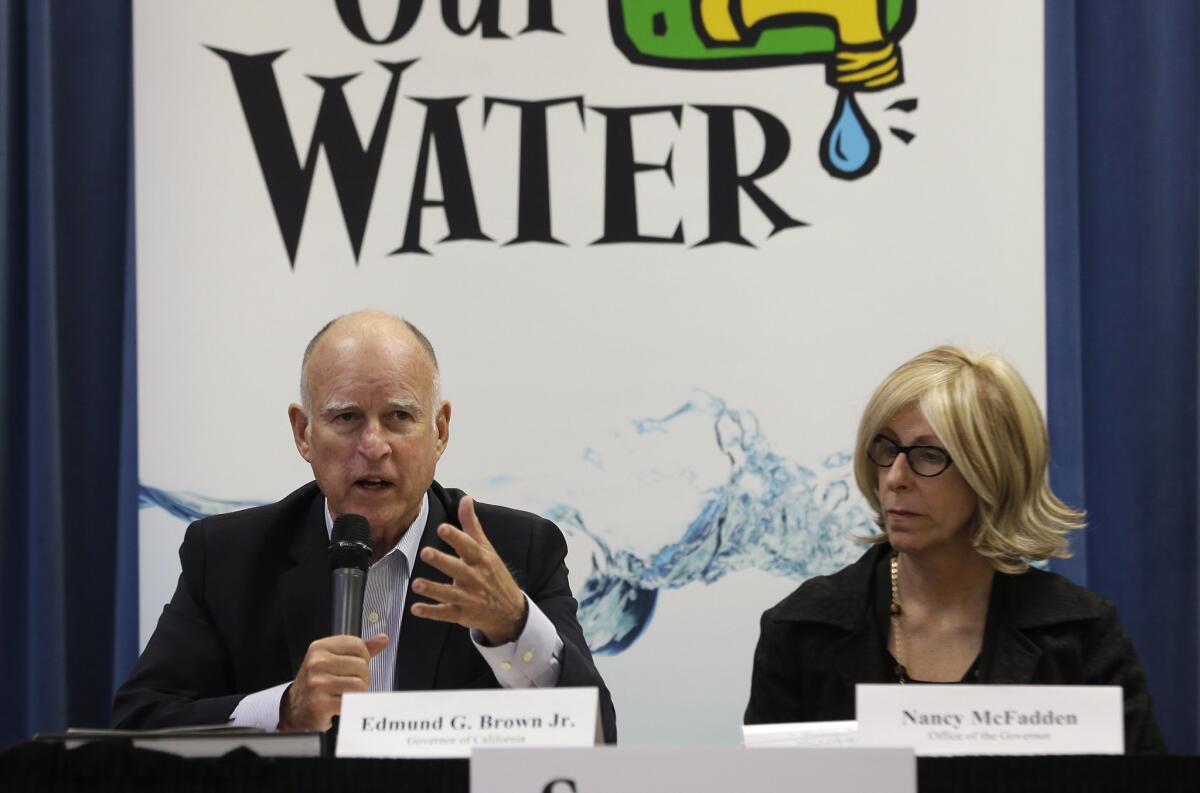

Gov. Jerry Brown, with Executive Secretary Nancy McFadden, talks to reporters at the end of a meeting on the drought last week.

- Share via

Gov. Jerry Brown called on California to support a plan to transform the heart of one of the state’s most important water systems, saying failure to take action on the delta could risk disaster for not only Southern California but the San Francisco Bay Area as well.

“It’s something that affects Los Angeles, that affects farmers … it affects all of Southern California … and it affects Silicon Valley,” the governor told the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California on Tuesday. “What’s there is a very vulnerable system.”

Many cities in California and the farmers of the San Joaquin Valley now get a big portion of their water from the delta, where the state’s two largest rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, meet.

Southern California gets water by turning on giant pumps that artificially force the San Joaquin River to flow backward, killing fish such as salmon and smelt, causing such great environmental damage that water deliveries to the region have been restricted. Parts of the Bay Area, such as Livermore and Silicon Valley, also rely on water from the delta, Brown said.

A possible solution now under review is building giant tunnels that would route water farther upstream from the water-rich Sacramento River around the delta, instead of through it.

That would ensure Southern California would retain access to fresh water from the Sacramento River even as rising sea levels push salty ocean water farther into San Francisco Bay and the delta.

Century-old levees in the delta could also collapse in an earthquake or bad storm and allow salt water to flow into freshwater areas.

The tunnel plan, though, has run into opposition from critics suspicious that it is merely a front that would allow Southern California to drain water from Northern California, even in dry years.

But Brown said the plan is important to Northern California, too. Livermore gets 80% of its water from the delta, and Silicon Valley gets 40%, he said.

“If we do nothing ... there will be a collapse, whether it be tomorrow, five years, 10 years, 20 years. It’s going to happen in the lifetime of the people in this room,” Brown said.

Brown said the plan would actually help store surplus water that California would get in wet years, which could then be transported down to Southern California and fill in empty reservoirs. Without the system, California would have to flush out excess freshwater to the Pacific Ocean during wet years.

“Think of this as an insurance policy. We’ve got to make sure that we can capture this water and convey it in a reliable, secure way,” Brown said. “It’s not water you’re going to take in a dry year. It’s water that would fall out to the ocean -- and not be used by anybody -- that could be captured.”

Doing nothing would risk the destruction of a key source of fresh water for the state, Brown said, adding that many officials and scientists have come to consensus on the tunnel plan as a solution.

“It’s not about Los Angeles, or the Sierras, or the Bay delta. Because it’s about California,” Brown said. “We have to rise to the occasion where we see the commonality that we are tied together. And the well-being of our state means we all work together.

“We are in a very unusual period in terms of our population growth, in terms of the power of our technologies that we are deploying, and in terms of the existential consequences that will ensue if wisdom doesn’t trump short-term expediency and narrow parochialisms.”

Brown said an engineered solution is crucial to fixing the problem, which has been known for decades but for which nothing has been done. Since European settlers came to California, “in our short time, we have wreaked havoc on the basic resources, the natural beauty, and natural habitat of California. But there’s no going back.

“We have engineered to an incredible, almost unimaginable degree, the water systems of the state, with dams and canals,” Brown said. “There is no way back to what it was when the native peoples were here.

“We have to go forward with even more sophisticated engineering, which will both supply the water we need, will protect habitat … and we’ll use this resource in a most elegant, efficient and productive and wise way that we can.”

The idea of using tunnels to carry water around the delta instead of through it is not new.

Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of the Metropolitan Water District, said San Francisco built a tunnel nearly a century ago to get water from the Hetch Hetchy Valley to the city without it mixing with delta water.

“People in Northern California go, ‘This is all about Southern California.’ And he’s going, ‘No.’ You get your water [from the delta]. So does Contra Costa County. So does Oakland. So does Silicon Valley,” Kightlinger said. “If the delta collapses, they will be drinking salt water.”

There are several Bay Area agencies that would fund the proposed tunnel system and would get water if it is built.

Brown’s meeting with the Metropolitan Water District comes as the governor has been touring the state to raise awareness of the drought. On Tuesday at 6 p.m., Brown is set to hold a conversation with Los Angeles Times Publisher Austin Beutner at USC about the California drought that will be aired live on latimes.com and KCET.org.

Last week, Brown spoke to Bay Area elected and water officials meeting at San Jose City Hall, saying he wanted to use the bully pulpit to persuade Californians to cut back on water use.

The governor has made the drought a huge priority for his administration.

Sign up for The Times’ new drought newsletter, Water and Power

On April 1, Brown stood on a brown field that would have normally been covered in snow and ordered cities and towns across California to cut water use 25% as part of a sweeping set of mandatory drought restrictions.

Since then, Brown has called for $10,000 fines for water wasters, directed his administration to expedite environmental reviews of some water projects and proposed accelerating spending to battle the ongoing drought.

In a $169-billion budget plan released in May, Brown proposed using $2.2 billion -- funded mostly by Proposition 1, a $7.5-billion bond measure for water projects approved last year by voters -- to prevent or alleviate groundwater contamination, recycle more water, safeguard drinking water in poor communities and fund other efforts.

Special coverage: More from The Times’ drought coverage

Brown’s response has been criticized by some who say the drought mandates go too easy on agriculture. The vast majority of Brown’s plan focuses on reducing urban water use -- such as water used on lawns, golf courses, parks and public medians -- which makes up less than 25% of Californians’ overall water use.

Brown and other top state water officials have said that farmers have shouldered their share of the burden. They say the 25% reduction in urban water use is attainable.

Last month, the State Water Resources Control Board assigned conservation targets to each of the state’s urban water suppliers, requiring cuts in consumption ranging from 8% to 36% compared with 2013 levels. Cities and water districts with the lowest per capita consumption during the summer of 2014 suffer the smallest cuts, while heavy users must cut the most.

The state water board can issue cease-and-desist orders to water suppliers for failure to meet conservation targets. Water agencies that violate those orders are subject to fines of as much as $10,000 a day.

Progress has been uneven. In April, Southland water users cut their consumption 8.7% versus the same month in 2013 — the poorest showing among the state’s hydrologic regions. Other regions of the state cut use as much as 37.5%.

Twitter: @ronlin @ByMattStevens

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.