Clinton says she’s talking to lots of economists, but progressives want names

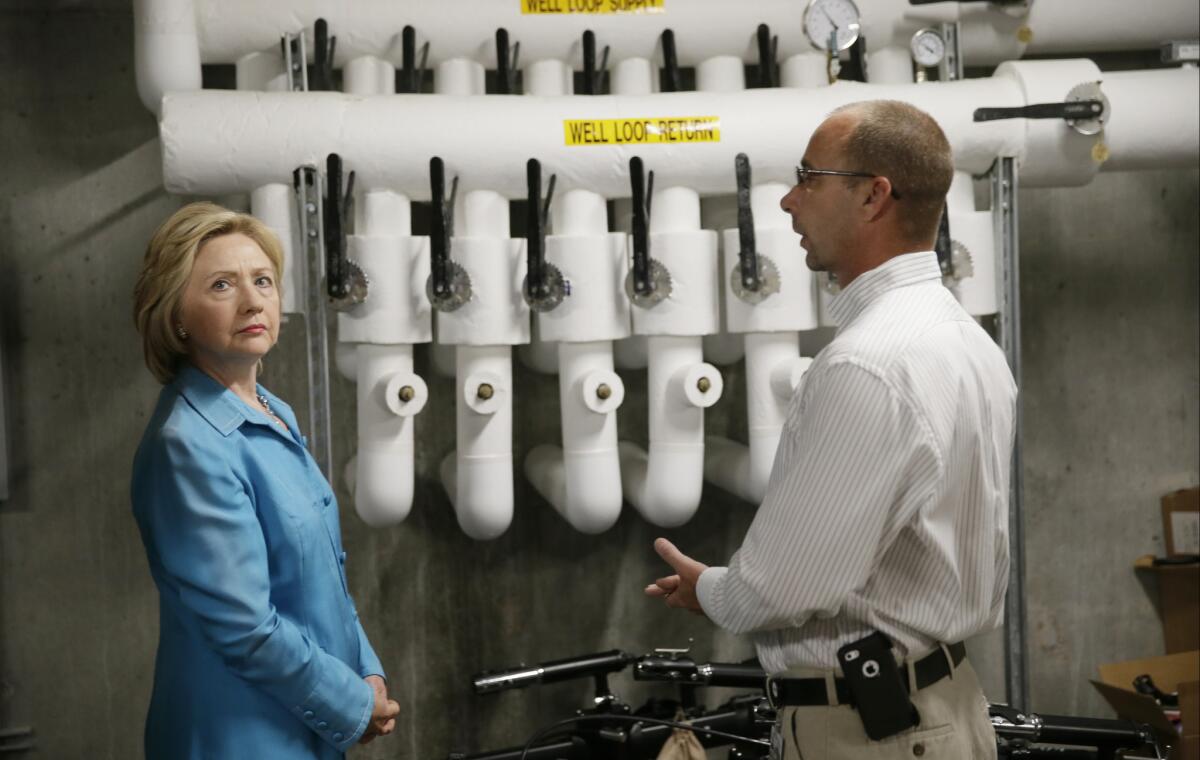

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton, shown touring the Des Moines Area Rapid Transit Central Station on Monday in Iowa, has pledged to keep Wall Street out of her inner circle if she wins the race for the White House. But progressives are skeptical.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Hillary Rodham Clinton is adamant that she is no friend of the fat cats, yet she can’t seem to shake the view held by a crucial swath of Democrats that if she gets to the White House, Wall Street insiders will be whispering in her ear.

The suspicions persist even as Clinton rails against an economy she says is rigged for the 1%, solicits advice from the left’s most prominent financial thinkers and rolls out an economic plan with a sharply populist tone. In a major campaign speech in New York on Friday, Clinton criticized a culture that she said prioritized short-term profits for a few over the long-term shared prosperity of the many.

“It is clear that the system is out of balance,” she said. “The deck is stacked in too many ways, and powerful pressures and incentives are pushing it even further out of balance.”

See the most-read stories this hour >>

What Clinton did not say is something some of the most influential union leaders and Democratic activists are looking to hear: that if she wins the presidency, she will lock Wall Street sympathizers out of not just the Oval Office, but also from serving in some of the most obscure undersecretary posts.

Clinton is under unprecedented pressure to preclude an entire class of individuals from advising her. Led by Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and prominent labor leaders, activists who feel betrayed by the clout of the financial sector in the administrations of President Obama and former President Bill Clinton are demanding that she prove that her time in the White House would be different. Clinton’s opponents in the Democratic primary have made the issue all the more uncomfortable by rolling out “revolving door” proposals intended to prevent Wall Street insiders from gliding in and out of government.

“There is no shortage of extremely talented people who would like to serve this country,” said former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, who served under Bill Clinton alongside advisors he described as “determined to do Wall Street’s bidding.” “If somebody does not want to make the financial sacrifice because they cannot get back into a hugely lucrative position right after, they are not the people who should be there in the first place.”

TRAIL GUIDE: Daily tour through the wilds of the 2016 presidential campaign >>

Reich says White House officials involved in setting financial policy should be banned from working in high finance for five years after they leave government.

More than 63,000 people have signed a petition sponsored by two progressive advocacy groups demanding candidates embrace such policies. Even more pressure is coming from Capitol Hill, where Warren is leading a crusade to block some of the current White House appointees to obscure financial posts. When Clinton appears before the executive council of the AFL-CIO this week seeking the union’s endorsement, its leaders will be drilling down on the people she intends to surround herself with.

“It is important to us,” said Larry Hanley, president of the Amalgamated Transit Union. “Obama came out and had a platform of hope and change and he did it in a generic enough way that all of us got to project what we wanted into his comments. Then he sent Larry Summers down to stick a pin in it.”

Summers, a friend of Clinton’s who served as her husband’s Treasury secretary and then as an architect of Obama’s economic plan, is repeatedly cited by labor leaders as someone they would like nowhere near the White House ever again. Hanley is still fuming over a congressional proposal to invest $2 billion in mass transit in the 2009 economic stimulus package that he blames Summers for scuttling.

“It was the most aggressively caveman, anti-worker, anti-minority position you could possibly take,” he said. Hanley was blunt about the lesson in it all for Hillary Clinton: “If you surround yourself with a bunch of Wall Street scumbags, you will have a bad outcome.”

Summers, who earned millions of dollars advising a hedge fund and delivering speeches to big Wall Street firms after leaving the Clinton administration, declined to be interviewed. He is keeping a low profile during the campaign, even as Clinton’s economic agenda appears heavy with his fingerprints. Like many Democrats, the economic views of the former Treasury secretary have lurched left lately, most visibly when he co-wrote a report for the Center for American Progress calling for a restructuring of the economy that shifts more of the nation’s wealth downward.

Still, many progressives have not warmed to him.

“Almost everyone is wary of Summers,” said Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic Policy Research, a liberal think tank. When the Clinton campaign published a list of some of the thinkers who helped shape Clinton’s policy on the economy, Summers was not mentioned.

The campaign is highlighting all of the advice Clinton is taking from labor favorites such as Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University, a Nobel Prize winner, and Richard Freeman of Harvard, as well as others critical of Wall Street, but acknowledges Clinton is also talking to unnamed others.

This month, Clinton sought to assuage concerns that Wall Street would have outsized influence in a Hillary Clinton administration by vowing, “I will appoint and empower regulators who understand that ‘too big to fail’ is still too big a problem.” Still, the pressure to be more specific mounts.

Baker recalled how Bill Clinton made many of the same assurances and pleased progressives by seeking counsel from celebrated liberal academics and appointing Reich to his cabinet. But it quickly became clear that it was then-Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, a former chairman of Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, who would guide economic policy.

“If anyone on the progressive side was ever naïve about this,” Baker said, “they are not anymore.”

For more campaign coverage, follow @evanhalper

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.