Column: A memoir unlike any you’ve read: A young woman’s inspiring struggle with her invisible killer

- Share via

Mallory Smith was a toddler in 1995 when doctors finally diagnosed her persistent cough and runny nose: cystic fibrosis. Life expectancy with the disease at the time was between 25 and 30 years.

Upon hearing the news, her mother collapsed.

“Our new normal: a child with an expiration date,” said Diane Shader Smith, as we sat in the dining room of her home on the south side of Beverly Hills on Wednesday talking about the life and death of her remarkable daughter.

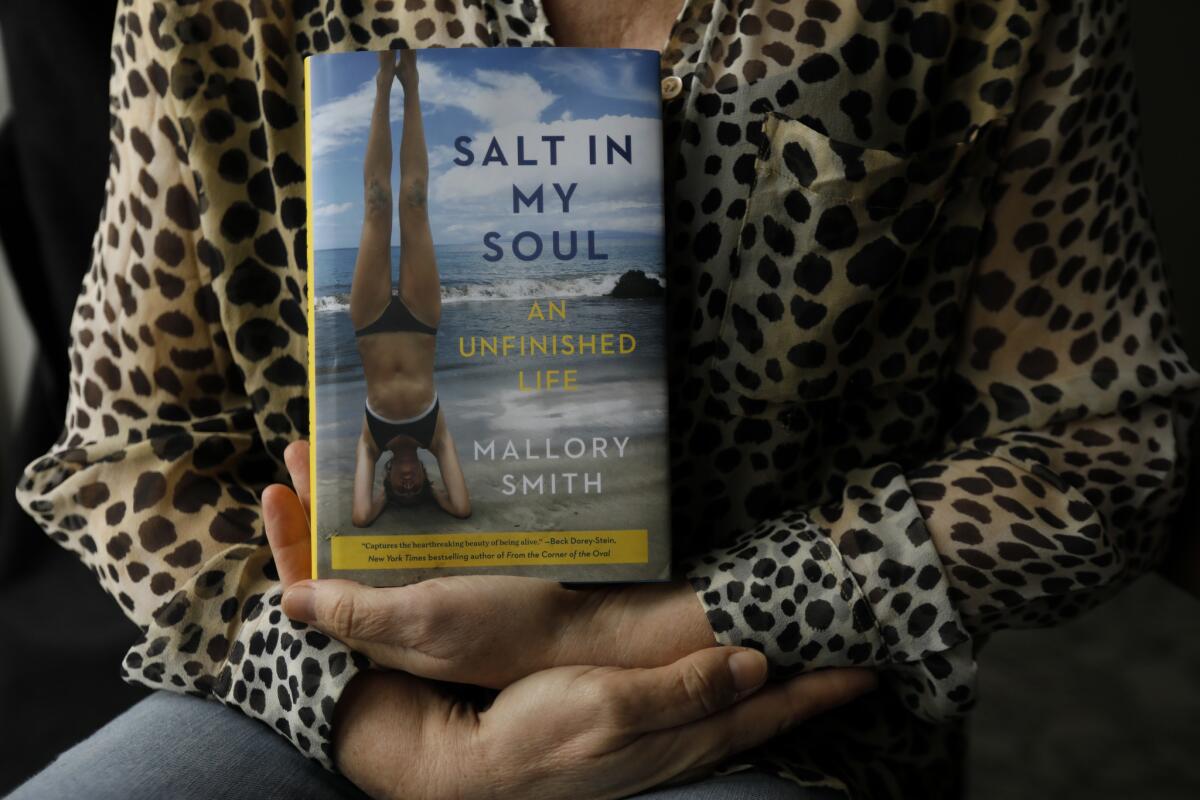

I never met Mallory; she died at age 25 in 2017. But I have come to admire her through her posthumous memoir, “Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life,” published this month by Penguin Random House. It is based on journals she began writing at 15 and allowed her mother to read only after she died.

Cystic fibrosis is a dreadful genetic disease that, put very simply, produces sticky mucus in the lungs that makes it hard to breathe and easy to contract deadly bacterial infections. Every year brings promising medical advances, but there is still no cure.

Treating CF can be all-consuming. Every day until Mallory was big enough to wear a compression vest, her dad, Mark Smith, had to paddle her chest and back to loosen the mucus in her lungs, so she could cough it up. At least twice a day, she covered her nose and mouth with a mask and breathed in steam and antibiotics.

She became adept at hiding to try to avoid her treatments, prompting her mother to publish a children’s book, “Mallory’s 65 Roses,” to explain what happens to a kid with CF. (“65 roses” is how some children are taught to pronounce “cystic fibrosis.”)

When Mallory was 9, she decided she’d had enough. No more treatments. She wanted to be like other kids. Her father sat her down, brutal honesty his only option. If you don’t do your treatments, he told her, you will die.

She recounted the moment years later in her journal:

“I burst into tears, leapt up from the table, and ran to my room, slamming the door behind me,” Mallory wrote when she was 21. “I hated them. I hated that keeping myself alive was such an inconvenience, I hated that my dad forced me to face my own mortality and I hated that they were right.”

At Mallory’s memorial, Mark, 62, recounted that story as one of the most wrenching episodes of her childhood.

When Mallory was 13, the family received awful news: She had contracted an antibiotic-resistant superbug, B cepacia, for which there was no treatment. “My disease,” she wrote, “has proven itself to be a cunning and unpredictable enemy, attacking from the inside like a Trojan horse.”

And yet, for 12 more years, Mallory not only lived, she thrived.

Unlike many kids with CF, who are small and sickly, she grew to 6 feet and was a standout athlete. She played three varsity sports at Beverly Hills High School — including water polo. She was a straight A student, and was chosen prom queen.

She became an avid surfer, spending as much time as possible in the salt water, which restored her spirit and, she believed, her health. An imbalance of salt in the body’s cells is an integral part of cystic fibrosis. “If you kiss or lick the skin of a CF-er, you’ll get a first-hand taste, literally, of how fundamental salt is to the disease,” she wrote. “I feel as if there’s salt in my soul.”

::

During her senior year in high school, Mallory had her first really terrifying medical encounter with CF. She had been losing lung function and was admitted to the hospital at UCLA. There, she underwent a procedure to remove as much mucus from her lungs as possible. The doctor nicked a tiny airway in her lung that allowed the B cepacia to invade her bloodstream:

“I woke up from the bronchoscopy in a disoriented and feverish sepsis. Four nurses held me down on the bed as my entire body convulsed violently and erratically, while my fever climbed from 103 to 104, then to 105, up to 106. More nurses arrived to cover my face and limbs with ice packs. I remember the pain, confusion and disorientation, the sea of faces towering over me trying to soothe me, the nausea, the feeling of bathing in fire and the terror of feeling like I was sitting off to the side, watching my body thrash and writhe without having any ability to stop it. …This was the first time CF shook me by the shoulders and made me look it in the eye to see it for what it really was.”

::

She went off to Stanford University, where the renowned campus hospital became her second home. She spent many weeks tethered to oxygen tanks and IV poles, taking countless medications, suffering from bloody coughing spasms, spiking fevers, gallstones, fungal infections and relentless gastrointestinal distress, severe pain and depression.

She majored in human biology and graduated on time, Phi Beta Kappa.

She moved to San Francisco, became a radio producer and freelance writer and editor specializing in environmental issues, social justice and health. While she awaited a double lung transplant, she launched a social media campaign, Lunges4Lungs, to raise money for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Through it all, she kept her journal.

She wrote in detail about her treatments and hospital stays, and about her frustrations, her deepening friendships, her romantic life, the intensity of her family’s love, battles with teaching assistants who didn’t understand why she had to miss class, her rage at callous health insurers, the transcendent intimacy she developed with her favorite doctors and the strangeness of appearing to be perfectly healthy when in fact she was terribly sick.

“It’s just so freaking HARD to figure out how to live because the docs always say not to let CF hold you back,” she wrote when she was 19. “I can’t plan things that other people plan. Like weekend getaways. I can’t plan to party and still do well in school. To travel to third-world countries and do something of significance. To go camping. To get married and have kids.”

In September 2017, after many false starts, she received a double lung transplant at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. At first, the transplant seemed successful, but soon Mallory’s new lungs were being overtaken by the superbug that had plagued her for 12 years.

As her condition worsened, scientists contacted by her father, a real estate lawyer, had begun a frantic worldwide search for a virus — known as a “phage” — that might have been able to kill the superbug. By the time her doctors were able to find the phage and inject it into her lungs, it was too late.

An autopsy determined, however, that the treatment had appeared to be working.

Mallory’s case has reignited interest in phage therapy. Since her death, two people with cystic fibrosis have been treated with phage therapy and gone on to have lung transplants.

::

The day of Mallory’s memorial, Diane opened up the electronic journal that Mallory had kept secret for 10 years. It was 2,500 pages long. Mallory wanted it edited and published, and she trusted only her mother to read it raw.

“I spent two to three hours a day holed up in my room laughing and crying while I read it,” Diane said. “My husband needed to see a grief counselor after six months, but this was my grieving process.”

Very quickly, Diane, a veteran publicist, understood she had a book on her hands, one that could inspire people facing impossible situations, that could help medical professionals better understand and deal with their patients, and raise money for cystic fibrosis research.

She found an editor and then a publisher, who gave her a healthy six-figure advance, none of which she will keep.

She already has more than 60 talks planned around the country to promote the book — at hospitals, universities, law schools, medical schools, high schools, tech companies and the New York Public Library. The book’s official launch is scheduled for March 17 at the Beverly Hills Education Foundation. In February, filmmakers Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick, who made “The Hunting Ground” and “The Invisible War,” began producing a documentary based on Mallory’s life.

“I don’t want people to think it’s a sad book and not want to read it,” Diane, 59, told me.

It is heart-wrenching — you already know the story has a tragic ending — but “Salt in my Soul” is so much more than a journey of illness and mortality.

Mallory’s writing blossoms from the precocious philosophizing of a driven teenager grappling with a serious disease into the exquisitely nuanced chronicle of a terrified but hopeful young woman whose life was beginning and ending, all at once.

“I have a strong urge,” Mallory wrote, “to write something that will change people. I want to create a piece so moving that people are in disbelief. And I want it to be like handing people a pair of glasses, giving them a way of seeing something they didn’t even realize they weren’t seeing.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.