Aggressive nonnative mosquitoes spreading across state carry disease risk

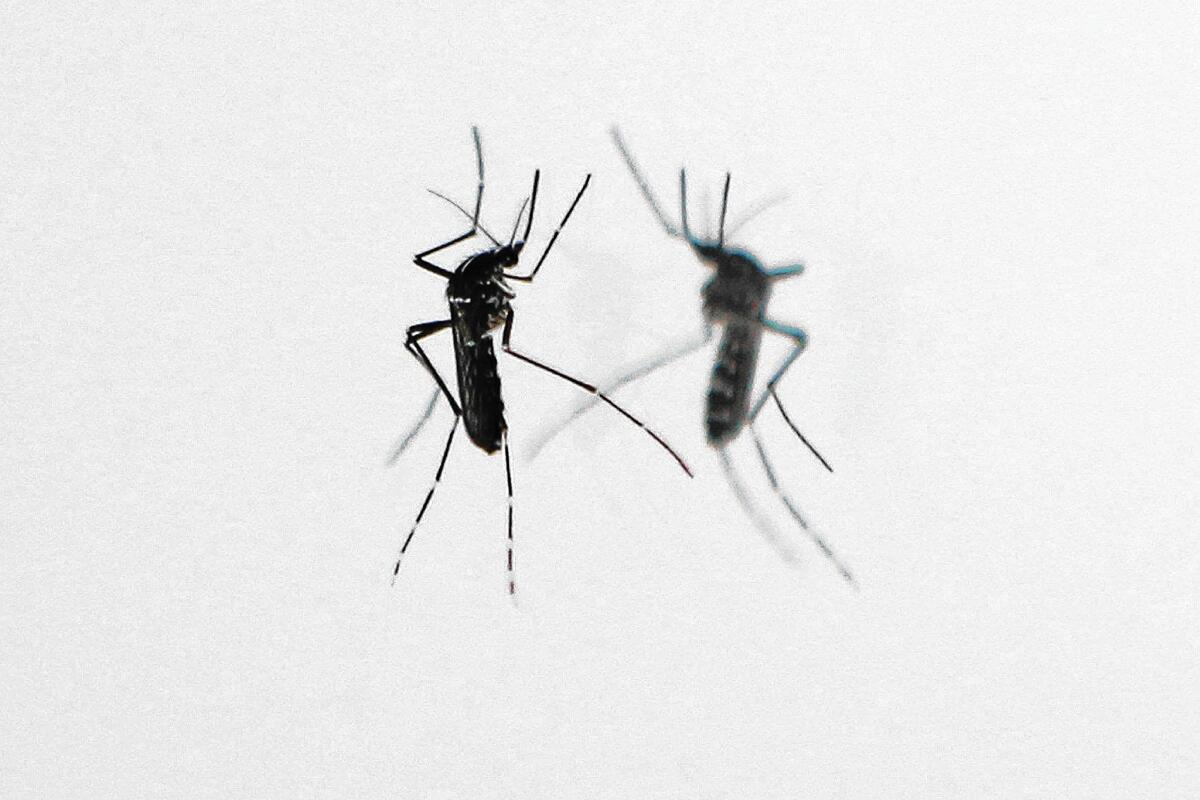

The Asian tiger mosquito, a nonnative species, bites in the daytime. Unlike native varieties, this mosquito can carry serious diseases.

- Share via

It has the makings of a science-fiction film: the threat of deadly disease, a metropolis oblivious to the impending danger and, of course, extraordinarily hostile insects.

That’s the scenario California health officials say they’re facing as they track the arrival of nonnative mosquitoes that can carry infectious diseases.

The insects are quickly spreading across Southern California — aided by the statewide drought — and have the potential to transmit dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever, all of which kill thousands of people around the world each year.

“It’s such an enormous problem,” said Kelly Middleton, director of community affairs for the Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control District, a public entity charged with managing mosquitoes and preventing disease transmission over a 1,340-square-mile region from Los Angeles to Long Beach to Diamond Bar.

So far, no one has become infected by these diseases in California; in fact, health officials say they are more immediately concerned with keeping down the number of West Nile virus cases, which are also mosquito-borne. But Middleton and her colleagues fear that it’s only a matter of time before the new diseases begin to spread.

About half the size of normal mosquitoes and with black-and-white stripes, the Asian tiger mosquito and the yellow fever mosquito—Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti, respectively—are unusually aggressive. Unlike mosquitoes more common to California that usually come out in the evening, these mosquitoes bite during the daytime. They can’t be easily swatted away and readily follow people into buildings or their cars.

These mosquitoes, neither of which are naturally found in North America, have shown up in California before but haven’t stuck around in the way they are now, experts say.

Experts think the current infestation in L.A. County started in 2011 in El Monte . The mosquitoes are believed to have been transported from Southeast Asia in shipments of bamboo plants.

The insects stayed mostly concentrated in the San Gabriel Valley. But this year, the mosquitoes have spread westward into the city of L.A.—they were recently found in Silver Lake —as well as east to Riverside and Montclair in San Bernardino County. They’ve now been detected in Montebello and Pico Rivera as well as Anaheim and Mission Viejo.

In total, they’ve been found in 12 of the state’s 58 counties, officials say.

Is that rapid spread due to the unusually dry, hot weather this year? “That’s the million-dollar question for us,” Middleton said.

Mosquitoes reproduce faster in hot weather, experts say.

“The climate in 2015 appears optimal for Aedes to expand,” said Kenn Fujioka, manager of the San Gabriel Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District, at a recent state legislative committee meeting.

Fujioka pointed out that the average minimum temperature in L.A. has been higher for most months in 2015 compared with the same months in 2011 and 2001.

Mosquitoes like humidity, Middleton explained, and these higher temperatures cause more evaporation in landscaped areas, which “produces an ideal microclimate” for the bugs.

“Some yards are just perfect little habitats for the mosquitoes,” she said. The insects need water to breed, but can do so in pools as small as that collected in a bottle cap, or in droplets of water stuck between leaves of plants.

And though counterintuitive, California’s ongoing drought might actually be making the problem worse.

When it doesn’t rain, people water their lawns more, leaving behind excess water for bugs to hatch their eggs in. Rain also has a flushing effect, which helps clear out bugs and eggs. “So a big rain year actually helps,” Fujioka said.

The switch to drought-tolerant landscapes that many Angelenos are making should help somewhat, Middleton said; those yards tend to collect less water and have fewer shaded areas that mosquitoes enjoy.

For now, Middleton’s team has been going door-to-door in infested areas searching for standing water and eggs. Even if there’s no water, the eggs can last for up to two years until there’s a water source.

“These mosquitoes are just terribly successful, and do very well in the environments that we provide them in urban areas,” she said.

Although the mosquito infestation hasn’t caused any cases of chikungunya or dengue in California, the state has seen 129 chikungunya and 73 dengue infections this year—all involving people who were infected abroad and then came here and were diagnosed, officials say.

The question is not if, but when, locally acquired cases will occur.

— Kenn Fujioka, manager of the San Gabriel Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District

“The question is not if, but when, locally acquired cases will occur,” Fujioka said. There’s no vaccine or treatment for chikungunya, which causes fevers and severe joint pain, or dengue, which causes severe headaches, fevers and pain. Both can be fatal.

The diseases could start spreading locally if a traveler infected abroad returns home and is bitten by a mosquito here. That insect could then carry the disease and bite and infect more people.

“The current risk is very low, but certainly not zero,” said Dr. Vicki Kramer, chief of the California Department of Public Health’s Vector-Borne Disease Section. The possibility of contracting yellow fever, which the bugs can also transmit, is essentially nil, she said, as there has been one imported case of the disease in California in the past 10 years.

Dr. Laurene Mascola, chief of the acute communicable disease control program for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, said physicians have been notifed to look for symptoms of the diseases and ask sick patients about recent travels. Taking travel histories has become more important, she said, because of international outbreaks of Ebola and Middle East respiratory syndrome, known as MERS.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

However, Mascola said the risk of foreign diseases shouldn’t overshadow bigger existing threats in L.A. County.

For dengue or chikungunya to spread locally, mosquitoes would have to bite infected patients during the five-day period when the virus is circulating in their blood, she said. If the patients were bitten abroad, there’s a small chance that they’d be back in L.A. County while the virus remains in their blood, and an even smaller chance that they’d be outside to be bitten, she said.

“You can see how that scenario would be really unlikely,” Mascola said. “The thing that people do need to worry about is what we do have, which is West Nile virus.”

This year in California, there have been 421 cases of West Nile including 81 in Los Angeles County and 39 in Orange County. That’s a big drop from the 801 cases last year, but higher than the most recent five-year average, she said.

“The bottom line… is just to avoid all mosquitoes,” Mascola said.

Follow @skarlamangla for more health news.

ALSO

Number of cases grows in Bay Area shigella outbreak

First public test of earthquake alert system rolls out at L.A. school

Why you shouldn’t wear those green contact lenses with your Halloween costume

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.