Here’s why George Soros, liberal groups are spending big to help decide who’s your next D.A.

- Share via

In most district attorney elections, the campaign playbook is clear: Win over the local cops and talk tough on crime.

But in California this year, the strategy is being turned on its head.

For the record:

3:00 p.m. May 29, 2018An earlier version of this story misspelled Kaitlyn Krieger’s first name as Katelyn. Also, among other contested races, it erroneously included Fresno County. The Fresno County district attorney is running unopposed. In addition, the story was updated to include that a George Soros foundation is among the funders of the Marshall Project.

Wealthy donors are spending millions of dollars to back would-be prosecutors who want to reduce incarceration, crack down on police misconduct and revamp a bail system they contend unfairly imprisons poor people before trial.

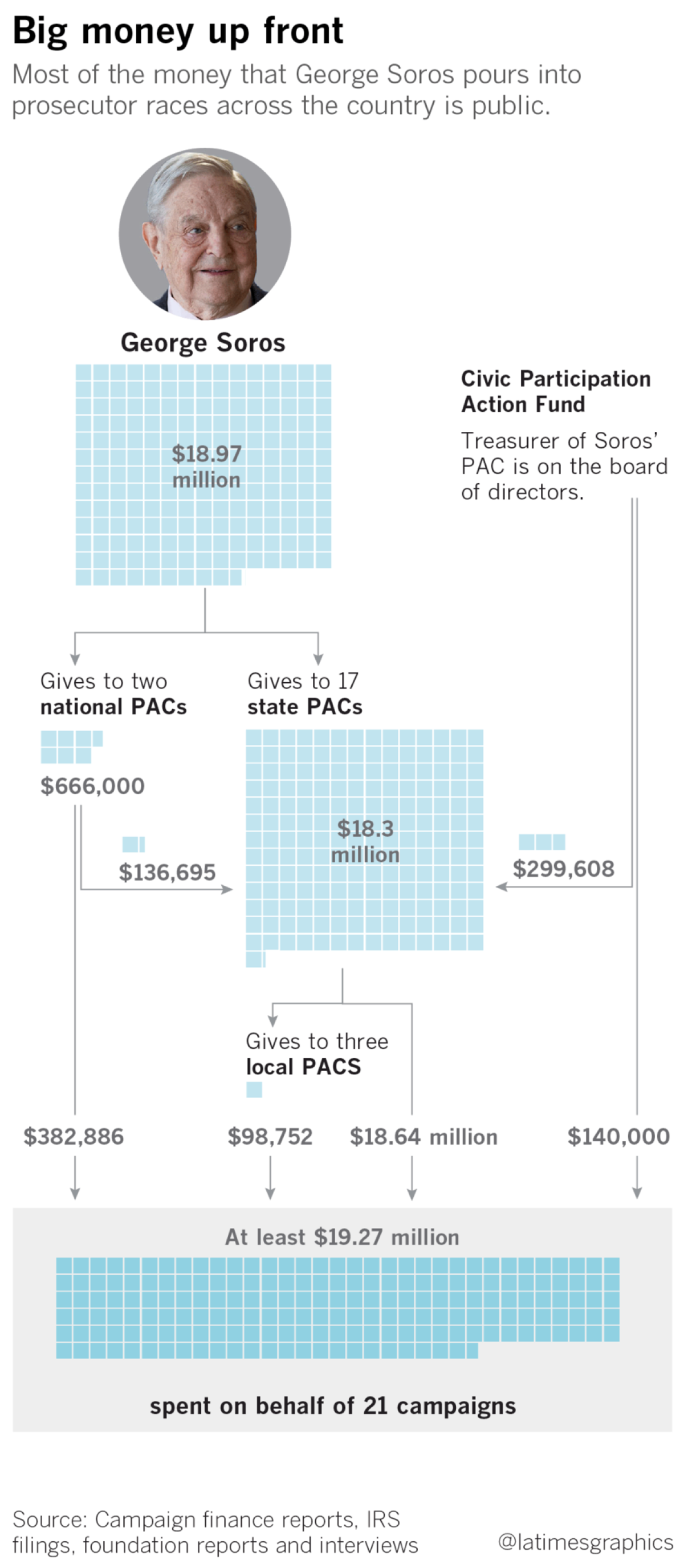

The effort is part of a years-long campaign by liberal groups to reshape the nation’s criminal justice system. New York billionaire George Soros headlines a consortium of private funders, the American Civil Liberties Union and other social justice groups and Democratic activists targeting four of the 56 district attorney positions up for election on June 5. Five other California candidates are receiving lesser support.

The cash infusion in the nonpartisan elections turns underdog challengers into contenders for one of the most powerful positions in local justice systems, roiling conventional law-and-order politics.

For years, district attorney races “tended to focus on character issues rather than policies.... So it’s really quite a change,” said Stanford law professor David Sklansky, a former federal prosecutor.

In San Diego County, the groups back a deputy public defender who spent her legal career trying to keep the accused out of jail, not lock them up. In Sacramento and Alameda counties, they finance candidates taking on entrenched incumbents. And in Contra Costa County, they support a former judge appointed as district attorney last year who faces an election challenge from a career prosecutor.

The challengers have matched or surpassed the millions of dollars — mostly from police, prosecutors and local business — flowing to incumbents unaccustomed to such organized liberal opposition.

But the coordination between big money and advocacy groups that don’t have to reveal their funding sources is largely out of public view.

The campaign has alarmed some law-and-order prosecutors, who warn that discretion over which laws to enforce and how has its limits.

“These people who want to create their own social policy are not worthy of the office,” said former Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley. “If they win in San Diego or Sacramento, L.A. is next.”

Many of the players funding liberal candidates joined forces in California four years ago to pass Proposition 47, which turned drug use and most theft convictions from felonies to misdemeanors. In funding local D.A. campaigns, activists hope to secure many of the sentencing and bail policies they have struggled to realize through laws or ballot initiatives.

The effect of Proposition 47 and other recent sentencing reductions is highly contested. Opponents say the changes caused a rise in crime, but proponents dispute the claim.

Where law-and-order campaigns appeal to fear, the new strategy targets anger.

One issue that has caught fire is police shootings.

“It’s really coming from this Black Lives Matter moment of police accountability,” said Margaret Dooley-Sammuli, criminal justice and drug policy director for the ACLU of California.

In Sacramento County, where liberal activists are embedded directly in the insurgent campaign of Noah Phillips, the deputy prosecutor is attacking his boss’ record of having never charged a police officer who shot a civilian.

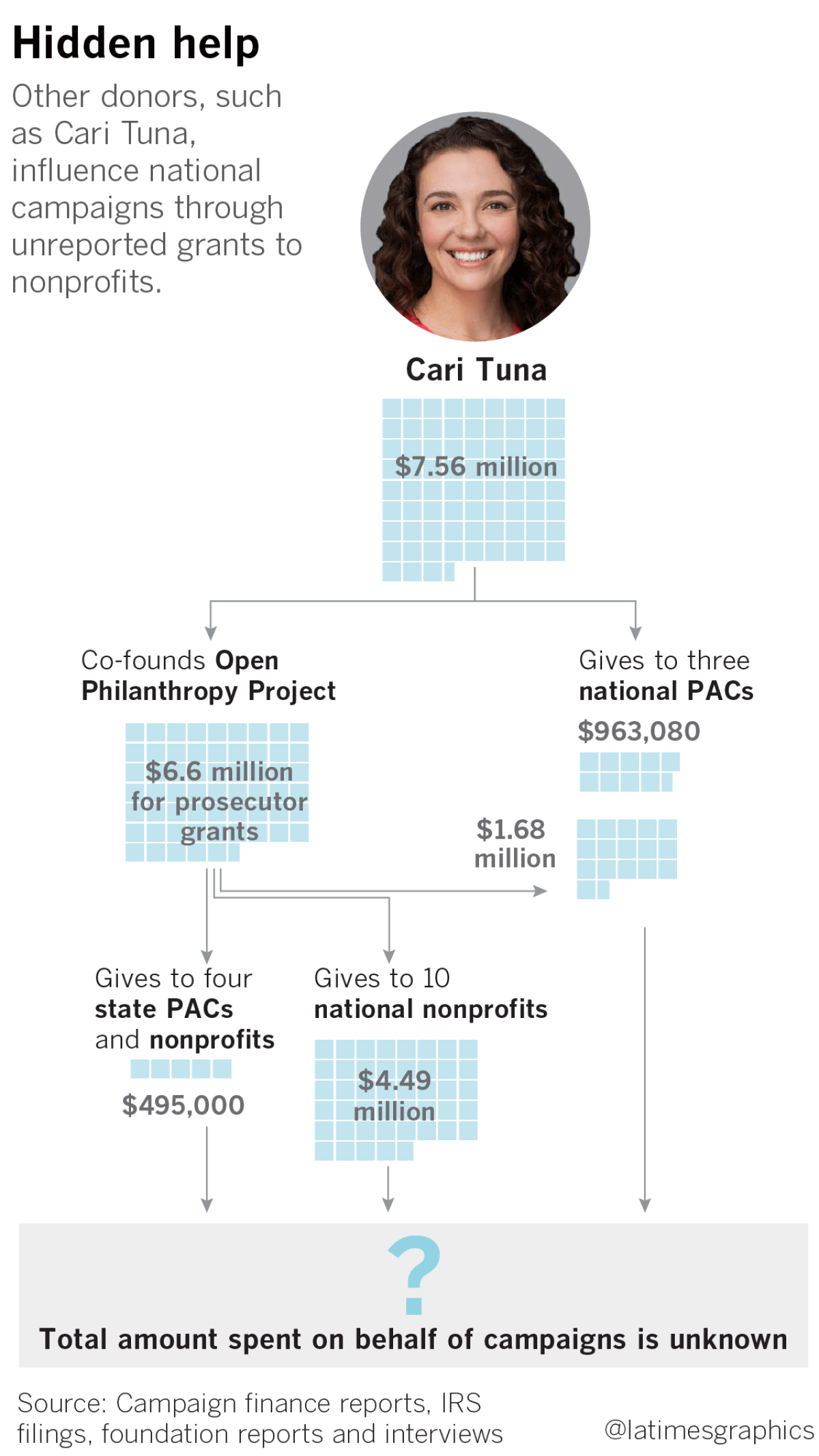

Phillips credits Soros’ team for scripting and paying for his television ad. Fundraising help came from a senior advisor to Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign, now at the helm of Real Justice, a political action committee with a mission to “fix our broken justice system” that is underwritten by Cari Tuna, the wife of Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. Other national advocates and philanthropists provide writing services and media coaching.

At the same time, Black Lives Matter activists were holding near-daily protests on the doorstep of Phillips’ opponent, career prosecutor Anne Marie Schubert. They demanded Schubert press charges against officers who earlier this year, searching for a burglary suspect, shot and killed an unarmed black man named Stephon Clark. To keep demonstrators at a distance, Schubert surrounded her office with a 10-foot fence.

Phillips has directly appealed to those in the African American community enraged by Clark’s death by dispensing leaflets at a memorial rally and through a Soros-produced TV ad that dwells on the face of a black boy beneath a hooded sweatshirt.

Schubert’s ads tout her role in the recent arrest of a man suspected of being the Golden State Killer, who terrorized Sacramento’s white suburbs four decades ago.

Each candidate is backed by about $1.1 million. Schubert, a leader in support of a proposed ballot measure that would toughen sentencing laws, draws most of her contributions from line-level prosecutors, the business community and police unions. Half of Phillips’ money is from Soros.

In San Diego, the county’s limit of $800 for individual contributions forces campaigners to work independently of their favored candidate, Geneviéve Jones-Wright.

Soros has supplied more than $1.5 million to a political action committee to promote the deputy public defender waging a longshot bid for D.A. National liberal organizations have joined the fight for Jones-Wright, as have wealthy Silicon Valley donors.

Decrying policies that are “criminalizing poverty,” Jones-Wright promises to create a police misconduct unit, stop seeking cash bail in low-level cases and end prosecuting “quality of life” offenses, such as sleeping on the sidewalk or loitering, which she says unfairly target the homeless.

The incumbent, career prosecutor Summer Stephan, favors more moderate changes and calls Jones-Wright “anti-prosecutor.” Stephan touts her work on sex-crime and human-trafficking prosecutions. Much of the $1.1 million backing her comes from police unions and prosecutors.

The grenades her campaign launches are aimed at Soros as much as at her opponent. When Soros’ first TV ads hit San Diego airwaves, Stephan’s campaign released ThreatToSanDiego.com, a website declaring public safety under attack. It carries a picture of Soros superimposed over masked, black-clad street demonstrators. In Sacramento this week, Schubert launched an almost identical website.

Jones-Wright rejects descriptions of her funding as an outside threat by groups trying to buy a national agenda, one county at a time. Soros’ money, she said, gives a voice to poor and minority communities often ignored in prosecutor races.

“I love it!” she told lawyers at a recent fundraiser. “If he didn’t take an interest in this campaign, it would be an even more uneven playing field.”

Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy O’Malley has expressed surprise that she’s a Soros target. The registered Democrat showcases endorsements not only from police leaders but also Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), organized labor and Democratic clubs.

Her opponent, civil rights lawyer Pamela Price, criticizes O’Malley’s ties with law enforcement, including political donations from police unions. Mailers sent by Soros’ PAC condemn “racist” stop-and-frisk policies and promise Price would end them.

Just to the north, liberal funders throw their support behind Diana Becton, a longtime judge recently appointed district attorney of Contra Costa County when her predecessor resigned amid a political corruption scandal. A veteran prosecutor hoping to unseat Becton seized on her financial support from “billionaires who apparently think Contra Costa’s public safety is for sale.”

Five more challengers in Marin, Riverside, San Bernardino, Stanislaus and Yolo counties are getting smaller donations from some liberal donors.

At stake is ensuring that prosecutors aren’t out of touch with the communities they represent, said Shaun King, co-founder of the Real Justice PAC.

“The district attorneys in our country don’t represent the true diversity, the broad cross-section of views of our country,” King said. “Less than 1% are women of color, which is a crazy number.… People who are running for the office of district attorney are prosecuting people they don’t know. They’ve never been to a picnic with them, never sat in a pew with them.”

Soros, whose spending as of this week in California topped $2.7 million, is the most visible part of the national movement to sway county prosecutor races. Since 2014, he has spent more than $16 million in 17 county races in other states. His favored candidates won in 13.

One of them, Philadelphia Dist. Atty. Larry Krasner, fired 31 prosecutors during his first week on the job in January. Calling for an end to “mass incarceration,” Krasner also ordered the rest of his office to stop prosecuting marijuana possession, steer more defendants toward diversion programs and announce at sentencing hearings how much a prison term would cost taxpayers.

After her 2016 victory in Houston, Kim Ogg announced she would no longer prosecute the possession of small amounts of marijuana. In Chicago, the Soros-backed candidate stopped filing felony theft charges for property worth less than $1,000.

The changes have outraged police and prosecutor associations. The head of the union for Los Angeles County prosecutors recently issued a statewide call for donations to counter Soros’ money in San Diego.

Michele Hanisee, the group’s president, said Soros and the ACLU call on prosecutors to “pick and choose” which laws they enforce.

“It is a very, very slippery slope when you are asking the elected official to ignore laws they have sworn to uphold,” Hanisee said.

Behind the publicly reported political spending is millions more in grants to nonprofit advocacy groups. The organizations mobilize members to knock on doors, test political messages and promote liberal candidates and policies.

Many of those activities don’t show up in campaign finance reports. Federal tax laws allow nonprofit advocacy groups to hide the source of their money and to disclose summaries of their spending years after the fact. It will be 2020 before Californians will be able to see the full scale of the involvement in June’s elections.

But tax forms, grant documents and interviews by The Times and the Marshall Project show that a coalition of wealthy donors, private foundations and advocacy groups by last year had sunk $11 million into grants focused on district attorney elections across the nation. At the top is the Open Philanthropy Project, a foundation started by Moskovitz and Tuna, that from 2014 to 2017 directed $6.6 million toward “prosecutorial reform” or similar terms.

Major grant recipients include the ACLU. The group’s projects include national polling last year measuring voter interest in the county races, and score cards helping promote the liberal platforms of candidates in Texas and California. Soros gave $50 million to the ACLU in 2014 for work on criminal justice issues, though it’s unclear how much, if any, was earmarked for the prosecutor campaigns.

A constellation of other San Francisco Bay Area philanthropists and Silicon Valley elite are writing checks alongside Tuna’s foundation, including Kaitlyn Krieger, wife of Instagram co-founder Michael Krieger, and Liz Simons, the daughter of a hedge fund billionaire. (Simons sits on the Marshall Project’s board of directors.)

The collaboration included a panel on prosecutor races last fall at the closed-door retreat of Democracy Alliance, a coalition of groups and leaders who pool their resources behind liberal causes. In July, a similar group, the Tides Foundation, hosted campaign directors for Soros and the ACLU and racial-justice activists from Color of Change to talk about steering nonprofit money toward the cause.

In electing liberal prosecutors, participants said, the groups also seek to build voter bases for larger elections.

The 2016 election in Illinois of Kim Foxx as Cook County state’s attorney illustrated the power of combining national money and local field teams.

The first large checks paid for polling that showed Foxx dead last just two months before the March primary, according to a post-election report by one of the groups that backed her, National People’s Action Campaign.

Foxx’s supporters walked black wards and suburbs handing out fliers. Donations began to roll in. Soros joined the fight. So did Color of Change, Move On and Democracy for America — national organizations also engaged in the California races.

The groups paid for media buys and tapped membership lists for volunteers. Local organizations stepped up field operations and embedded directly in Foxx’s campaign, accomplishing half the get-out-the-vote effort, for free.

Black Lives Matter demonstrators bird-dogged Foxx’s main opponent, a two-term incumbent, the report said, “keeping negative attention on” her delay in bringing murder charges against a Chicago police officer who shot a black teen walking away from officers. Dash cam video of the shooting sparked national outrage and local protests.

Foxx won in a landslide, becoming Cook County’s first black state’s attorney.

The report called the collaboration “a template for the national progressive movement.”

But other candidates have fallen short. Targeted incumbents in Arizona and Colorado survived challenges despite Soros’ heavily funding their opponents.

“We knew that George Soros couldn’t find Jefferson County on a map,” said Peter Weir, who heads the district attorney’s office in the suburbs west of Denver. “Justice was not for sale in Jefferson County.”

Even if they do win, some liberal prosecutors meet resistance to fulfilling their campaign promises.

In Florida, the attorney general stepped in to pursue the death penalty against a man charged with killing a police officer when Orlando’s new state attorney refused. And in Texas, 15 of Harris County’s 16 judges refused to accept the district attorney’s lower bail recommendations.

“We went after the D.A., which is a good start, but we have to change the entire [justice] administration,” said Tarsha Jackson, criminal justice director of the Texas Organizing Project.

The project’s next target? Elect new judges.

[email protected] | Twitter: @paigestjohn.

[email protected] | Twitter: @AbbieVanSickle

This story was published in partnership with the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

The Marshall Project receives funding from the George Soros-funded Open Society Foundations and other organizations that support efforts to reform the state’s criminal justice system. Under terms of its funding, the Marshall Project has sole editorial control of its news reporting.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.