Inflatable dams and a water wheel: Latest plan to revitalize the L.A. River

- Share via

Hydrologist Mark Hanna stood on the North Broadway Bridge recently and gazed out on an industrial vista of treated urban runoff flowing down the Los Angeles River channel between graffiti-marred concrete banks and train trestles strewn with broken glass.

The forlorn scene is in marked contrast to the vision city officials and environmentalists long imagined for the river: Reviving it from a concrete wasteland into a nature center and recreational area.

For Hanna, a big step in that epic transformation involves placing a giant inflatable dam near the historic bridge.

“We expect a final permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers by year’s end,” said Hanna, who helped design the $10-million project for Metabolic Studio, a direct charitable activity of the Annenberg Foundation. “Construction could begin in January.”

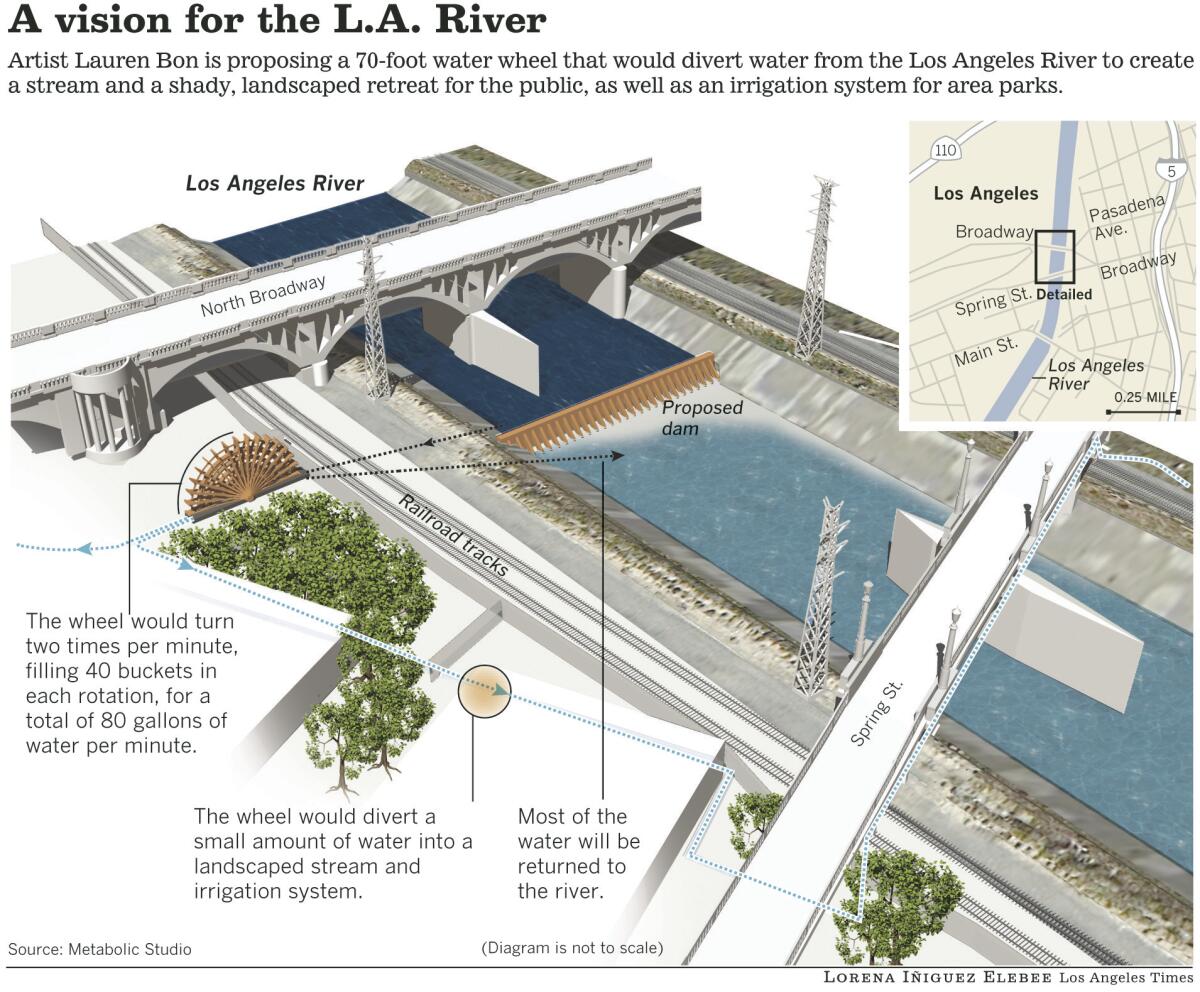

The dam would create an impoundment area that would drive a 70-foot water wheel with buckets designed to lift 80 gallons per minute, splashing their contents into a stream landscaped with cottonwood trees adjacent to the Los Angeles State Historic Park, just north of downtown. It would keep more water in the river, and reduce wastewater runoff into the ocean.

The rubber dam would be among the largest pieces of infrastructure constructed on the 51-mile-long river since the late 1930s, when it was transformed into a concrete flood-control channel to prevent the epic flooding that occurred during wet years.

It might sound like futurist dream. But city officials say the dam also may serve as a template for installing the technology elsewhere along the river to capture some of the tens of millions of gallons of treated wastewater that otherwise drain away into the Pacific Ocean each day.

Selective ponding with rubber dams “is a good idea,” said Adel Hagekhalil, assistant director of the Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, which will operate the system for Metabolic Studio. “We can learn a lot from this project about the feasibility of using rubber dams for a variety of beneficial uses, such as water storage and recycling, recreation and habitat.”

As envisioned by city and county officials and advocates of river revitalization projects, inflatable dams would be raised to create impoundment areas on a short-term basis during low flows that would not be allowed to stagnate or interfere with flood capacity.

A “river revitalization master plan” funded by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and city Department of Public Works-Bureau of Engineering identified 10 potential sites for rubber dams — including three in the downtown area.

The county already uses rubber dams along the San Gabriel River to divert flows and recharge groundwater aquifers, and Orange County Water District has built them on the Santa Ana River. In Tempe, Ariz., a city of about 182,000 people, a complex system of inflatable dams constructed along a usually dry stretch of the Salt River has created a 2-mile-long lakeside district.

Critics, however, argue that a network of rubber dams in the Los Angeles River would encourage more development along a channel that U.S. Geological Survey scientists say is prone to catastrophic flooding every 100 to 200 years.

“The value of true ecosystem restoration along the L.A. River far exceeds the value of these heavy engineering projects,” said Melanie Winter, director of the River Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to responsible management of watershed lands. “The benefits of rubber dams would primarily be aesthetic, recreational and economic, with moderate potential for groundwater recharge.”

Travis Longcore, a spatial scientist at USC, warns of unintended ecological consequences: “We could end up with the equivalent of inflatable beaver dams creating breeding grounds for bullfrogs.”

Lauren Bon, an artist and director of the Annenberg Foundation, says she designed the water wheel project to serve as a symbolic reminder that Los Angeles will always have to rely on limited water supplies delivered over long distance. She calls the idea “bending the river back into the city.”

With that goal in mind, the State Water Resources Control Board in 2014 awarded Bon the right to divert 106 acre-feet of water from the Los Angeles River each year. No other water right has been issued on the river since the city opened the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913.

The Broadway Bridge dam would result in an impoundment about 8 feet in depth and one-quarter-mile wide, creating enough pressure to propel 30 cubic feet of water per second into a 42-inch, 160-foot-long tunnel drilled through the channel’s concrete walls. An array of ultraviolet lamps would be used to kill viruses and bacteria in the runoff.

On the other side of the channel wall, the water would turn the steel and aluminum wheel. Most of the diverted water would be directed back into the river, Hanna said.

Now, as Metabolic Studio awaits approval of its application for a permit to install the dam across the 190-foot-wide channel, “a lot of people have their eyes on us,” said Michael Gagan, a public affairs specialist who has already helped Bon obtain 40 permits from regulatory and municipal agencies, including the Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering, the State Water Resources Control Board, the Los Angeles County Flood Control District, the Southern California Regional Rail Authority, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Metro and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“A rubber dam can change the whole look and feel of riverfront communities that have been staring out at barren concrete for decades,” Gagan said.

ALSO

Supreme Court turns down property-rights challenge to developer fees in West Hollywood

Day of the Dead culture is getting pulled into Halloween's retail vortex

Mother and daughter were holding hands when truck slammed into them. What happened next was shocking

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.