L.A. County’s plan to capture stormwater could be state model

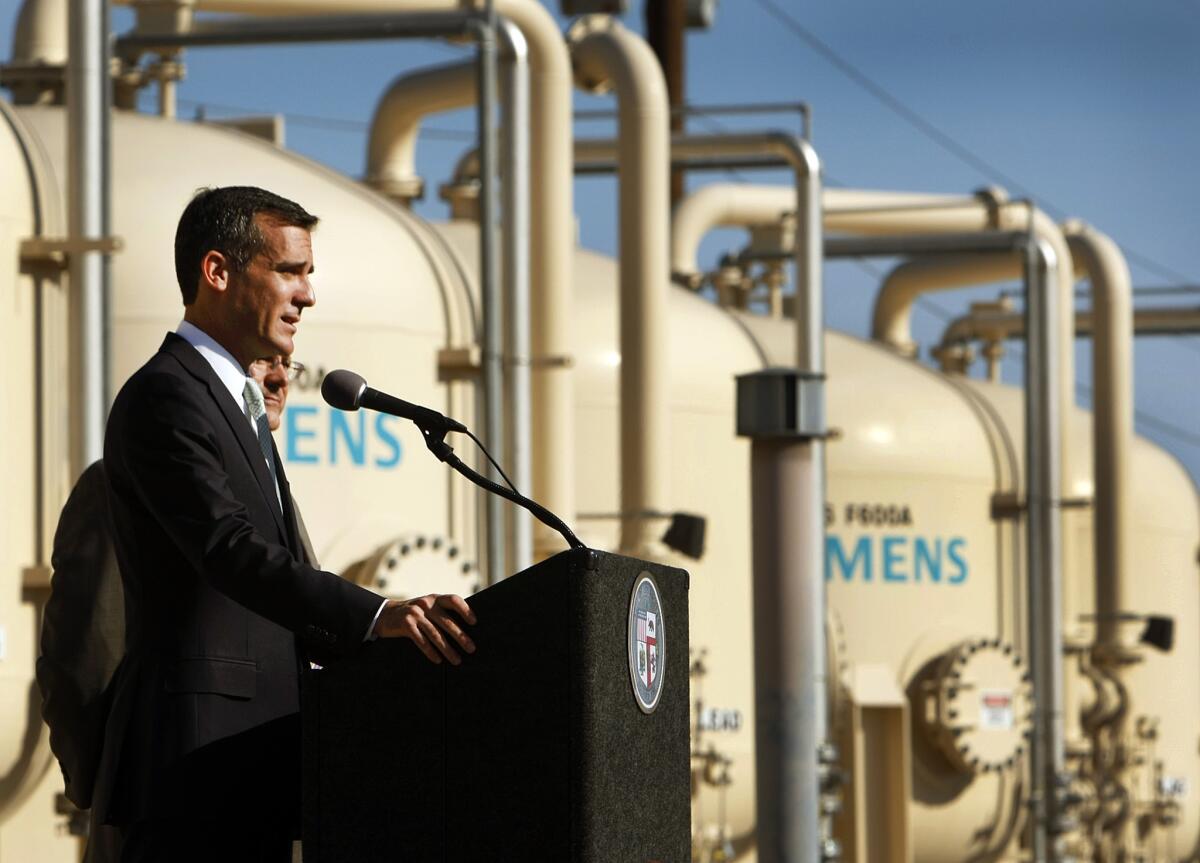

Mayor Eric Garcetti tours the Tujunga Spreading Grounds, a stormwater capture and groundwater replenishment project in Arleta, in 2014.

- Share via

Amid a worsening drought, California water officials adopted new rules Tuesday aimed at capturing and reusing huge amounts of stormwater that have until now flowed down sewers and concrete rivers into the sea.

Federal clean water legislation has long required municipalities to limit the amount of pollution — including bacteria, trash and automotive fluids — that is flushed into oceans and waterways by storm runoff.

But only recently has California considered capturing this water as a way of augmenting its dwindling water reserves. The plan approved by the State Water Resources Control Board applies to Los Angeles County but is seen as a model for other parts of water-starved California.

“This could be quite historic and path-breaking,” said Felicia Marcus, the board’s chairwoman. “Our collective objective should be to use each scarce drop of water, and each local dollar, for multiple local benefits — flood control, water supply, water quality and urban greening in the face of climate change.”

The board voted unanimously to approve a controversial set of revisions to Los Angeles County’s stormwater discharge permit.

Among other things, the revisions provide a framework for cities to plan and build aquifer recharge systems and other forms of “green infrastructure,” officials said.

Proponents of such systems say that rainwater can be captured before it comes into contact with contaminants and funneled into underground aquifers, or over spreading fields where it percolates through the soil.

In other cases, swales can direct the flow of rainwater to areas of vegetation or landscaping instead of plunging down gutters. Water could also be captured in holding areas for use later in irrigation systems.

Some environmentalists strongly opposed the plan, complaining that the changes did not go far enough. And cash-strapped municipalities also objected, saying that they could not afford the expense of new stormwater infrastructure.

“The revised draft order represents a gross abuse of power and an abdication of responsibility,” said Steve Fleischli, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council water program.

Fleischli said the approved rules allowed municipalities in certain watershed categories to avoid the issue of rainwater reuse and also degraded the state’s ability to enforce water quality. He said he feared the regulations would allow some cities to plan water capture systems without ever having to build them.

The Natural Resources Defense Council has argued that stormwater capture could potentially provide more than 253,000 acre-feet of water for Los Angeles County after every inch of rainfall — or nearly 40% of the city of Los Angeles’ annual water use.

“This is a missed opportunity,” Fleischli said.

Water board members said they were satisfied with the wording of the changes but acknowledged that verification would be the key to ensuring that municipalities followed through with their plans.

“This is a risk we’re willing to take to a point,” board member Steven Moore said. “But if we hear from our permitees that they don’t believe this is meaningful and that they don’t buy into green infrastructure and they think it’s too expensive and the heck with it.... That’s a big problem.”

The revised permit has been the topic of dispute for a while now. The state water board had received 37 petitions challenging various provisions of the Los Angeles County MS4 Permit and sought to resolve those concerns before arriving at the current revision.

While government organizations such as the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works voiced support for the revised permit, a number of municipalities said they were alarmed by the potential cost.

Gardena City Councilman Dan Medina said compliance with the permit threatened to “bankrupt our city and probably force it into a disincorporation.”

Medina said a consultant had told the city that belonging to an enhanced watershed management program could cost the city $12 million to $24 million a year.

“The city’s general fund is only about $50 million a year,” Medina said. “Nearly 80% of that goes to public safety.”

However, other speakers at the board meeting said the model that consultants were using to estimate costs was flawed.

Marcus told municipal officials that the estimates seemed too high.

“The lowest-cost thing that gets the job done is what you want people to do,” Marcus said.

ALSO:

43 ways to save water during the drought -- while still keeping the lawn

Trying to cultivate respect for water regulations among pot growers

$110 million in drought aid going to California, other Western states, White House says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.