Homeless woman’s case sharpens focus on justice system and mentally ill

- Share via

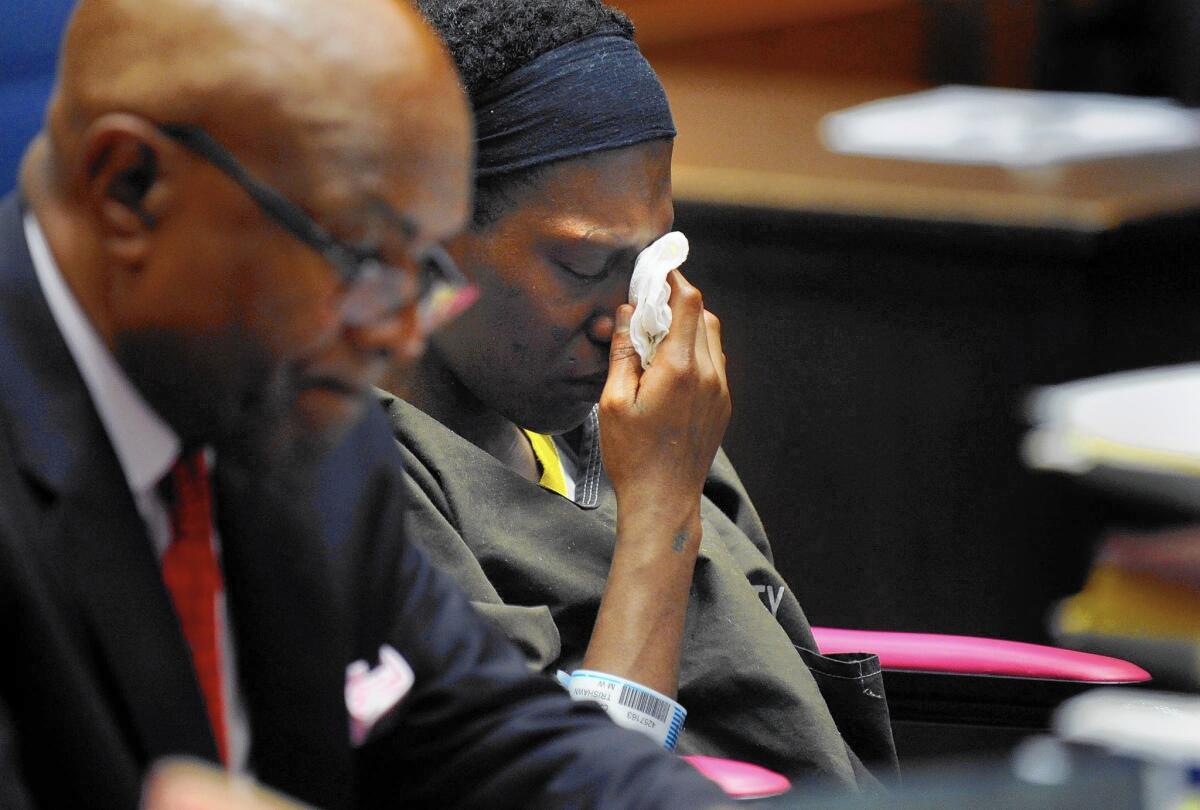

The list of Trishawn Cardessa Carey’s prescriptions fills a page in her case file: clonazepam for seizures and panic, methocarbamol for muscle spasms and quetiapine for spells of psychosis. She suffers delusions, paranoia and “dramatic mood swings.”

For years, the homeless woman has lived off Social Security tied to her mental disability — a doctor diagnosed her with schizoaffective disorder — and she has cycled into and out of L.A. County jails 10 times since 2002, according to court documents filed by her attorney, Milton Grimes.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Homeless woman: In the July 24 Section A, an article about a homeless, mentally ill woman being prosecuted after hoisting a police officer’s dropped nightstick referred to a charge of attempted assault. There is no such crime in the penal code; the correct term is assault. —

------------

Carey now could face decades in prison after picking up an LAPD officer’s baton and raising it in the air during a violent skid row incident earlier this year. The case spotlights a challenge for officials as they begin a new effort to improve the way Los Angeles’ criminal justice system handles offenders with mental illness.

Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey, whose office is prosecuting Carey, announced this week details of an ambitious plan to keep more mentally ill people out of jail and to get them help instead.

Late Thursday afternoon, her office said Lacey “didn’t learn of the specific charges or that the defendant was mentally ill until this week,” and had asked managers to review the case.

More than 3,000 people in the L.A. County jail system — about one-fifth of all inmates — require mental health services, sheriff’s spokeswoman Nicole Nishida said.

The long-awaited plan, which was discussed at a public safety meeting Wednesday, focuses on training law enforcement in how to de-escalate encounters with mentally ill people and opening treatment-based housing.

The draft, however, did not detail specific ways the district attorney’s office might alter its approach to prosecuting in cases involving mentally ill people. In an interview, Lacey said her job is to balance public safety and victims’ rights, as well as doing “the right thing by people who are ill by no fault of their own.”

“Those people who are mentally ill and homeless are the toughest,” Lacey said. “It’s time for L.A. County to create alternatives for these people who have been involved in the criminal justice system, who are mentally ill and who are homeless and need a place to stay.”

Prosecutors charged Carey, 34, with assault with a deadly weapon against a police officer, and she could face 25 years to life in prison under California’s three-strikes sentencing law. The charge stems from her role in the March 1 incident on skid row, which was captured on video.

In the moments before LAPD officers shot and killed Charly Leundeu Keunang, who police say grabbed an officer’s holstered gun, Carey picked up a dropped nightstick and faced the officers while holding the baton in the air. Although she never swung at them, prosecutors say an attempt to strike someone is enough to charge a person with assault.

Advocates for L.A.’s homeless and mentally ill communities support the new effort to reduce recidivism by the mentally ill by providing them with better services. But some question the district attorney’s charges against Casey.

“She is a homeless mentally ill woman being charged with an assault with a deadly weapon. … That seems excessive,” said Heather Maria Johnson, a staff attorney for the ACLU of Southern California who focuses on homelessness issues. “It’s all too common for homeless individuals, in particular with mental health issues, to be overcharged.”

Carey’s previous strikes stem from a 2002 robbery in which she punched a victim in the head and a 2006 assault with a deadly weapon. Grimes, her attorney, said both incidents were intrinsically tied to her mental illness.

Retired UCLA law professor Gary Blasi, who has studied homelessness, said Carey’s case underscores the need to rethink how the criminal justice system handles the mentally ill.

“They are just dealing with symptoms,” he said. “They are doing nothing more than recycling people through the criminal justice system.”

On Wednesday, Lacey spoke broadly about prosecuting mentally ill people, saying it sometimes must be done to keep the public safe.

“There are times where people commit crimes … where they’re just going to have to be punished,” Lacey said.

Loyola Law School professor Stan Goldman said charging Carey with assault was “a close call,” but added that assault doesn’t require actual battery, only threatening behavior.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

July 24, 2:52 p.m.: An earlier version of this article referred to a charge of attempted assault. There is no such crime in the penal code.

------------

Goldman said prosecutors face “real pressure” from victims and their families who demand accountability to put cases involving serious crimes before a judge and jury — even when the defendant claims mental illness.

Goldman, a former public defender, said he expects Carey’s attorney to make one of two arguments at trial: that Carey was never really menacing to the officers, or that the officers had crossed a line and she was acting in defense of Keunang.

In several letters submitted to the court, people who knew Carey asked that the charges be dropped so she could get help in a different setting. A nurse who cared for Carey said she spoke of “very bad things” that happened to her as a child and argued that treatment — not incarceration — would be beneficial.

A volunteer with a skid row advocacy group described Carey as a soft-spoken, gentle woman who once smiled when she joked with her that a stripe of toothpaste in Carey’s hair — something Carey couldn’t explain — looked like warrior paint.

Carey’s sister wrote about her years-long and frustratingly unsuccessful battle to get her help. Her sister said she contacted various institutions during one of Carey’s psychotic episodes. Everyone seemed to have the same, unsatisfying answer: If Carey didn’t plan to kill herself or someone else, she couldn’t get the help she needed.

“Why is there not a promoting of well-being instead of preventing harm?” her sister wrote. “Stop criminalizing the mentally ill.”

[email protected]

Twitter: @marisagerber

[email protected]

Twitter: @lacrimes

Times staff writer Gale Holland contributed to this report.

ALSO:

Autopsy pending for reality TV star killed in Redondo Beach

LAPD officer gets 36 months in jail in assault caught on video

Retired LAPD detective arrested, believed to be elusive ‘Snowbird Bandit’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.