Union-commissioned report says charter schools are bleeding money from traditional ones

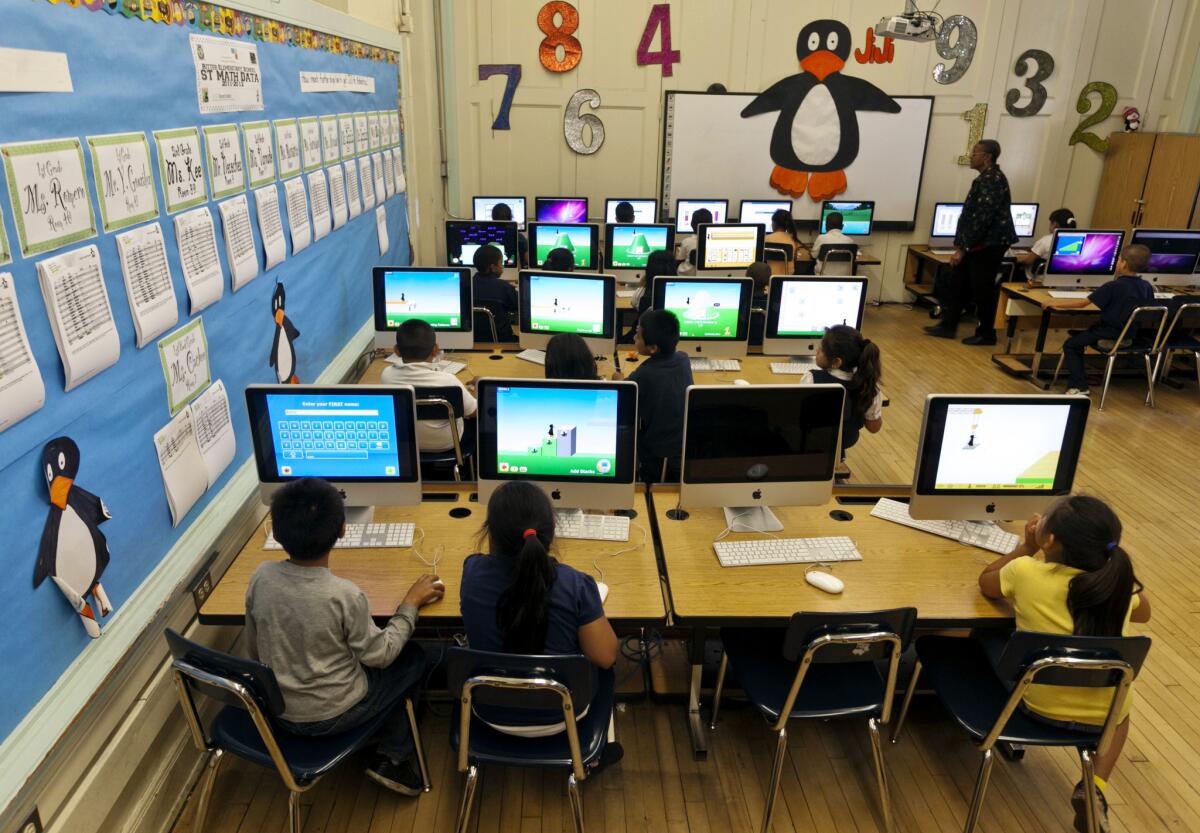

Ritter Elementary School students practice their math skills in Los Angeles.

- Share via

A teachers union-funded report on charter schools concludes that these largely nonunion campuses are costing traditional schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District millions of dollars in tax money.

The report, which is certain to be viewed with skepticism by charter supporters, focused on direct and indirect costs related to enrollment, oversight, services to disabled students and other activities on which the district spends money.

L.A. Unified has the most charters — 221 — and the highest number of charter students — more than 100,000 — of any school system in the nation. Charter students make up about 16% of the district’s total enrollment.

The union gave The Times the study in advance of its scheduled presentation at Tuesday’s Board of Education meeting, with the stipulation that the report not be distributed to outside parties.

The study calculates that services to charters encroach on tax money the district intended to use for traditional schools, adding up to at least $18.1 million a year and growing.

The biggest financial problem for the district, however, is that money follows students and a huge number of students have enrolled in charters instead of traditional district schools. With more education tax dollars going directly to charters, the result is a decline of more than $500 million a year — about 7% — in the district’s core budget, the researchers say.

The effects of this drop are difficult to quantify because fewer students in traditional schools also means a reduced need for teachers and other personnel.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

But even with reduced staffing, the district faces a net loss of about $4,957 per student, the study says. That amount accounts for fixed costs, such as maintaining buildings.

Whatever the exact amount, the district has less money to spend with the flexibility its leaders would prefer or to offset legacy costs that include aging school buildings and retiree health benefits.

“The findings in the report paint a picture of a system that prioritizes the growth opportunities for charter school operators,” according to a separate policy brief co-written by the union.

Charter supporters take a different view, seeing the district as the fundamental problem and charters as an important solution.

“Like all businesses, the district has to compete for its customers,” said Eric Hanushek, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

“The growth of charters is putting pressure on the district. The district can’t do what it did in the past and come out ahead,” added Hanushek, who hadn’t seen the report. “They can try to compete for the students or sell off the buildings. But the point is: Charters look attractive to parents, which means that the district is not attractive.”

Prompted in part by concern about the district’s judgment in how it spends money, a group of philanthropists and foundations has bet big on charters in Los Angeles, subsidizing their growth over the last two decades. Last year, local philanthropist Eli Broad spearheaded a proposal to more than double the number of charters over the next eight years, hoping to reel in half of district students.

About six months ago, a group formed to develop Broad’s vision for new, high-quality schools.

Meanwhile, both the district and employee unions have been trying to develop counter-strategies. From the district, the push is to increase enrollment, to compete with charters more aggressively and possibly to limit their growth. Until now, the union has been most visible at the bully pulpit, speaking at gatherings and leading demonstrations.

The new report is from Florida company MGT of America. It builds on the work of an earlier, independent district advisory panel, which concluded that charter growth is one of several factors threatening the solvency of L.A. Unified.

This latest analysis was reviewed by pro-labor Washington group In the Public Interest, which prepared the separate policy brief with the union.

“Unmitigated charter school growth limits educational opportunities for the more than 542,000 students who continue to attend schools run by the district, and … further imperils the financial stability of LAUSD as an institution,” the brief states.

Charters pay 1% of the tax money they receive from the state to the district for oversight through its charter division, but this isn’t enough, according to the report. The charter division monitors academic progress at charters and reviews their financial health and management practices.

The division spends about $2.9 million more than the available funding, which is limited by state law.

The report also tallies an additional $13.8 million in annual administrative costs related to charters, and $1.4 million more for work by the district’s inspector general and special education division.

The full effect on services to the disabled is actually much higher but difficult to nail down, according to the researchers.

The federal government mandates that every disabled student should receive a free and appropriate education, but does not fully pay for it. The state, in turn, spreads out this funding equally between students, regardless of their disability. L.A. Unified enrolls a much higher percentage of the disabled students who cost more to educate.

“A student with a need for speech therapy might need only monthly support/monitoring that might cost the district $3,000 per year,” the report states. “A student with emotional/behavioral or health impairments with significant needs might need residential placement or daily feeding or medical monitoring and might cost the district upward of $120,000 per year.”

Schools and districts pool their resources — and share the expense — of serving disabled students, but L.A. charters don’t have to partner with L.A. Unified. Some have cut costs by affiliating with another district. To keep other charters in the fold, L.A. Unified provides a special deal that essentially shortchanges the district, the report concludes.

Another indirect cost of charters relates to audits and investigations conducted by the district’s inspector general. A routine audit takes three to six months and costs about $70,000. More extensive reviews cost at least twice as much.

The California Charter Schools Assn. has challenged the need for much of this work, calling many of these investigations unneeded and intrusive.

Jason Mandell, a spokesman for the association, said in an email that he could not comment on the report because he hadn’t seen it. But any focus on charters, he said, was intentional misdirection away from financial problems that are of the district’s own making. He noted that the earlier advisory panel study concluded that “even if charter schools didn’t exist, the district would still face a crippling decline in enrollment due to entirely separate factors.”

The MGT report, which cost $82,000, doesn’t fault charters, saying that the problems have more to do with state and federal policies as well as district decisions.

But in the policy brief,

the union takes a more aggressive tone, arguing for changes that include full funding from the federal government for disabled students and equitable distribution of these dollars by the state; more money for charter oversight — either from the state or from charters; and charging higher district fees, where possible, to charters.

Twitter: @howardblume

Editor’s note: Education Matters receives funding from a number of foundations, including one or more mentioned in this article. The California Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Los Angeles administer grants from the Baxter Family Foundation, the Broad Foundation, the California Endowment and the Wasserman Foundation. Under terms of the grants, The Times retains complete control over editorial content.

ALSO

School principal: ‘Harry Potter’ and ‘Lord of the Rings’ cause brain damage

Students need to stop being so sensitive and let Madeleine Albright speak

UC regents get their first chance to weigh in on scathing audit of admissions policies

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.