Thanks to Good Samaritans, homeless vet was lost but not forgotten

- Share via

He was sitting on the apartment steps in her placid West Los Angeles neighborhood, his cottony Santa Claus beard clotted and his clothing unwashed. He struggled for words, and couldn’t explain why he was there or where he was going.

Mehrnaz Davoudi had never volunteered to help homeless people, or taken one home. But when she saw Donald Reynolds, she saw a fractured reflection of her father, an Iranian immigrant who had descended into dementia before his death the year before.

Davoudi found herself wandering with Reynolds for hours, seeking in vain for the place he belonged, before driving him to a downtown shelter.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

The next day, Reynolds had disappeared into the maw of skid row. For almost a month, Davoudi would search amid the jumbled heaps of clothing and tarps and plead for help from authorities. Strangers who also saw someone else in Reynolds protected him as he made his way.

“I keep having a gnawing feeling Don needs help being found,” Davoudi said.

::

I said, ‘Which way should we go?’ He looked up and said, ‘Where are we?’ I couldn’t just say goodbye and good luck.

— Mehrnaz Davoudi, on trying to help homeless veteran Donald Reynolds

Her father’s dementia came on gradually four to five years before his death from prostate cancer. Davoudi and her sister, Farnaz, nursed him through the long illness; he died in Mehrnaz’s apartment.

“He was a very, very strong man, a wonderful man,” said Davoudi, 40, a program evaluator for a nonprofit health system.

Like her dad, Reynolds, 80, was a storyteller, Davoudi said. He was hopeful, believed in the good in other people and wanted to help himself.

On that October day, Davoudi decided she had to do what she could to get him off the streets.

“I said, ‘Which way should we go?’ He looked up and said, ‘Where are we?’ ” Davoudi said. “I couldn’t just say goodbye and good luck.”

Davoudi sat him in her driveway and dressed a wound on his arm. Davoudi had called her sister to gather some contacts. A homeless outreach worker said he couldn’t come that day, but mentioned that if Reynolds happened to be a veteran, there were lots of resources. Los Angeles was in the midst of the biggest push in the nation to get its homeless veterans, the most of any city, off the streets.

Reynolds said he was an Army veteran. The Veterans Affairs office suggested names of shelters.

Some didn’t answer the phone; others were full. The Los Angeles Mission said it would take him.

During the hourlong drive crosstown, Reynolds volunteered a bare-bones life story: He was one of six children, and when he was young, his mother was shot and killed by her alcoholic husband after she threatened to call the police on him. He was vague if it was his father or a stepfather.

His three sisters were taken away by “a man from Sacramento,” and he lost track of them. He said he had no wife, no children, no family.

He thought he had lost his truck to $700 unpaid parking fines and a storage unit with “25,000” books and paperwork, including news clippings about his family tragedy.

“What a day. I get on a bus to try to do something, and everything changes so fast,” he said. “You girls shouldn’t have to help me. I feel ashamed.”

“I said, ‘You have nothing to be ashamed of. Everybody needs help sometime,’ ” Davoudi replied.

Davoudi explained Reynolds’ memory problems, and the shelter promised to look after him. At her urging, Reynolds locked his wallet in the shelter’s vault.

The next day, he walked out, leaving even his wallet. “Sometimes they won’t stay put long enough for us to help them,” said Tim Law, the mission’s emergency services chaplain.

Davoudi drove to skid row again. Her sister stopped three LAPD officers. “Why the heck did you take him here?” she said one told her.

The desk officer at the station house wouldn’t take a missing persons report, she said. “Once he realized he was homeless, he put his pen down,” Davoudi said. An officer ran his name and said his last known address was Canoga Park, 30 miles and several bus routes away.

“Then we were really worried,” Davoudi said. “He was lost and far away from everything he knew.”

::

Two days after Reynolds left the mission, Doelorez Mejia saw a man with a long white beard, stooped over and gazing at the ground in Hollenbeck Park at dusk.

The urban oasis is two miles from skid row. Mejia, a longtime community activist, was living in her silver Chevrolet Cavalier, her belongings piled on the back seat under a blanket, and sometimes used the park bathroom to “give herself a little birdbath.”

Reynolds reminded her of her brother, “so good-natured.” She asked him if he’d eaten, and gave him a yoga mat and a Dodgers rain poncho.

“I’m always picking up things for other people. That connection I do believe that is what grounds us,” Mejia said. “Otherwise we’re just colliding corpses on this planet.

“With that beard, he reminded me of Father Time, lost in a time warp.”

She wrote her name and number and contacts for a Boyle Heights shelter and the local office of Volunteers of America, a homeless agency, on a slip of paper for him. He wandered off into the night, she said.

A block away, a dance performance was ending at Mercedes Hart’s Boyle Heights art gallery when she noticed the man with the ivory beard sitting on the stage. She got him a chair, and he nodded off.

“It was completely magical,” Hart said. “Definitely a powerful energy.”

Reynolds reminded Hart of her grandfather, who at the end of his life no longer recognized his children.

She was nervous, but she decided to let him stay the night in the gallery space. In the morning she asked where he lived. “Well, right here, I guess,” Reynolds replied.

“I thought, ‘Oh dear. No,’ ” Hart said. She had hoped Reynolds lived nearby and she could visit, but she couldn’t take him in. Hart walked him to the Volunteers of America office that Mejia had listed for him and waited while they processed him.

::

Back on skid row, Davoudi retrieved Reynolds’ wallet and found a contact for his social worker, who said the elderly man had been homeless for 15 years. The social worker called the skid row station for her and told her to return with missing persons’ fliers with Reynolds’ picture.

Los Angeles Police Department Sgt. Deon Joseph, skid row’s longtime senior lead officer, was at the desk when she arrived and told him to take the report. Joseph promised the department would alert the missions and outreach workers to be on the lookout.

Det. Cletus Carlton of the LAPD’s missing persons unit called and said he was surprised Davoudi had had trouble making the report because elderly dementia patients are high priority, Davoudi said.

“Sometimes they pass it off because if he’s a transient, why do they need to take a report? He’s already missing, he’s in the streets,” Carlton said later. “It’s a noncrime report.”

Nearly a month after Reynolds disappeared, Davoudi emailed The Times for help.

Reynolds “deserves to be supported by the community just as if he was someone’s father and grandfather … not just a nameless ‘homeless veteran,’” she said.

The paper contacted Vince Kane, whom VA Secretary Robert McDonald had sent to Los Angeles to tackle the veteran homelessness problem. Within two hours, Kane had an answer: Volunteers of America had taken Reynolds to the VA’s emergency homeless outpatient clinic. He was in the VA hospital, half a mile from Davoudi’s home.

“Certainly the communication could be better,” Kane said. “The message should be take him to the VA. Thank God he’s OK.”

::

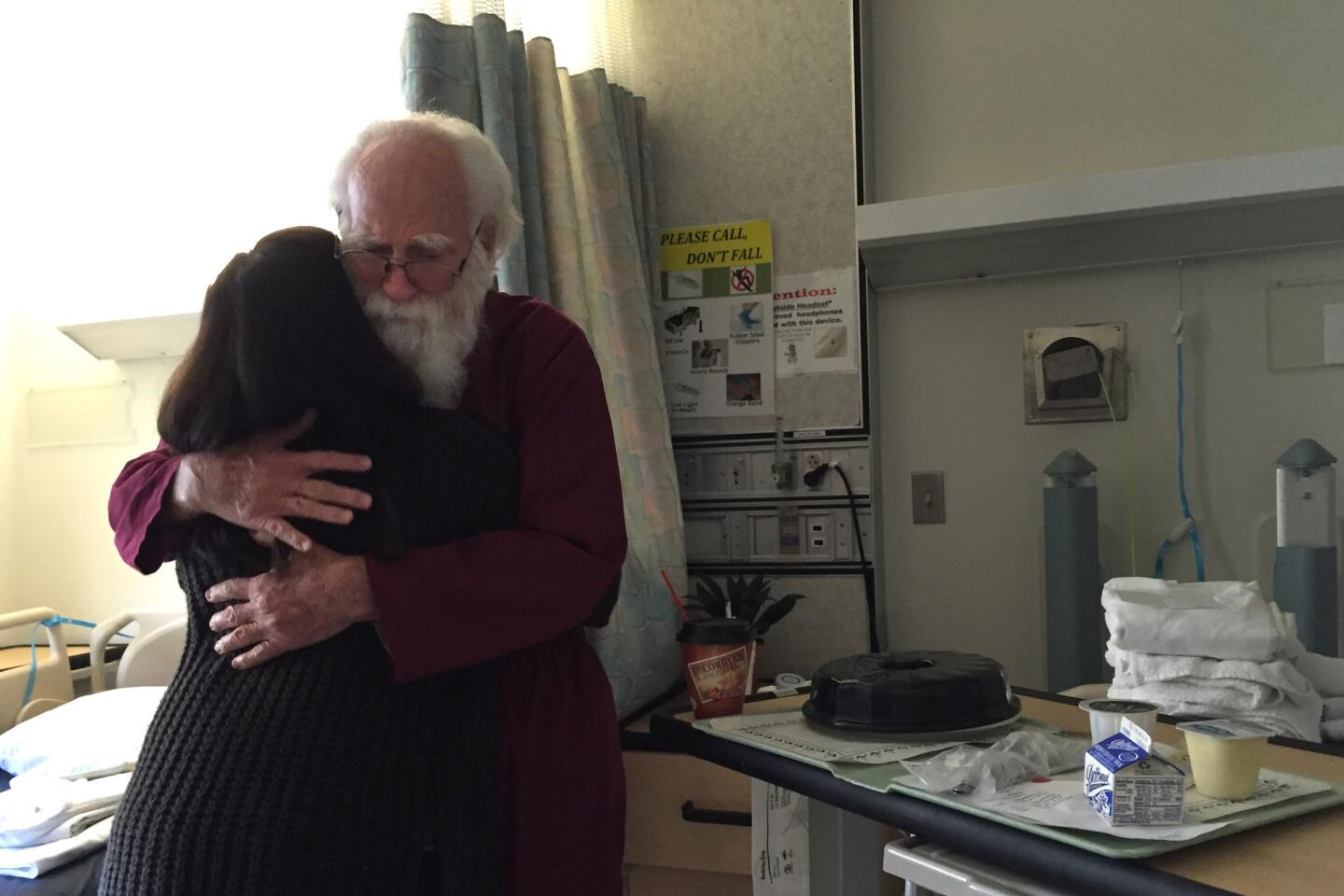

Reynolds didn’t seem to know Davoudi when she walked into the hospital, but he wrapped her in a hug. “I sure am glad to see you,” he said.

He’s remembering more, including the name of the owner of his storage facility in Reseda, and the make and model of his truck.

It turned out that Jesse Ballard, the storage owner, had held on to his books, though his rent was in arrears. Not 25,000 of them. “More,” Ballard said. For years, Reynolds had dropped by weekly to add four or five volumes to his collection, mostly science and math books.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

“He’s a very intelligent guy, sharp as a tack,” Ballard said. “Three months ago, I realized he was starting to lose it.”

Reynolds said his favorite book was “Black Beauty,” the children’s classic told through the eyes of a horse. Black Beauty is a well-bred carriage animal who is mistreated and descends the equine social ladder to pulling cabs in London, before finally ending up with a happy retirement in a grassy paddock.

“My troubles are all over, and I am at home,” Black Beauty says near the end of the novel.

Reynolds has not yet found his happy ending. He remains frustrated in the VA hospital, awaiting a conservator to make his housing decisions for him.

He has experienced moments of casual and perhaps unintentional cruelty. “He doesn’t know anything,” a nurse told visitors last week. “What did you say to me?” Reynolds retorted, furious, his eyes filling with tears.

Davoudi urged him to continue standing up for himself. Everyone did the best they could to help him, but “the systems don’t work together like we think they should,” she said.

“This is really not even a story about homeless people,” Davoudi said. “It’s about our elders. He has years of joy to give someone.”

Twitter: @geholland

ALSO

Even for the active, a long sit shortens life and erodes health

Man sought after Pomona woman is doused with gasoline, set on fire

UC system divests $30 million in prison holdings amid student pressure

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.