Great Read: Skid row singers soothe their bruised souls — together

- Share via

The Colburn Wesley Project singers stepped out onto the 51st floor of a downtown Los Angeles skyscraper to make their debut.

Dressed in lace, pearls and tailored suits, they mingled with the benefit’s celebrity emcee, a statuesque former “Basketball Wife,” and her football player boyfriend. Guests in cocktail dresses posed for photos and bid on Hello Kitty merchandise at the silent-auction table.

Under the bristling chandeliers of the City Club, the singers sat down to salad, saving the main course — salmon or steak — for later. The five women and three men, strangers to one another just a few weeks earlier, walked onstage and for the next 17 minutes raised their voices:

“You gotta be bad, you gotta be bold, you gotta be wiser

You gotta be hard, you gotta be tough, you gotta be stronger …

I know, I know love will save the day.”

When the evening ended, the guests would pay $35 for their parking and head for the freeways.

The entertainers would board a bus to take them home: the sidewalk shantytowns, shelters and SRO hotels of skid row.

::

Linda Evans, the choir’s co-director, knew it wouldn’t be easy to start an ensemble amid the chaos of skid row: She’s lived there five years, after an abusive marriage left her homeless and despairing.

“What fascinates me about the choir is it really shouldn’t exist,” said Evans, who now lives in a skid row apartment.

Evans, 64, talks about being discovered by a Capitol Records rep as a 15-year-old singing “Stop! In the Name of Love” in the middle of her Compton street. She worked as a soul and disco recording artist, backup singer and songwriter.

“For a while I was also a poet, but in the ‘60s everybody black was a poet,” Evans said, laughing. “And I was a revolutionary.”

Sick of being on the road, she completed her college degree and worked as a drug counselor and domestic-violence educator. Then she landed on skid row.

“I surrendered mentally, emotionally to the fact that Linda … you’re at the bottom, you live on skid row and you’re on food stamps, OK? You’re not a Supreme, you’re not any of those things,” she said.

Evans was asked to join the singing group by an old friend at the John Wesley Community Health Institute, which paired with the Colburn School of Music to start the choir.

Located blocks from each other in downtown Los Angeles, the school and the institute’s skid row clinic are worlds apart. Situated amid the high-rises off Bunker Hill, the Colburn School educates some of the world’s most talented young musicians. The medical clinic helps care for the people of skid row, 60% of whom it estimates are mentally ill, drug- or alcohol-dependent or both.

Organizers hoped the ensemble could be a new treatment model for skid row’s bruised souls.

“Is there another way to heal people on skid row, other than go to the mental hospital, go to the clinic, go to the drug program?” Evans said. “What about going inside, singing … and let the universe work?”

But they worried that no one would stick to a schedule, or even show up. Sobriety and mental stability were question marks.

Evans and her clinic friend took over recruitment. Evans trolled karaoke night at a skid row church and the sidewalks.

“I actually walked down the street and said, ‘Can you sing?’” Evans said.

Evans and Leeav Sofer, her co-director, set an ambitious goal: a performance at the Wesley clinic’s Oct. 25 banquet after eight weeks of rehearsal.

::

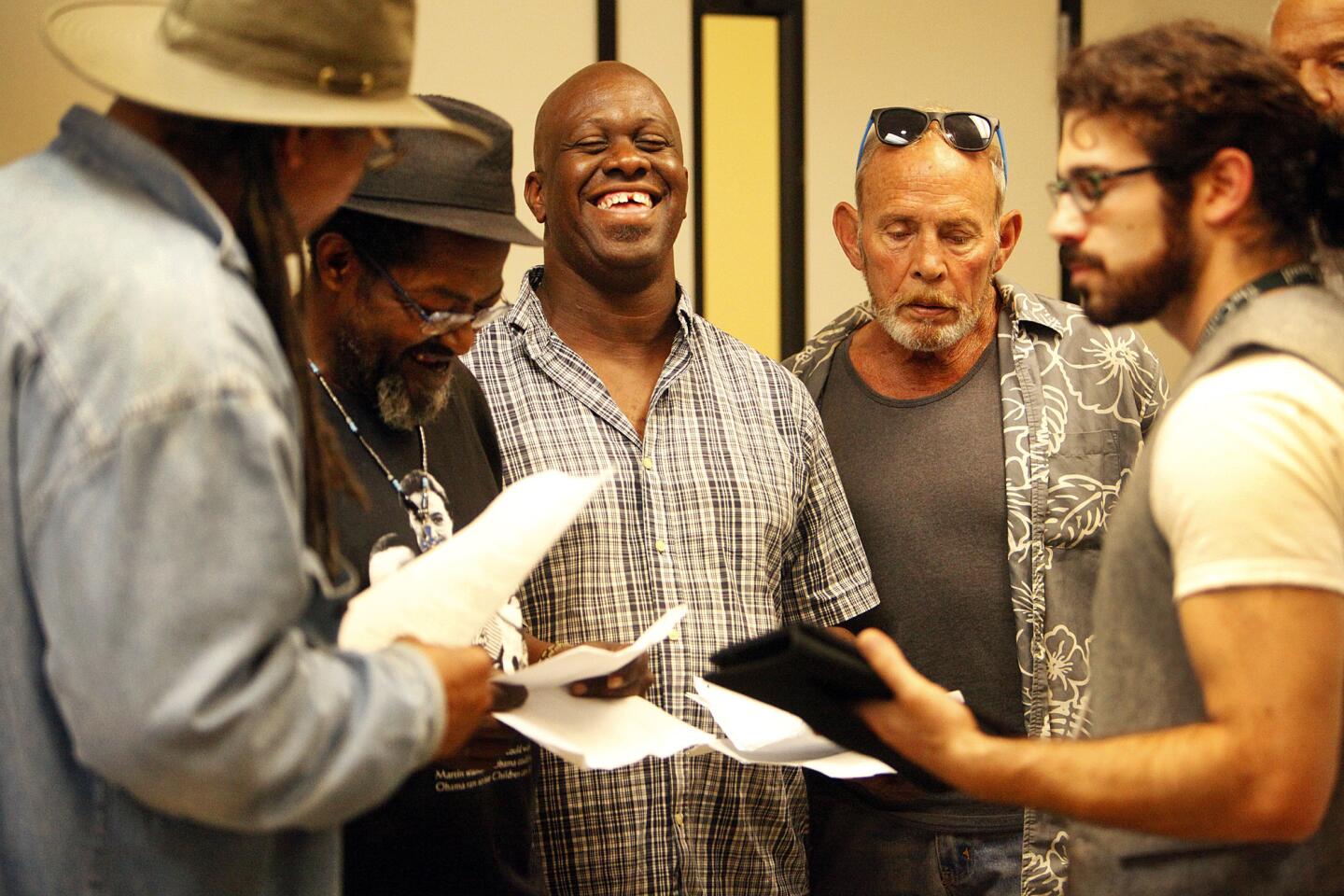

Twice a week, the singers passed by the clinic’s plexiglass barrier and metal detector into a modest conference room, where Sofer provided vocal training and accompaniment on a 64-pound keyboard he hauled in from his car.

Sofer, 24, grew up in northern Orange County and has a degree in opera and clarinet. He headed choirs and a Jewish youth orchestra before the Colburn hired him out of college to teach choral music to underserved high school students.

Solidly built, with springy black hair barely tamed by a ponytail, he sprinkled his instruction with “Star Trek” and other pop culture references.

His first contact with skid row came in college, when he was biking through downtown and “boom, I hit right on, what is it, 6th? ... There’s tents, there’s people lining the walls, just in the middle of the day.”

He quickly charmed the singers, some of them three times his age, talking cars and meeting them for breakfast and lunch outside practice.

“If you sing in a choir, it dissolves so many barriers,” he said. “And all of a sudden you become a family.”

Evans, lithe and intense, brought showbiz razzmatazz, her lead vocals and an understanding of the singers’ lives.

“A lot of horror goes on downtown; it’s dark, and it’s dirty and it’s evil,” Evans said. “I tell them, you’re better than that.”

The gospel and pop anthems she chose for the group had an aching resonance for people who’d been at the bottom.

“We fall down, but we get up

For a saint is just a sinner who fell down

But he didn’t stay there … and got up.”

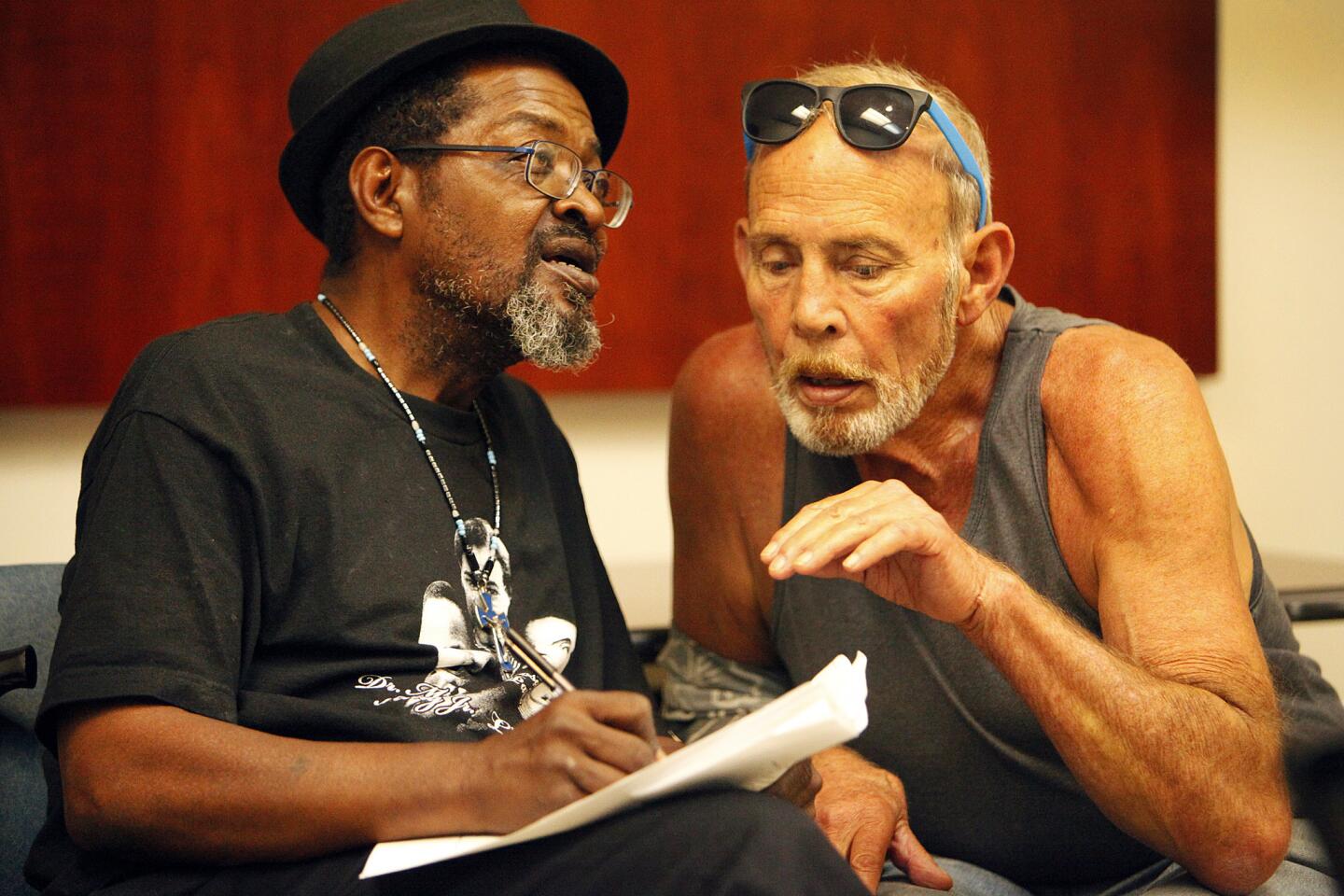

“I internalized those words long before I heard that song,” said Douglas Leigh-Taylor, 69, a former lawyer who became addicted to heroin after the death of his only child.

“We don’t all get up. I got up,” he said during an interview at his skid row apartment. “And I don’t quite know how I got up.”

Homelessness posed unique problems for a fledgling singing group — among them little or no privacy for those living in the street or a dormitory-style shelter. Evans told choir members to practice while walking down the street. Singers came and went, including a heroin user who wanted to proselytize for his church and a veteran with Alzheimer’s.

James Walton, a former drug and alcohol abuser who got out of prison a year ago, couldn’t get the songs to download to his phone, so he lay on his bed at the Weingart Center’s homeless facility and went over the numbers from memory. Jhoanny Guzman, a soprano who lived in the streets of Hollywood and skid row, lost her phone.

Day by day, a core group of eight to 10 members coalesced. In early October, a film financier arrived with black evening-wear to donate for the performance.

“They’re a bunch of Cinderellas and Prince Charmings, and for them this is a dream,” Evans said. “It’s, like, one minute ‘I live on the ground at the Midnight [Mission]’ to ‘who’s doing my hair?’”

::

The clinic closed for Columbus Day, so Sofer ordered a bus to take the choir to the Colburn School campus for practice.

Violin virtuoso Jascha Heifetz’s wood-paneled home studio had been painstakingly reassembled on the school’s second floor.

The rehearsal room had baffled walls and music stands. Sofer sat at a Steinway baby grand with a mirror finish.

The singers stumbled over the words to several songs. Sofer led them in mnemonic memory drills.

After practice, the buoyant crowd spilled into the elevator, singing all the way down, past the security guard into the plaza:

“I look in your eyes. I know your fight, I know your troubles … waiting in line, praying this time, life won’t pass you by.”

“There’s something there that no other choir has, which is the fact they want it so much more,” Sofer said.

::

With only days to go, the singers still didn’t have the lyrics nailed.

Evans blew up. “Does anybody know the words?” she asked. “I don’t know what to do, but I know this is not working.”

Sofer gave a pep talk. “I think you guys can do it. You guys can rise up to this. It’s fine to feel the pressure, feel the heat. Let it fire you up.”

Sofer asked if anyone wanted to tell his or her story during the performance.

Leigh-Taylor stepped forward and ad-libbed, as the choir hummed behind him.

“Chasing the dragon, facing the dragon

Living in his cave.

I saw the light, I found the fight

And climbed to a new life.”

“This is the most organic thing that ever happened,” Sofer said.

With the show so close, he offered to come early to the next practice.

“I totally will not be surprised if I show up … and no one is here,” he said.

But when he arrived, choir members met him in the clinic waiting room, and they sang in the aisles. Moving to a back alley, they formed an a cappella singing circle, like a 1950s doo-wop group.

They were finally pulling together.

::

On performance day, the bus had to chase down Guzman, who had tried — and failed — to get her evening clothes out of storage.

“They won’t let me in because I lost the ticket,” she said.

The Ketchum-Downtown YMCA stayed open late for the singers to shower; not everyone had bathroom access. The singers marveled at the gym’s glass-enclosed pool and swanky appointments.

The women donned wigs, clasped pearls and sponged on makeup.

“C’mon divas,” Evans called.

At the City Club, Walton, the grandson of a preacher, said a prayer.

“You’ve spent time thinking about what those words are,” Sofer told the singers. “You need to start thinking about what the words mean.”

They took the stage. People at the back tables kept talking. There were a couple of shaky moments: an unintentional pause, fumbling for words.

Walton, who a year earlier had been in Folsom State Prison, worked the crowd, shaking hands and rapping. Guzman’s choreography was Temptations-worthy.

Leigh-Taylor blew kisses with both hands at the audience.

“Do you know what you did out there? Do you know what you did?” Sofer asked afterward.

“We did what we were supposed to,” Walton said. “We came together.”

Twitter: @geholland

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.