Great Read: Nuclear accord paves way for importing Persian rugs into U.S. again

- Share via

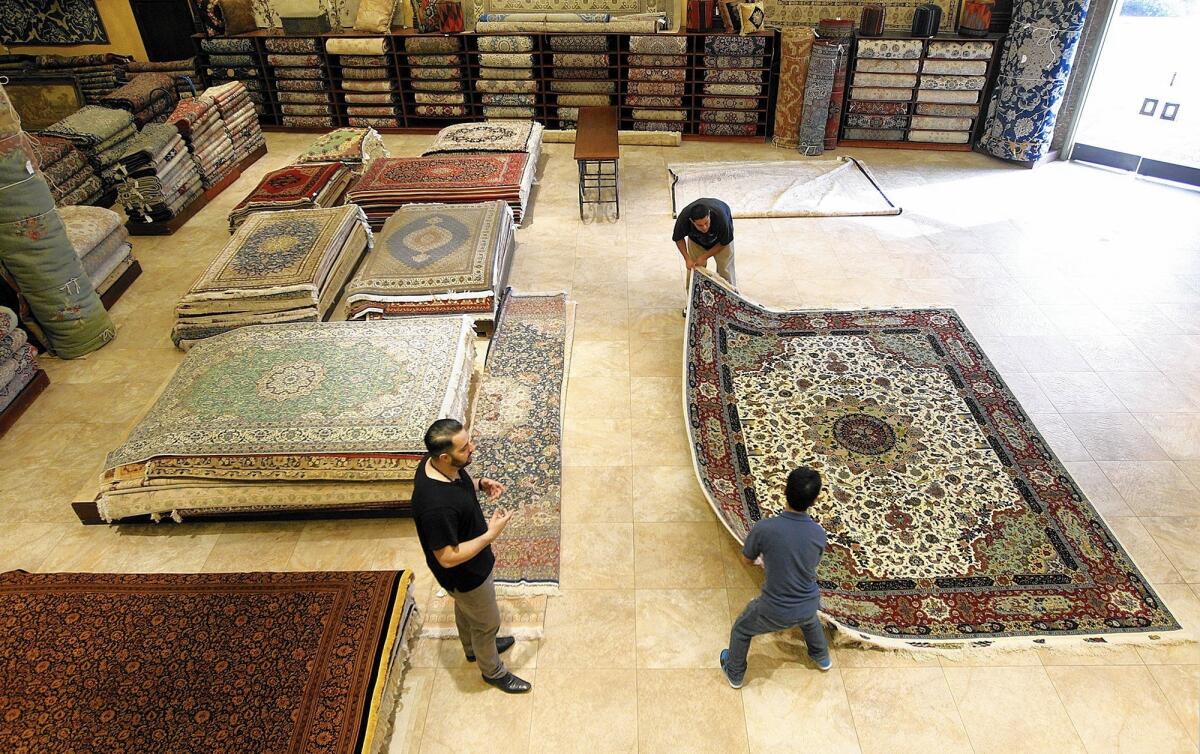

The earthy smell of silk and wool fills a showroom piled waist-high with thousands of hand-woven rugs, some of them centuries old. It is a familiar scent, one that links this Westwood shop to Tehran’s bazaars nearly 8,000 miles away.

Some of the carpets, dyed with natural ingredients such as walnut skins, pomegranate and acorn cups, took 10 years and five people to make, store owner Alex Helmi says.

Among his favorite pieces is a 9-foot ivory rug commissioned by Iran’s Ministry of Culture in the 1930s to honor the Persian poet Ferdowsi, whose poem “Shahnameh,” or “Book of Kings,” is considered the national epic of Iran. Archers ride on horseback across the carpet, their arrows aimed at deer frolicking through the silken forest.

For Helmi, the rug is a connection not only to his homeland but also to his cultural roots.

“We have been doing this for thousands of years,” Helmi says. “This is part of our history.”

But the Persian rug market has been a casualty of Iran’s recent history, and its chilly relationship with the United States.

A 2010 embargo on Iranian-made rugs has meant tough times for sellers such as Helmi, who found his carpets, some of them as featherweight as a down comforter, caught up in a clash of diplomats, geopolitics and nuclear brinkmanship. This summer’s landmark international nuclear agreement, however, has paved the way for importing rugs once again in what was once Iran’s largest foreign market.

“This is an art, not just an industry,” Helmi says. “To me, sanctioning an art is like saying don’t bring French paintings to America.”

A 2010 embargo on Iranian-made rugs has meant tough times for sellers who found their carpets caught up in a clash of diplomats, geopolitics and nuclear brinkmanship. This summer’s landmark international nuclear agreement, however, has paved the way

::

As a child in Tehran, Joseph Tizabi grew up playing with toys on rugs embroidered with silk flowers and eye-catching designs. Each room in his home had rugs in vibrant colors. On nights they would throw parties, they switched out their everyday rugs for more lavish ones.

“We’ve had Persian rugs in our house all my life,” he says as he unfurls a mustard-and-magenta rug in his Westwood living room.

When the supply of rugs dwindled and prices shot up during the embargo, many customers stopped buying high-end Persian rugs. But for Tizabi, their connection to his homeland — and childhood memories — was too strong to stay away.

The beauty of the rugs lies in “the talent and experience passed generation by generation,” Tizabi, 57, says.

For affluent collectors like Tizabi, the embargo has been a mixed bag. It has added value to the Persian rugs that they own, but they eagerly await its end so they can add to their collections.

“If you collect them, you don’t buy them for the value going up,” Tizabi says. “You buy it for the enjoyment of it.”

There’s a difference between the people of Iran and the government of Iran. The Persian rug is about talent. It has nothing to with a nuclear bomb.

— Alex Helmi, owner of Damoka rug shop

Tizabi circles the mustard carpet and inspects its coloring. Each step he takes reveals a different hue in the morning sun.

After the 1979 Iranian revolution, only two of his father’s rugs made it to Los Angeles. Tizabi has held on to those pieces, a pair of 150-year-old tapestries filled with flowers, trees and wildlife that he stores in the bedroom of his 17th-floor condominium.

He and his wife never sell their rugs, he says, although their collection is worth tens of thousands of dollars.

“This is part of our being,” he says. “Any Persian house you go in, they’ll have one. It’s something that’s within us.”

::

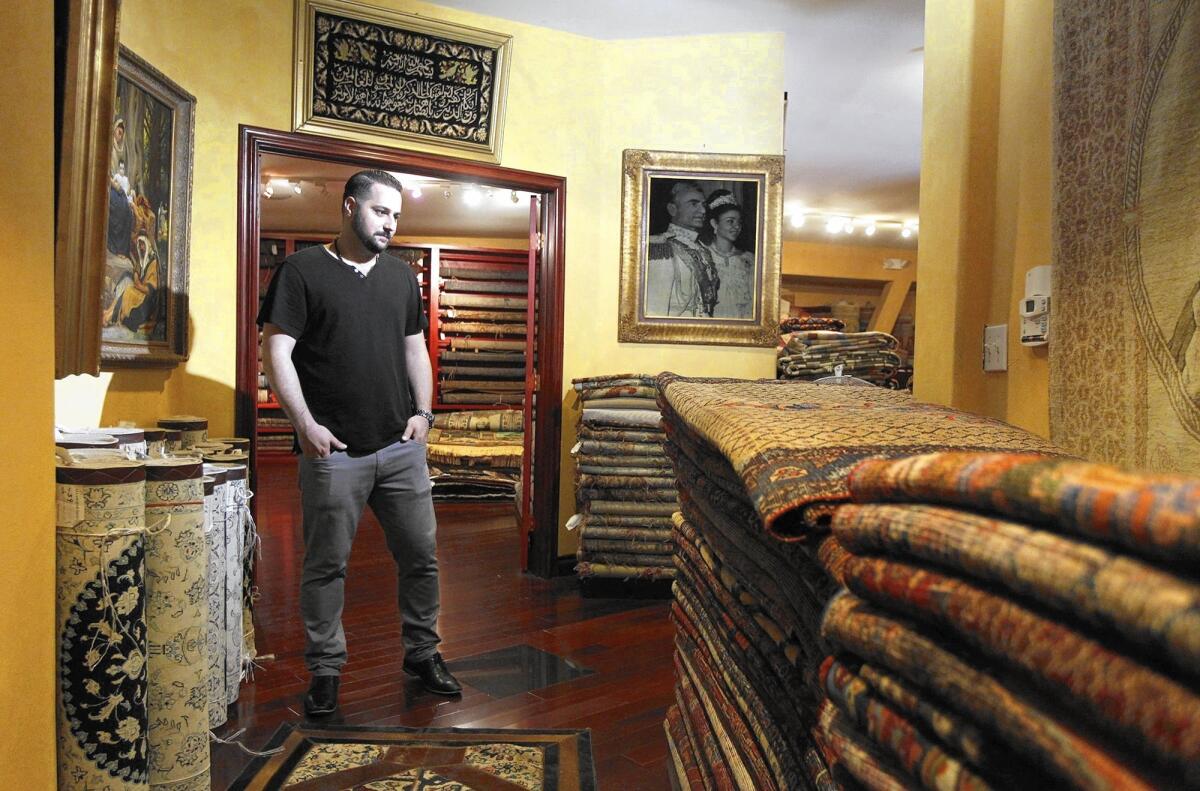

At Tousi Rugs in Westwood, Adel Tousi admires a threadbare russet carpet. Nearly 300 years old, the silk rug is a piece of Persian culture that has outlasted monarchies and revolutions.

“My grandfather bought it from a collector about 55 years ago,” Tousi says.

His family has been in the Persian rug industry for five generations, with galleries from Saudi Arabia to California.

“It’s all I know,” Tousi, 32, says. “I grew up in the business.”

At the height of their business, Tousi’s father would import hundreds — sometimes thousands — of rugs at a time, filling large shipping containers to the brim.

“In one shipment, he brought in 500 rugs and sold them within the same couple of weeks,” he says.

Apart from oil, Persian carpets were the product that suffered most from the sanctions. Experts say that before the embargo, the U.S. made up one-fifth of Iran’s carpet exports.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has said he expects sanctions to be lifted by the year’s end, but others say it could take six months. Before restrictions are lifted, Iran must dismantle parts of its nuclear facilities and reduce its uranium stockpiles under international supervision. If the U.S or any permanent member of the U.N. Security Council believes Iran has lied about its nuclear program, it will be able to demand a vote to end the suspension of sanctions.

For Tousi, the embargo has meant fewer sales, but it has also meant that those Persian rugs that do sell can fetch a much higher price. Some of Tousi’s rugs sell for more than $30,000, even as customers increasingly seek out more economical Afghan and Pakistani rugs.

“It’s hard to sell a Persian rug that’s more expensive to someone who doesn’t know the history of rugs, who doesn’t really care,” says Tousi, who runs the business with his father and brother.

Before the embargo, he says, dealers and collectors would come in every day. But like many dealers in an industry saddled by the sanctions, the Tousis have resorted to selling cheaper Middle Eastern rugs in order to stay afloat.

Otherwise, he says, “we would eventually have to go out of business.”

::

Helmi has also felt the pressure of cheaper rugs from other parts of Asia and the Middle East. Although customers at his store, Damoka, still buy Persian rugs, many others have turned to Indian or Pakistani rugs because their muted colors fit current trends.

“Business is OK,” he says. “Not great.”

The hardest part of the embargo is the inability to replenish his inventory, he adds.

“Not only can you not import a Persian rug, you can’t import an antique one that’s in France from 100 years ago,” he says.

Helmi says he is confident the nuclear accord will improve his business. Iranian collectors offered him $630,000 for a pair of rugs woven 60 years ago for the shah’s palace, he says, and the sanctions are the only reason he hasn’t entertained the offer.

One of the carpets hangs on the second floor of his gallery, its flowers of tan, red and blue illuminated by a spotlight overhead. Gazing at the glimmering rug, Helmi says he feels the way the weaver worked tirelessly on each knot. The embargo hurt weavers the most, he says, even though they don’t play a role in the complicated geopolitics behind the sanctions.

“There’s a difference between the people of Iran and the government of Iran,” he says. “The Persian rug is about talent. It has nothing to with a nuclear bomb.”

Downstairs, he points to a large rug hanging in the front of the store. A line scrawled at the top of in Persian reveals that the 140-year-old wool carpet once lay on the floors of Iran’s Congress.

Helmi situates himself on a pile of rugs, both legs dangling as he examines the piece. Its scarlet red has aged like a high-quality wine.

He pauses for a moment, then explains how thousands of years of art mingle with Iranians’ daily lives.

“We grew up on these rugs. As kids, we used to play on them, wrestle on them,” Helmi says. “It’s an emotional family tie.”

Twitter: @sarahparvini

MORE GREAT READS

For this drummer, no gig tops Griffith Park

Team of sleuths stalks cancer in L.A. County

A java man’s adventure in Japanese coffee roasting

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![LOS ANGELES, CA - JUNE 17: [Cody Ma and Misha Sesar share a few dishes from their Persian Restaurant Azizam] on Monday, June 17, 2024 in Los Angeles, CA. (Ethan Benavidez / For The Times)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/7ffc7f6/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5110x3417+306+0/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F79%2Fdc%2F4d29255545f5b9813315901692bc%2F1459972-fo-azizam-review20-eba.JPG)