Baddest bear in town

- Share via

MAMMOTH LAKES — The two break-in artists were caught in the act. Steve Searles had them cornered right outside the crime scene, high in the branches of a towering Jeffrey pine.

“Bad bears!” he growled up at the 100-pound cubs, who peered back innocently. “What are you guys doing? Who do you think you are?”

The yearlings had followed their mother through an open back window into an unattended condominium, where they’d ransacked the kitchen and living room, scattering packages of flour, pasta and honey crackers. They had jumped on the bed, mangled some wooden blinds and left a smelly calling card on the carpet. Then Mom had taken off, leaving the cubs on their own.

A witness contacted police. They called Searles -- known here as the man who talks to bears.

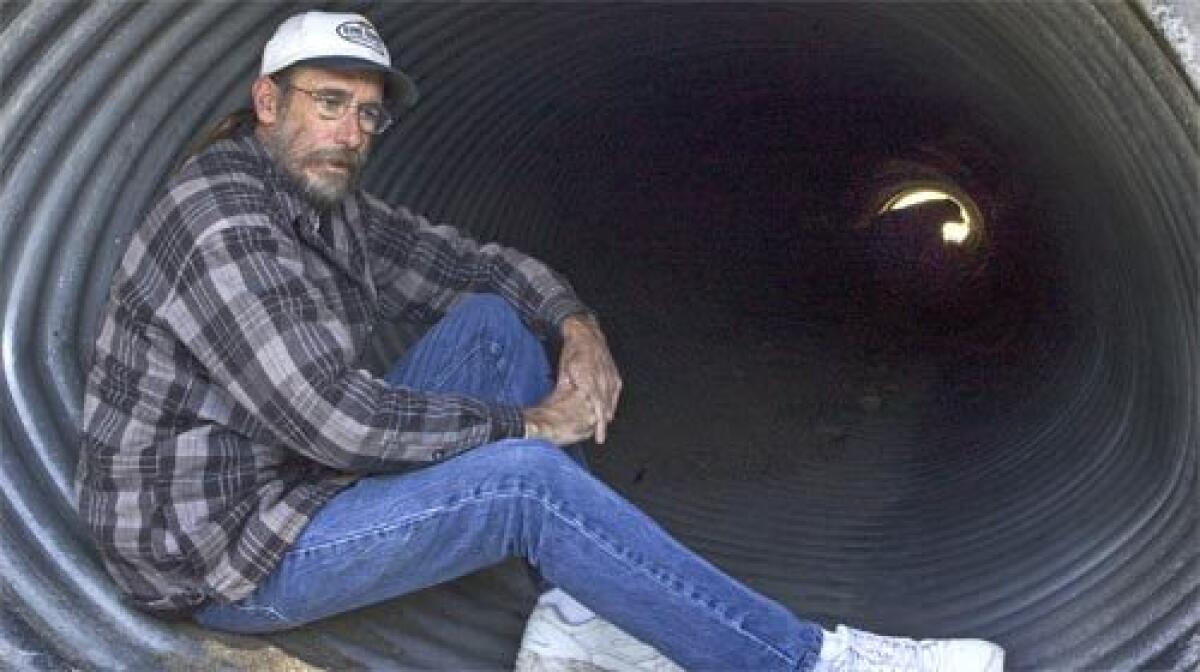

Bearded and lanky, his graying ponytail tucked under an ever-present baseball cap, the eccentric former hunter and high school dropout contemplated his next move.

At one time, before the Orange County native began his work with the three dozen resident bears in this eastern Sierra tourist town, the cubs would have been trapped or shot with a tranquilizer gun -- or maybe just shot, period.

Searles uses different tools: firecrackers and flares, rubber bullets, air horns -- all nonlethal techniques he refers to as “bear spankings.” It’s his version of ursine tough love.

“Steve gets along fine with the bears,” said George Shirk, editor of the local Mammoth Monthly. “It’s people he sometimes has a problem with.”

Since he became the Police Department’s volunteer wildlife specialist in 1996, Searles has gained a national reputation as a bear whisperer, someone who can deal with problem bears without killing them.

He tries to think like a bear. He studies their habits and social hierarchy. He has participated in Native American ceremonies to learn what the tribes perceive as bears’ spiritual nature. He even has been known to spread his own urine to drive away territorial animals.

“I’m the biggest, baddest, meanest bear in this town -- that’s what I want them to think,” said the 48-year-old. “I’m the alpha male, and they must obey me.”

California Department of Fish and Game officials are dubious. Searles’ methods, they say, do not alter behavior but merely encourage animals to move to other locations.

Wardens and biologists insist that bears who habitually raid homes for food or shelter -- especially those who threaten humans -- cross a well-demarcated line and must be put down.

Each year about 100 problem black bears are killed in California, most of them by game wardens, law enforcement officers and property owners carrying a special permit. No permits have been issued in Mammoth Lakes since 2000, and usually about one bear a year is put down as a public safety hazard, officials say.

Though the animals have been known to attack humans, no one has been killed by a black bear in California, Searles says. He insists that his message to residents about coexistence is one reason no one has applied for a special permit in recent years.

“People are getting the message,” he said. “They used to ask for permits to take down problem bears, because it was the only answer: You could either put up with them or kill them. There was no middle ground before.”

His approach is in sync with a town that celebrates the bears in its midst -- where a handful of shops and restaurants feature wooden bear statues and some golf course sand traps are shaped like bear paws.

Searles does have to kill bears when they are hit by cars, which happens often. It is his grimmest task, he says. He’s never killed a bear for public safety reasons but insists he’d be capable of pulling the trigger in the right circumstance: “If I found a Jeffrey Dahmer bear that would eat someone, I’d blow his head off in a nanosecond.” But with behaving bears, Searles speaks in a singsong Mister Rogers voice. “Hi, sweetie,” he’ll say.

With only a ninth-grade education, he has shared his methods at scientific conferences and trained law enforcement in New Jersey, Minnesota and Canada. He has counseled rangers in Yosemite National Park. “Here are these people with their advanced degrees watching this high school dropout draw national attention,” Shirk said. “Steve’s a rebel. He does things his own way.”

Searles and his bosses don’t always see eye to eye. This spring, he was fired by Mammoth police who said he was not notifying dispatchers of his whereabouts. Searles insists the termination was political.

In September, the Police Department returned Searles to his job after residents spoke out at an emotional Town Council meeting. Many in the standing-room-only crowd said the bear problem had worsened in his absence. They wanted him back, and right away.

“Steve’s not a guy who likes to be called a hero, but that’s what he is,” resident Dave Tidwell said to applause. “He’s a nationally recognized bear specialist, right here in our town. And we want him back.”

Such adulation surprises Searles. “I’m just a dopey guy who was the least likely to succeed in school,” he said. “But these bears are important to this town. And to me.”

Searles arrived in Mammoth Lakes from Newport Beach in 1976. He survived on odd jobs, such as carpentry and towing cars. Then he became one of the area’s most successful hunters and trappers. “I was a good killer,” he said, adding: “Learning an animal and its habits, outwitting the smartest creature, was incredibly satisfying.”

In the early 1990s, then-Mammoth Lakes Police Chief Michael Donnelly asked Searles to help cull a rampant coyote population. He killed 43 animals in six months, singling out the alpha male first.

The experience changed him, he said. He grew weary of the bloodletting. Hunting began to repulse him.

In 1996, Donnelly asked him to turn his attention to nuisance black bears, who were raiding ice cream shops, traipsing through cabins, sauntering down Main Street. Searles said he needed time to study the animals’ habits.

From the safety of an elevated deck, he watched bears forage through restaurant Dumpsters and was awed by their agility and intelligence. He watched them ease themselves along narrow railings like 500-pound gymnasts. He saw a bear elegantly remove the top of a mayonnaise jar, another pick the lock of a secured trash bin.

“Those bears captured me,” he said. “There was no sense of one-upmanship or revenge. For the bears, there was nothing to prove. They were just a bunch of graceful, powerful creatures.”

Searles began assigning them handles. George and Junior, Bertha, Brownie, Yogi, One Ear, Ace -- and one particularly nettlesome bear he called Hemorrhoid.

One night, he saw several bears scatter as a male named Big strutted by, “moving in like some big weightlifter.” Searles had an epiphany: “I had to become Big. I had to instill fear in the other bears.”

His nighttime stakeouts taught him something else: In a town with more than 450 Dumpsters, some restaurants purposely left trash receptacles open, advertising evenings of food and bear watching. Tourists also left out food to attract hungry bears.

“We had a people problem,” Searles said, “not a bear problem.”

Searles pitched Donnelly an alternative plan: Rather than shooting the bears, he suggested an education program for humans and animals alike. Lock down Dumpsters. Fine restaurants for mishandling trash. Teach bears that human food is off-limits. Show residents how to scare off bears so they wouldn’t feel the need to use lethal force. He circulated his cell phone number: 937-BEAR.

“Steve’s ideas may have been uncouth -- to say they were out of the box is an understatement,” Donnelly said. “But they were things Fish and Game or nobody else had ever suggested.”

The chief brought Searles onto the force as a volunteer, issued him a badge and instructed him to train officers in bear hazing techniques. His “Bear-Be-Gone” kits included flash grenades and pyrotechnics, as well as shotgun shells in case the bear’s response threatened to turn deadly.

One day, he saw One Ear walking across a crowded elementary school playground. As children watched, Searles chased off the 450-pound animal with a few rubber bullets to the rump.

“What could have been a nightmarish kill scene became a learning experience in nonviolence,” he said. “The kids said I spanked the bear.”

But state officials remained suspicious.

Al Zamudio, a former Fish and Game warden, said his supervisors assigned him to watch Searles. “I spent a lot of nights following Steve,” Zamudio said. “My lieutenant told me to keep an eye on him. If I caught him doing anything illegal, he said he’d buy me a steak dinner.”

Zamudio reported that Searles was actually saving the agency work. “They waved me off. To them, Steve was a wacko who didn’t know what he was doing,” he said.

Asked about the surveillance, Fish and Game spokesman Steve Martarano would say only: “If there’s suspicion of a crime, we’ll use it. It’s how we catch poachers in the wild.”

In March, new Mammoth Lakes Police Chief Randy Schienle relieved Searles of his volunteer job, citing his performance.

Searles says the firing came because he was outspoken about the town’s problems. He handed out bumper stickers that read “Mammoth, Not Mammeth: Locals Against Crime,” his call to action against area drug use.

“It hurt to give back that badge,” he recalled. “It was just ceremonial, but to me it felt like the diploma I never got.”

In August, state officials killed a bear after it had entered several cabins, some occupied, at a lake near town. The shooting angered residents, and the Town Council invited a state Fish and Game warden to restate the agency’s bear policies.

At the September meeting, a dozen residents called for Searles’ return. “Bring him back,” said resident Doug Schneider. “He’s our bear whisperer.”

The Town Council promised to study the request. Several nights later, a bear was hit by a car and critically injured near downtown. Searles drove by the scene with his wife, Debra, and 8-year-old son, Tyler. They sat in the truck and cried, watching the paralyzed bear lift its head, roaring in agony.

“I told Steve to get out and put the bear down, we just couldn’t stand to watch it suffer,” Debra Searles said. Then Searles got the call: a police dispatcher asking him to respond. “I’m already here,” he said.

Police euthanized the bear as Searles soothed passersby. “Given the number of bear incidents, it made sense to authorize the police to bring Steve back,” said Town Manager Rob Clark.

“People here trust him to deal with bears humanely.”

Searles said he’s glad to be back.

He knows the town’s bears have relearned some bad habits. So he plans to go slowly.

“It’s like a parent coming home after a vacation to find the kids running wild,” he said. “I’m not going to lose my cool right away.”

That was good news for the cubs Searles had treed near the ransacked condo. He left them with a stern lecture. “No more of that, you naughty little bears.”

Then he turned and whispered, “Cute, aren’t they?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.