A new Cyclone Racer for Long Beach? It’s a long shot

A Downey man who spent years painstakingly researching the details of the fabled ride has roller-coaster-high hopes for a rebuild.

- Share via

Larry Osterhoudt lives alone in the Downey house where he grew up, a neat, single-story that still wears the same faded pink and white lace curtains with a kind of quiet pride.

An elaborate Lionel train set takes up much of a bedroom-turned-office, and an old, poster-sized aerial photograph of Disneyland hangs above it on the wall.

A midnight blue '79 Pontiac Trans Am, the first brand-new car Osterhoudt bought at 22, sits idle in the garage.

"I always like to reminisce about my past," the 57-year-old says. "People think I'm crazy about it sometimes. That I remember a little too much detail."

Details are like a narcotic to Osterhoudt.

He doesn't just remember watching "Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color" when he was a kid — he knows it was on at 7:30 p.m., Sundays, Channel 4. He knows it was a Thursday in the summer of '68 when his family hit the road for a vacation in Yosemite, where the waterfalls that year were just a thin trickle.

And he knows it was a Saturday two summers earlier when his parents piled him and his three brothers and sisters into their powder-blue Buick and headed to the beachfront amusement park called the Pike.

It was a rare treat for the working-class family from Downey — the closest Osterhoudt had come to experiencing an amusement park was the dime-a-ride electric horse in front of the local supermarket.

He followed his father to the double Ferris wheel, which swung and swayed in dizzying loops over the water's edge. He clung to the safety bar, growing queasier by the minute.

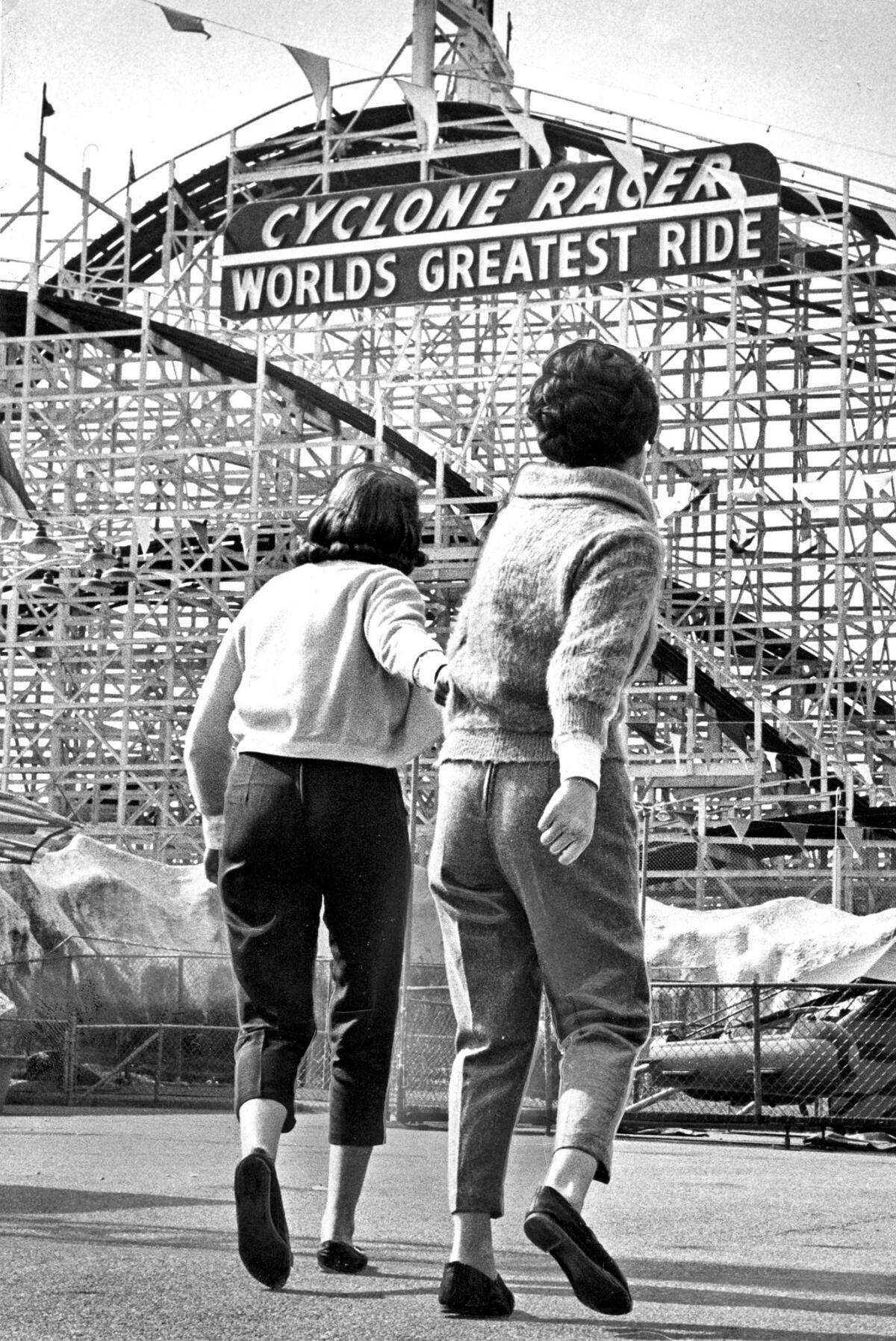

The iconic thrill ride in 1961. (Los Angeles Times) More photos

Then his father pointed to the roller coaster. Osterhoudt peered at the whitewashed wooden facade towering 100 feet over him. The screams from the riders pierced the salty air. The Cyclone Racer, with its dual tracks, hairpin turns and skeletal frame dangling over the ocean, terrified the 9-year-old.

So they left the Pike and never went back. Two years later, after nearly four decades on the Long Beach boardwalk, "The World's Greatest Ride" closed for good.

He had missed his chance to ride the beast that was the Cyclone Racer.

Osterhoudt's workshop, set in a shed behind his house, is littered with technological anachronisms — rainbows of electric wiring wound tight around dowels, VHS players — all plugged in — stacked on shelves and an army of miniature tube televisions, remnants of his time as an electrical repair technician at Panasonic.

On the job at Panasonic, he remembers being the one who could coax stubborn tape decks back to life and salvage machines that others regarded as lost causes.

But when the company moved to Colton, 50 miles away, he stayed behind.

"I'm just used to this," he says. "This is my home. I can't move."

He made money repairing VHS players until DVDs rendered his services obsolete, and then tried his hand as an inventor — an applause-o-meter and a guitar pedal he swore could replicate the sounds of the Eagles' "Hotel California."

There I was, 9 years old, looking up at that big monster again.”— Larry Osterhoudt

None of them took off.

One day, Osterhoudt was chatting with a buddy at the gym, recounting a recent trip to Disneyland. A friend had gone ash-white riding the Matterhorn.

"That's nothing!" the gym buddy replied. "He would have gone crazy on the Cyclone Racer."

Suddenly, Osterhoudt was hurled back to his childhood and the trip to the Pike.

"There I was, 9 years old, looking up at that big monster again."

He began chasing a memory.

Osterhoudt couldn't stop thinking about the beast that had defeated him. He turned that moment over in his mind again and again, until, finally, he started digging.

A photo obtained by The Times in 1988 shows the Cyclone Racer at the Pike in Long Beach in the 1930s. More photos

He pulled the coaster's patents at the library. He visited the historical society in Long Beach and scoured online auctions in search of signs, memorabilia, any remnants of the ride's past glory. After discovering that the blueprints had been destroyed, he began drawing the coaster by hand and later with a computer drafting program.

By studying photographs he pieced together the ride's dimensions, the degree of every banking, the swoop of every turn, careful to account for the way a camera lens warped dimensions.

With the photos mounted and magnified on his television screen, he looked past black-and-white smiles and bathing beauties — all useless to him. Behind them were more vital clues: how many planks to the highest point, how many supports under each curve.

One photo showed the old coaster in the distance behind the Looff Carousel building. Armed with a clipboard and tape measure, Osterhoudt and his brother measured the building, still standing in 1997, by then a Lite-a-Line bingo parlor. From that, he calculated the coaster's length.

"I have the knowledge to put Humpty Dumpty back together again," Osterhoudt says with a bullish confidence, "no matter what."

When he could sketch no more, Osterhoudt turned to building. He spent thousands of dollars on glue and basswood, building a scale model of the ride's towering entrance. Each tiny board was laid just so, and in a forest of X-braces, Osterhoudt managed to find design anomalies and replicate each one.

No detail was too small. A large hand-painted sign hanging in Osterhoudt's living room displaying the ride's slogan retains what were surely inadvertent flaws in the original lettering — a space from a missed brush stroke, an odd squiggle in place of the straightedge.

Tallies on a white board mark the hours he spent painting each letter — three hours for the "R" in racer, two on the "A."

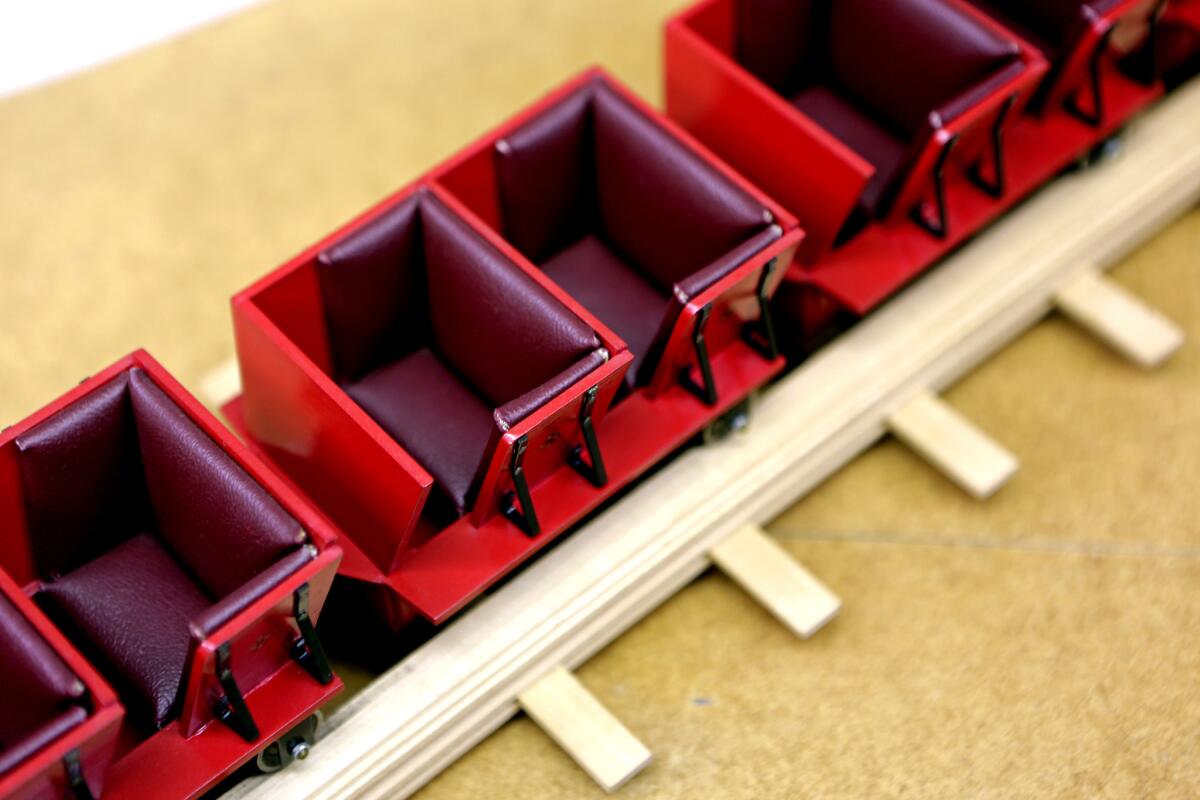

Osterhoudt's scale models of the Cyclone Racer's cars, which he was finally able to study after persuading an antiques collector who owned one to give him access. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Still, something was missing. Osterhoudt still didn't have pictures of the Cyclone Racer's dueling cars up close. He was stuck.

He was stunned when the historical society announced it would display the last known Cyclone Racer car in its museum for several months. The treasure, culled from a local dump, belonged to an antiques collector.

Osterhoudt showed up with tape measure, pen and pad in hand.

He spent three days a week at the museum, open to close, measuring and recording every inch of the artifact.

Still, it wasn't enough — he had to get inside the wheels, see what made them run. But the owner, Ken Larkey, was wary. Osterhoudt spent eight years wooing him — fixing his TV and record player — until Larkey finally relented.

Larkey has since died, but Osterhoudt still credits him — and fate — with helping him find the last missing piece of the puzzle.

"It's like some strange power was controlling the whole thing," he says of his quest.

The grand entrance to the Cyclone Racer reared up in Osterhoudt's workshop — nearly 5 feet tall, 8 feet from end to end, a precise scale model of the monster he had seen as a child.

When that was complete, he took to wearing a custom-printed T-shirt with the Cyclone Racer's logo and handed out business cards listing him as "Project Designer." He called the Cyclone Racer the "eighth wonder of the world" and talked about it in the same breath as the Hoover Dam and the Golden Gate Bridge.

But aside from the occasional call from a nostalgic baby boomer, it appeared his 17 years of obsessive labor had been but a lonely indulgence.

Then, one day in October, Long Beach City Councilwoman Gerrie Schipske called him up. Would he be interested in rebuilding the Cyclone Racer — not a model, but the real thing?

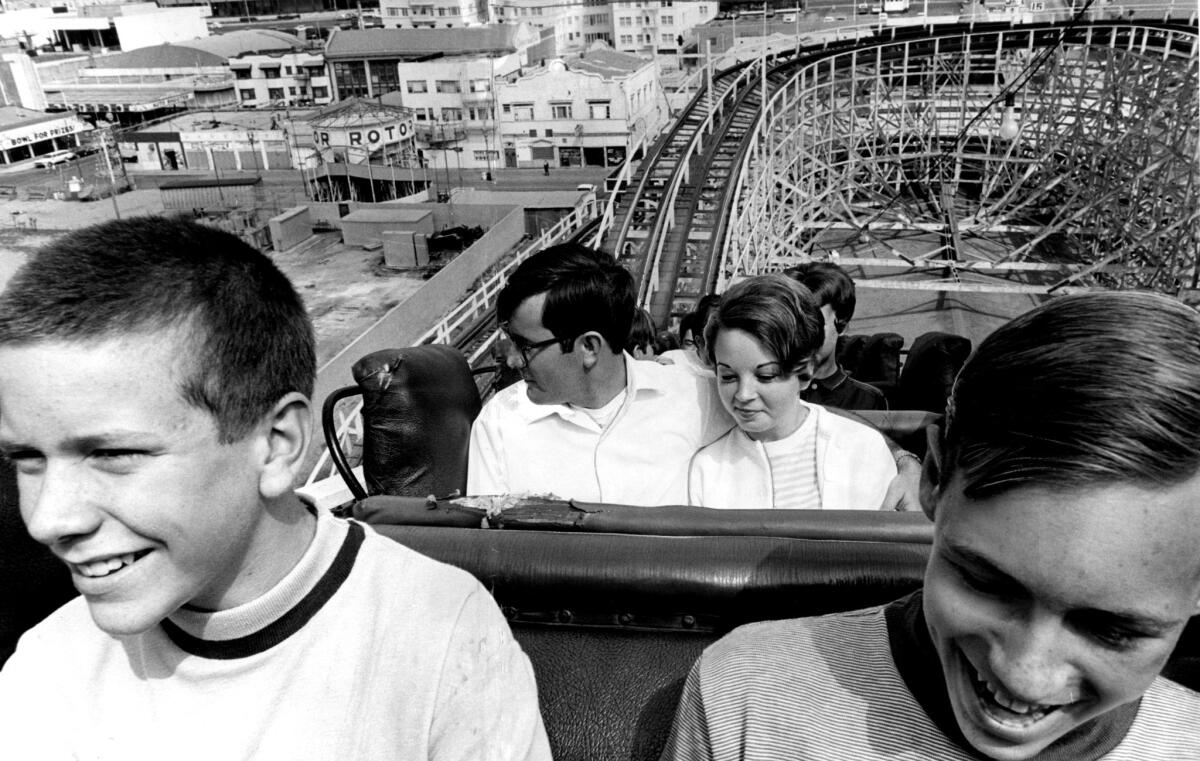

Thrill-seekers enjoy a final ride on the Cyclone Racer on its last day of operation, Sept. 15, 1968. The ride was later torn down. (Los Angeles Times) More photos

She told him it could be a novel way to bring tourism dollars to the struggling waterfront. She promised to bring the issue before the council and asked him to speak at a community meeting to answer questions and drum up support.

"This was supposed to be the king of roller coasters," Schipske says of the Cyclone Racer. "I liked the thought of revisiting something that played such a big part in Long Beach history."

When the local media reported that the coaster could be on the verge of an epic comeback, Osterhoudt's phone began to ring. Message boards and Facebook threads were alight at the prospect of bringing the Cyclone Racer back.

The City Council voted to move forward with a feasibility study on the concept, asking staff to examine possible locations.

But much remains unclear.

The locations Osterhoudt has discussed, on a pier below Shoreline Park, or in the park itself, would require approval from as many as half a dozen state and federal agencies, and a third location next to the Queen Mary is owned by a developer whose lease runs until 2061.

Once you ride it, you're gonna know exactly what I'm talking about.”— Larry Osterhoudt

Lengthy environmental studies would also have to be ordered, and not every politician in town is sold on the idea.

"I wonder are we really getting people's hopes up for something that I think is unlikely to happen," Councilman James Johnson said, adding that the city should be focused more on shoring up the police force and restoring cut services.

None of that deters Osterhoudt, who says he has already recruited an investor, though so far he's kept the funder's identity secret.

"Once you ride it, you're gonna know exactly what I'm talking about," he says excitedly, forgetting perhaps that he's never actually ridden the Cyclone Racer.

The feasibility report left the ball in Osterhoudt's court — the city says it has yet to receive a formal proposal from him or the purported investor.

Osterhoudt promises it's coming.

"When you work for something for 17 years, it just becomes a part of you," he says. "I won't give up on it until I die."

Or, he adds, until he can finally climb aboard and take his first, sweet ride.

FOR THE RECORD:

Cyclone Racer: An article in the March 25 Section A about a man's hope of rebuilding the Cyclone Racer roller coaster in Long Beach said that Larry Osterhoudt pulled the ride's patents at the library. According to Osterhoudt, he pulled patents for technology that predated the roller coaster, but that was later adapted and used to build the Cyclone Racer. —

Follow Christine Mai-Duc(@cmaiduc) on Twitter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.