Spitting in the eye of mainstream education

- Share via

Reporting from Oakland — Not many schools in California recruit teachers with language like this: “We are looking for hard working people who believe in free market capitalism. . . . Multicultural specialists, ultra liberal zealots and college-tainted oppression liberators need not apply.”

That, it turns out, is just the beginning of the ways in which American Indian Public Charter and its two sibling schools spit in the eye of mainstream education. These small, no-frills, independent public schools in the hardscrabble flats of Oakland sometimes seem like creations of television’s “Colbert Report.” They mock liberal orthodoxy with such zeal that it can seem like a parody.

School administrators take pride in their record of frequently firing teachers they consider to be underperforming. Unions are embraced with the same warmth accorded “self-esteem experts, panhandlers, drug dealers and those snapping turtles who refuse to put forth their best effort,” to quote the school’s website.

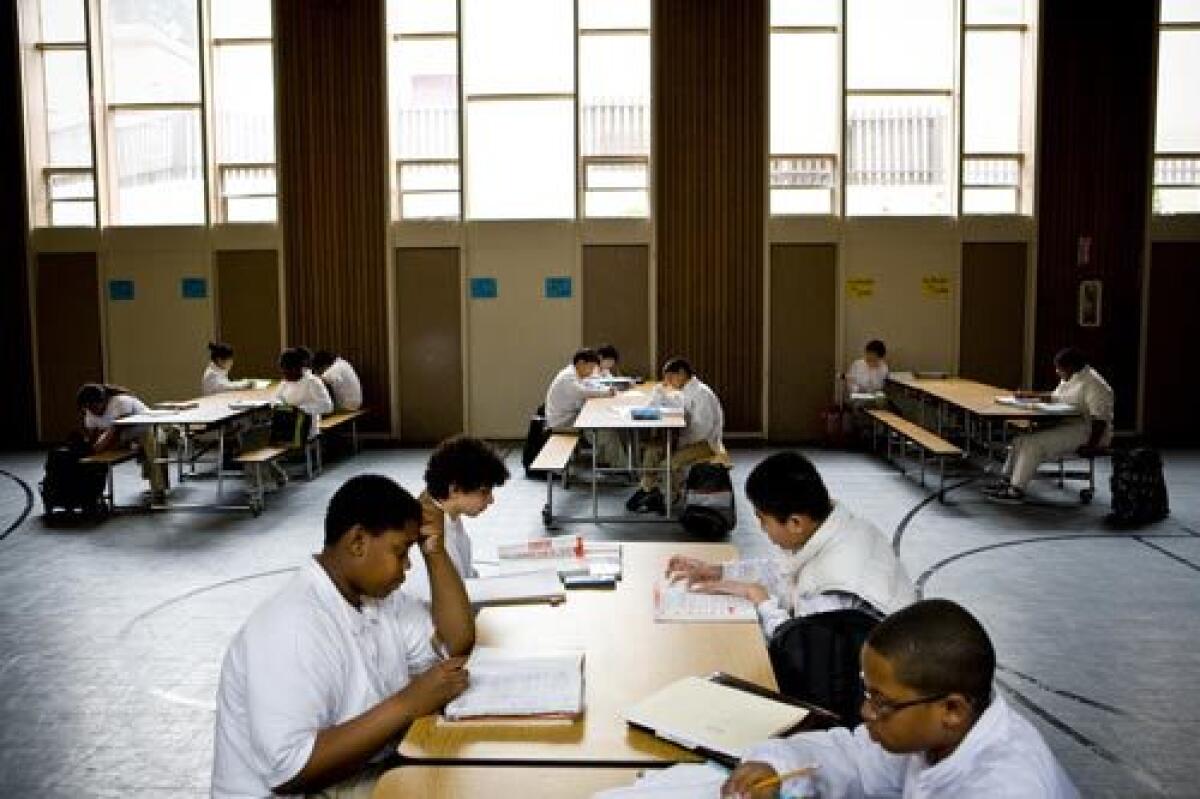

Students, almost all poor, wear uniforms and are subject to disciplinary procedures redolent of military school. One local school district official was horrified to learn that a girl was forced to clean the boys’ restroom as punishment.

Conservatives, including columnist George Will, adore the American Indian schools, which they see as models of a “new paternalism” that could close the gap between the haves and have-nots in American education. Not surprisingly, many Bay Area liberals have a hard time embracing an educational philosophy that proudly proclaims that it “does not preach or subscribe to the demagoguery of tolerance.”

It would be easy to dismiss American Indian as one of the nuttier offshoots of the fast-growing charter school movement, which allows schools to receive public funding but operate outside of day-to-day district oversight. But the schools command attention for one very simple reason: By standard measures, they are among the very best in California.

The Academic Performance Index, the central measuring tool for California schools, rates schools on a scale from zero to 1,000, based on standardized test scores. The state target is an API of 800. The statewide average for middle and high schools is below 750. For schools with mostly low-income students, it is around 650.

The oldest of the American Indian schools, the middle school known simply as American Indian Public Charter School, has an API of 967. Its two siblings -- American Indian Public Charter School II (also a middle school) and American Indian Public High School -- are not far behind.

Among the thousands of public schools in California, only four middle schools and three high schools score higher. None of them serves mostly underprivileged children.

At American Indian, the largest ethnic group is Asian, followed by Latinos and African Americans. Some of the schools’ critics contend that high-scoring Asian Americans are driving the test scores, but blacks and Latinos do roughly as well -- in fact, better on some tests.

That makes American Indian a rarity in American education, defying the axiom that poor black and Latino children will lag behind others in school.

First graduates

On Tuesday, American Indian’s high school will graduate its first senior class. All 18 students plan to attend college in the fall, 10 at various UC campuses, one at MIT and one at Cornell.

“They really should be the model for public education in the state of California,” said Debra England of the Koret Foundation, a Bay Area group that has given more than $100,000 in grants to American Indian. “What I will never understand is why the world is not beating a path to their door to benchmark them, learn from them and replicate what they are doing.”

So what are they doing?

The short answer is that American Indian attracts academically motivated students, relentlessly (and unapologetically) teaches to the test, wrings more seat time out of every school day, hires smart young teachers, demands near-perfect attendance, piles on the homework, refuses to promote struggling students to the next grade and keeps discipline so tight that there are no distractions or disruptions. Summer school is required.

Back to basics, squared.

There is no secret to any of this. Portions of the American Indian model resemble methods used by the KIPP charter schools or, for that matter, urban parochial schools.

“What we’re doing is so easy,” said Ben Chavis, the man who created the school’s success and personifies its ethos, especially in its more outrageous manifestations. (One example: He tends to call all nonwhite students, including African Americans, “darkies.”) Although he retired in 2007, Chavis remains a presence at the school.

A Lumbee Indian who grew up poor in North Carolina and later struck it rich in real estate, Chavis took over American Indian in 2000, four years after it was founded with a Native American theme.

He began by firing most of the school’s staff and shucking the Native American cultural content (“basket weaving,” he scoffed). “You think the Jews and the Chinese are dumb enough to ask the public school to teach them their culture?” he asks -- a typical Chavis question, delivered with eyes wide and voice pitched high in comic outrage. There is no basket weaving at American Indian now -- and little else that won’t directly affect standardized test scores. “I don’t see it as teaching to the test,” said Carey Blakely, a former teacher at the school who is writing a book about it. “I see it as, there are certain skills and knowledge that you’re supposed to impart to your students, and the test measures whether your students have acquired those skills and that knowledge.”

In Lindsay Zika’s eighth-grade classroom, the day begins precisely at 8:30, when, without prompting, her students recite the American Indian credo:

“The Family,” they chant. “We are a family at AIPHS.”

“The Goal: We are always working for academic and social excellence.

“The Faith: We will prosper by focusing and working toward our goals.

“The Journey: We will go forward, continue working and remember we will always be part of the AIPHS family.”

They recite this in a slightly robotic monotone. With barely a pause, they shift to the school’s mission statement, which is twice as long and includes the promise that American Indian will develop students to be “productive members in a free market capitalist society.”

To the test

Another day begins.

Zika starts with some comments about a recent history project, “Civil War for Dummies,” in which the students wrote primers on the Civil War.

“These are very well done,” she tells the class. “They’re fabulous to read . . . and they show that you guys understand the Civil War incredibly well.”

She moves to spelling. The students, seated in old-fashioned lift-top desks in tight rows, pull out work sheets. Zika selects a shy girl, Alexandria Lai, to lead a drill in which she says a word and others spell it.

Zika is dressed in business attire: black glasses, black skirt, black wool overcoat, her blond hair in a ponytail. She is the quintessential American Indian teacher: young (26), well-educated (Notre Dame, Oxford), self-confident, mature. A product of Oakland Catholic schools, she is warm yet reserved, with an underlying sternness. “I think kids want structure,” she says. “They want strict teachers.”

By eighth grade, discipline is not really an issue. Classes are preternaturally quiet and focused. Visitors may be startled to notice that students do not so much as glance at them. They have been told to keep their attention on their work. They do as they are told.

Students who misbehave in the slightest must stay for an hour after school; if they misbehave again in the same week, they have more after-school detention plus four hours of Saturday detention.

Under Chavis, the school also relied on humiliation to keep students in line, ridiculing miscreants and sometimes forcing them to wear embarrassing signs. When one boy was caught stealing, Chavis shaved his head in front of the entire school. (The boy, Jeremy Shiv, now a straight-A student at American Indian High, considers what Chavis did “pretty cruel.”)

A framed poster in a hallway quotes Chavis: “You do outstanding things here and you’ll be treated outstanding. You act like a fool and you’ll be treated like one.”

That concept isn’t dead at American Indian, but it has been toned down.

All American Indian students have 90 minutes of English and 90 minutes of math a day.

The grammar lesson today focuses on appositives, nouns that modify other nouns. Student Isa Bey is asked to write an example on the board.

“The extreme abolitionist John Smith was hung after a brutal revolt,” he writes.

Zika smiles. “Historically, there’s a problem,” she says. “Grammatically, it’s correct.” Chagrined, Isa erases “Smith” and writes “Brown.”

“I like that he’s connecting it historically,” Zika tells the class, “but let’s get it correct.”

At 10:05 a.m., the students switch to math. The move takes about 10 seconds.

American Indian’s administrators believe that one of the secrets to success in middle school is having one instructor teach all subjects except physical education. The goal is to have that teacher stay with the same children all three years -- a policy that seems to be more theory than reality, given high teacher turnover.

Time saver

The idea is that students will form a deep bond with the teacher and gain class time by having no passing periods. “We really see things in terms of minutes,” said principal Janet Roberts, who took over from Chavis.

Five minutes per passing period might not sound like much, but over the course of a year, American Indian saves the equivalent of more than a week’s worth of instruction.

Math class begins with a warmup exercise to get students thinking numerically. Then the class goes over the previous night’s homework and moves to new material.

All students at American Indian take Algebra 1 in eighth grade, and the school prides itself on its math achievement. Last year, every eighth grader scored “proficient” or better on California’s state algebra test. Statewide, only half the eighth graders even took algebra and fewer than half of those scored “proficient” or better.

Today’s lesson is Chapter 14: probability.

“What is probability?” Zika begins. “Rebecca?”

“The chance you have of getting something,” Rebecca says.

“Yeah,” Zika says. “This is an important skill in life.”

Zika displays a confidence in math that is rare for someone who majored in political science. “I like teaching math the best,” she says.

They move on to factorials, and before long, Zika has the students doing rapid-fire exercises in which she gives them a number and they figure out its factorial on a whiteboard and hold it up for her to see. (A factorial is the product of all positive integers less than or equal to a given number.) The students are generally correct and seem enthralled.

One of the most common questions about charter schools is whether they “cherry pick” the best students and most motivated families.

Charters are required to take all applicants -- or, if they have more students than seats, to hold a lottery. American Indian has never done this and was denied a charter to open a new school last fall in part because school district officials said administrators were “unable to describe” the selection process.

Roberts and Chavis say they have never had more applicants than seats, so they never held a lottery. They also say that they attract a representative sample of students from local elementary schools.

But Ron Smith, the principal of nearby Laurel Elementary, who sent both of his own children to American Indian, says that’s not the case for students from his school.

Of those who go from Laurel to American Indian, “I’d say 70% are academically strong, and 30% are a cross-section. . . . They have kids who I know could go anyplace in the state and succeed.”

The school could not provide its students’ elementary school test scores, so it is hard to say if they were above average. Roberts did provide three years of middle school scores for all students who entered American Indian in 2004 (with names removed for privacy), showing their progress in math and English from sixth to eighth grade. Of the 51 students who entered American Indian’s middle school that year, only six scored lower than “proficient” in both math and English at the end of sixth grade.

It’s impossible to tell whether the students were academically strong at the start of sixth grade or were brought up to grade level by the rigors of a year at American Indian.

Of the six who scored below “proficient,” three left the school and the remaining three showed some progress by the end of eighth grade.

It isn’t clear why the students left. American Indian insists that it has never expelled a child but says some leave because their families move or decide the school is a poor fit. Of the 51 students who made it through their first year, 39 finished.

“They’ve had a reputation among the local public schools as being very interested in kind of recruiting kids who are going to do well, and getting rid of kids who won’t,” said Betty Olson-Jones, president of the Oakland Education Assn., the teachers union. Both Chavis and Roberts strongly deny this and say their method works with all children. “Give me the worst middle school in America and let us run it,” said Chavis. “I guarantee it will improve.”

When math ends at 11:40, Zika switches to science. With no lab equipment and an emphasis on textbook learning, it is hard to imagine that American Indian will turn out the next Darwin or Edison. The students have brought in paper towel tubes and, after a discussion of the American space program, Zika leads the class outside, where they have about five minutes for a rare experiment: making rockets. It doesn’t go well. With so little time, the experiment more or less fizzles, and then it’s lunch. Zika admits it was a mistake; the next day, she’ll have the students discuss what went wrong and try again.

After lunch, it’s history (Reconstruction and its legacy), and then preparation for a philosophical debate. “Isa, how do you know you’re really sitting here? How do you know you’re not a brain in a dish hooked up to a machine?” Zika asks.

“I am because I think I am,” pipes up Terae Collins, paraphrasing Descartes.

This is as fun as it gets.

At 2:10, the students have P.E. -- running and calisthenics. No games.

The class returns at 2:50 for some last-minute homework instructions. School ends at 3. Most stay and do homework until 4 -- just because they can.

A face appears at the door. It is De-Zhon Grace, a boy who was in Zika’s class until Barack Obama was inaugurated as president.

Until then, De-Zhon and his mother had been fairly happy with American Indian. “I’m a single mom, and I’m trying to raise an African American young man, and I’m very serious about his education,” said Chaka Grace.

But on Jan. 20, De-Zhon stayed home to watch the inauguration with his extended family. And that crossed a line for Roberts, who believes that nothing -- absolutely nothing -- should get in the way of class. According to De-Zhon’s mother, Roberts said the boy would receive extra work as punishment and that she might rescind his recommendation to a private high school.

That, said Grace, “took it to another level for me. . . . I felt that was evil.” She pulled her son out of the school.

De-Zhon, a neatly dressed, well-spoken boy who came back for a visit, conceded that he misses American Indian.

“I miss my class; I miss my teacher,” he said.

There are no televisions at American Indian -- no computers in the classrooms, either -- so there was no way for students to watch the inauguration. But Roberts wants to be clear: They wouldn’t have been allowed to watch it anyway.

“It’s not part of our curriculum,” she said.

Love it or hate it, it’s the American Indian way.

mitchell.landsberg @latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.