Clergy abuse case filled with silent bystanders

Long before Father Donald Patrick Roemer was charged with molesting a young boy, his behavior had been observed by churchgoers, fellow priests, school officials and police authorities. Yet none of them did anything.

- Share via

They stared at each other, the detective and the priest. Kelli McIlvain found interrogating him somewhat surreal. She had been raised Catholic and taught that a man in a black clerical shirt and white collar was nothing less than an emissary of God.

Father Donald Patrick Roemer was 5 feet 5, maybe 150 pounds. Hazel eyes. Blondish hair. A Ventura County Sheriff's Office report described him that night as "cooperative, seems stable," though McIlvain remembered how he repeatedly buried his head on the desk and wept.

To her surprise, his confession came easily. Yes, he said, he molested the 7-year-old boy.

McIlvain lit a cigarette. She hushed her voice, slowed her cadence to match his. Were there others, she asked. Yes, he said, according to court papers, and offered name after name.

"Where do I go from here?" he asked as midnight neared.

"Well," she said, "I'm going to have to arrest you."

What McIlvain uncovered in the weeks that followed seared the case into her memory, so much that she can recall its details more than three decades later, long after she retired: A number of people inside and outside the Catholic Church had been alerted to Roemer's misdeeds, or had strong suspicions of them, she learned.

They did nothing.

Experts call it the "bystander effect" — when people fail to help in potentially dire situations. Often they are more wary of falsely accusing someone than of their fears being confirmed. They question whether it's their responsibility to help, whether stepping in would do any good. If no one else is upset, they assume it's OK to walk away.

"We think our way out of situations we don't want to believe," said Pete Ditto, a UC Irvine professor who studies moral decision-making.

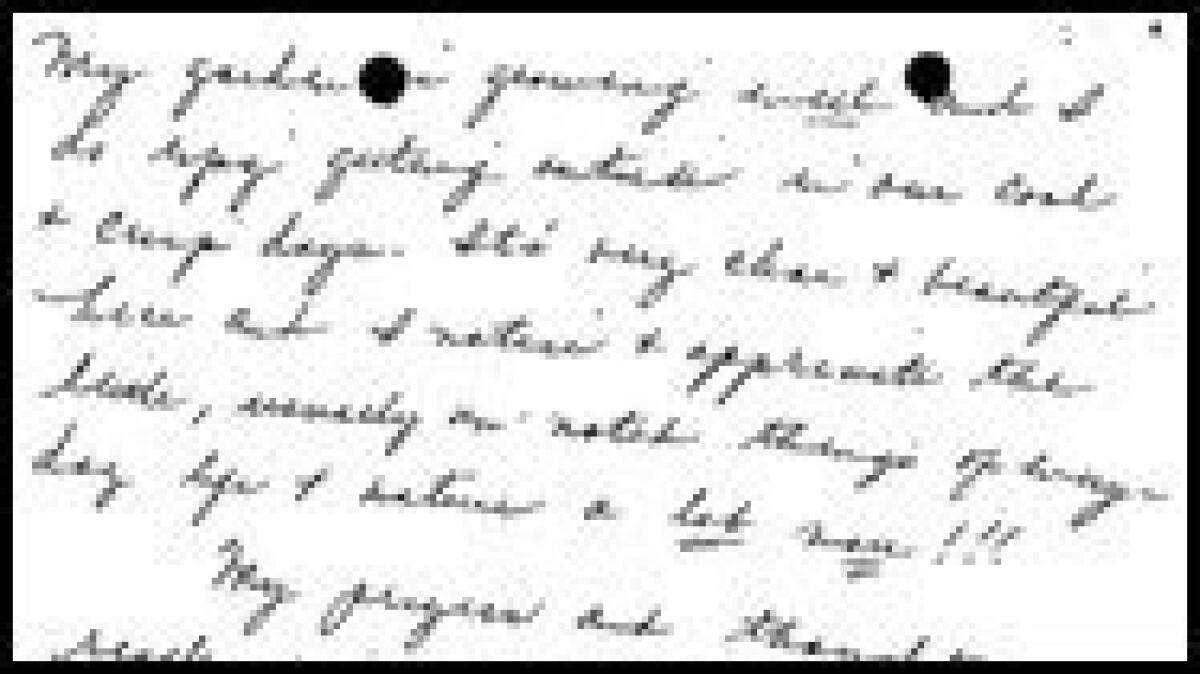

Retired Ventura County Det. Kelli McIlvain said that in her 21 years in law enforcement, she never handled an abuse case in which so many people could have interceded but didn't. (Jason Wise / For The Times)

According to the 12,000 pages of church records that the Archdiocese of Los Angeles made public this year, the phenomenon appears to have played a key role in allowing clergy sex abuse to fester in case after case.

Although Catholic leaders shoulder much of the blame for the abuse scandal, the culture of silence extended to teachers, secretaries and others in the church's bottom rungs. In certain cases, it took years for someone to tip off the archdiocese's top officials to suspected molesters, let alone authorities.

In the Los Angeles Archdiocese, school staffers sat on accusations against Father John Salazar for two years. A pair of youth group directors stayed silent for decades after Father Michael Terra confessed to what he described as a relationship with a 16-year-old girl. A priest who lived in the same rectory as Father Lynn Caffoe watched him take boys into his bedroom "hundreds of times." A housekeeper who tidied Father Michael Wempe's room noticed that more than once, a 10-year-old boy had slept over and soiled the bed.

We think our way out of situations we don't want to believe."— UC Irvine professor Pete Ditto

In Roemer's case, the list of people who suspected something was awry was particularly lengthy: churchgoers, fellow priests, school officials — even McIlvain's former boss.

Known in Ventura County as Father Pat, Roemer was well-aware of his demons. He had been sexually attracted to boys since he was young, he admitted to McIlvain, and had sought counseling for years from a fellow priest. That cleric, Roemer said, failed to provide him with much help.

"It's kind of like trying and trying and trying not to get involved in that, failing over and over again and not knowing what to do," he told McIlvain, according to a transcript of their interview. Roemer, now 69 and living in an Orange County apartment complex, according to public records, did not respond to requests for comment.

Since his ordination in 1970, Roemer hid behind a Mister Rogers veneer, parishioners said, doling out miniature Snickers and joking that his clerical collar repelled fleas. Any odd behavior was viewed through a certain prism, McIlvain learned, one that essentially inoculated him.

In the words of one parishioner who wrote to Roemer after his arrest: "We always see you as Jesus standing in the mists [sic] of our children."

An early opportunity to stop him came about 1976, when he was working in Santa Barbara. A few churchgoers said they marched into the archdiocese's religious education office to complain about how he and other priests behaved around children, court papers said.

Either no one passed those concerns up the hierarchy or no record was made of them. A top church official wrote years later that he had combed Roemer's file and could find "no indication of even a suspicion of wrongdoing" before his arrest.

Roemer moved to Thousand Oaks in 1978, when the city had about 77,000 residents and a reputation as one of California's safest. He oversaw youth services at St. Paschal Baylon, a parish of several thousand families.

Talk of child sex abuse was rare and the idea of a priest as a sexual predator unheard of. Instead of balking when Roemer ruffled their sons' hair, mothers thanked him for teaching the boys how to show affection. "He was the Pied Piper of the church," said Bill Sugars, whose two children attended St. Paschal.

I still remember one boy and the look he had on his face — the terror."— Shari Vener, whose son said he was stalked by Roemer

If parents thought it was strange that Roemer showed up at sporting events — even ones at public schools — they didn't speak up, McIlvain learned. He paced the sidelines with the coaches and sometimes crept up behind players and embraced them.

"I still remember one boy and the look he had on his face — the terror," said Shari Vener, who noticed Roemer at her son Ryan's flag football games. "I asked another mom, 'What's with him?' and she said, 'He just likes kids so much he can't keep his hands off them.' "

Later, Vener's own son had an encounter with Roemer at a sports camp that reduced him to tears.

No one really questioned why Roemer had few companions his age, McIlvain learned. His peers praised him as a sort of child whisperer; other parishes sent struggling children his way.

He took boys hiking at his family ranch. He treated them to movies. Over the years, they made him shirts to say thanks. One said, "Father Knows Best." Another, "Good Guys Wear Black."

In 1980, Roemer won a Parent Teacher Assn. award for his work with students.

"What a farce now," he told McIlvain.

On Jan. 26, 1981, Roemer stopped a 7-year-old boy who was on his way to religion class. "Do you want to see some pictures?" the priest asked, and the boy followed him to a teachers' lounge, court papers said. The boy didn't yet have the vocabulary to describe what happened next: The priest stroked the boy's "doofer" and then started shaking, the boy said.

Over dinner that night, the boy told his parents. "I felt like a tattletale," he said later. They called the sheriff's office and then-Deputy Bruce McDowell responded. "That little kid had not been coached," he recalled thinking, "and we needed to do something right away."

He notified McIlvain, who was working the night shift. As a mother, she understood the gravity of the accusations. She called the church, asked for Roemer and got her first hint that his crimes were no secret when one of his fellow priests replied: "Is this concerning a young boy?"

Later that night, Roemer confessed.

When news of his arrest broke, the vitriol it provoked was telling. In letters to the local News Chronicle, boys sneered at the charges. "Is it that wrong to show a little affection toward a child?" one asked. "Come on!"

Adults were more vicious. "What gives you the right to smear the name of a man of God and not the name of a 7-year-old, and don't give me that song and dance because the child is a minor and it is for his own protection," one woman huffed.

At the sheriff's station, deputies defended Roemer's character. Over and over, McIlvain reminded them: "He confessed to it."

Shari Vener sits in a park near her home in Murrieta. In the 1980s, her then 12-year-old son Ryan was preyed upon by Father Donald Patrick Roemer. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Vener, the mother who cringed at Roemer hugging football players, saw the headlines too. She turned to Ryan, then 12, and said, "I think we need to go to the police." Ryan balked. His mother insisted: "You need to go for those other kids, to validate them."

The boy met with McIlvain and told her that during the sports camp about seven months before Roemer's arrest, the priest had stalked him. At one point, Ryan said, Roemer told him, "You have such nice strong legs. Come up to my room after camp and I'll show you my yearbook." At another, Ryan said, the priest wrapped his arms around the boy and warned, "You can't get away from me."

In the ensuing months, said Ryan, now a married father of two, "I kept thinking he was going to come get me." He refused to go upstairs in his home. He felt uneasy around male teachers and coaches, and when his own father patted his back, Ryan sometimes shuddered.

Looking back, his mother wondered why she hadn't immediately called police, though it's common for victims and their families to hold their secrets close for years.

"I thought they'd say, 'That's what priests do, they love their flock,' " she said. "I feel guilty about it. Why didn't I do anything?"

The more McIlvain investigated, the more bystanders she found. In her 21 years in law enforcement, she said, she would never handle an abuse case in which so many people could have interceded but didn't.

McIlvain spoke to a special education teacher at a public elementary school where Roemer showed up every Monday at lunch to chat with students. About four months before his arrest, a mother confided in the teacher that Roemer had abused her son.

The teacher notified several supervisors, she said. By all indications, no one called police. Roemer's lunchtime visits continued, the teacher said, though he skipped the table where she and her pupils ate.

About a month before Roemer's arrest, another mother and son sat down with the priest's supervisor, Father Colm O'Ryan, McIlvain learned. A devout Catholic and religion teacher, the mother had joined St. Paschal's because she found Roemer engaging.

The mother and son told O'Ryan they had joined Roemer on a religious retreat in the San Bernardino Mountains area. With the boy's father asleep nearby, the 6-year-old asked Roemer to pray with him. The priest did, the boy said, and stuck his hand down the boy's pajama bottoms.

O'Ryan, the mother said, offered to get help for her son, who since the retreat had slashed the headboard of his bed with a knife and singed his blankets and pillows.

"I had nightmares about Father Roemer dying because he did sin," the boy said, according to court papers.

O'Ryan promised to discipline Roemer, the mother said, but instead sat on the accusations. He didn't get the boy counseling, either. The pastor, who recently retired from a parish in Beverly Hills, did not respond to requests for comment.

After arresting Roemer, McIlvain found a report someone had tossed on her desk. The mother and son who spoke to O'Ryan, the report said, had also alerted the sheriff's office. The mother was wary of pressing charges, but she expected deputies to do something.

Instead, Lt. Braden McKinley sought advice from a priest at the Catholic church where McKinley was a deacon. Then he talked to the mother. Because she said O'Ryan had promised to handle things, McKinley wrote in the report, "no further action is warranted by this department."

He never called Roemer. Or anyone at St. Paschal's.

McKinley said recently that he wasn't trying to cover up anything. Because the alleged abuse occurred in San Bernardino County, there was little he could do. McIlvain, however, remembered how woozy she felt reading his report, which ended with a definitive: "Case closed."

A few months later, in March 1981, Roemer pleaded no contest to molesting three boys. He spent nearly two years in a state mental hospital and was eventually defrocked. By 2004, the church had identified at least 13 others who said Roemer had abused them.

For McIlvain, one question still haunts her: Why didn't someone confront Roemer sooner?

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.