Times Investigation: LAPD misclassified nearly 1,200 violent crimes as minor offenses

- Share via

Once police had Nathan Hunter in handcuffs, they tended to his wife.

She was covered in blood. She told the officers Hunter flew into a rage that night in February 2013 because she hadn’t bought him a Valentine’s Day gift. He beat and choked her before stabbing her in the face with a screwdriver and throwing her down a flight of stairs at their apartment in South L.A., according to police and court records.

Hunter, 55, was convicted of felony spousal abuse and sentenced to six years in prison.

RELATED: Records show LAPD reclassified incidents

Under FBI rules followed by police departments across the country, the beating should have been counted as an aggravated assault because Hunter used a weapon and caused serious injuries.

That’s not what happened. The Los Angeles Police Department classified it as a simple assault — a minor offense not included in the city’s official tally of serious crimes.

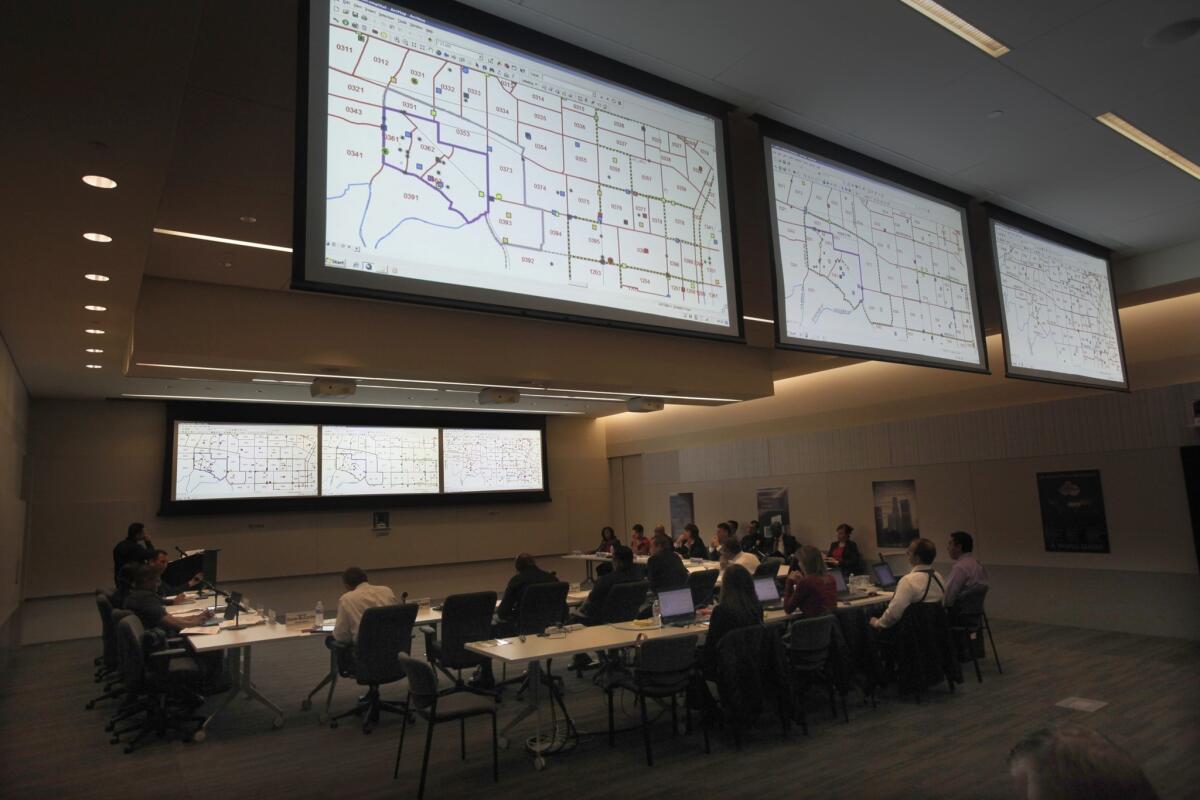

How the LAPD tracks and underreports crime statistics

It was no isolated case. The LAPD misclassified nearly 1,200 violent crimes during a one-year span ending in September 2013, including hundreds of stabbings, beatings and robberies, a Times investigation found.

The incidents were recorded as minor offenses and as a result did not appear in the LAPD’s published statistics on serious crime that officials and the public use to judge the department’s performance.

Nearly all the misclassified crimes were actually aggravated assaults. If those incidents had been recorded correctly, the total aggravated assaults for the 12-month period would have been almost 14% higher than the official figure, The Times found.

Whenever you reported a serious crime, they would find any way possible to make it a minor crime.

— Detective Tom Vettraino

The tally for violent crime overall would have been nearly 7% higher.

Numbers-based strategies have come to dominate policing in Los Angeles and other cities. However, flawed statistics leave police and the public with an incomplete picture of crime in the city. Unreliable figures can undermine efforts to map crime and deploy officers where they will make the most difference.

More than two dozen current and retired LAPD officers interviewed for this article gave differing explanations for why crimes are misclassified.

Some said it was inadvertent. Others said the problem stemmed from relentless, top-down pressure to meet crime reduction goals.

At the start of each year, top LAPD officials set statistical goals for driving down crime in the city. As part of that process, the department’s 21 divisions are given numerical targets for serious crimes each month.

Division captains, their command staff and other senior officials worry constantly about hitting their targets, officers said.

“Whenever you reported a serious crime, they would find any way possible to make it a minor crime,” Det. Tom Vettraino, who retired in 2012 after 31 years on the force, said of his supervisors. “We were spending all this time addressing what the crime should be called, instead of dealing with the crime itself. It’s ridiculous.”

In a written response to questions from The Times, LAPD officials said the department “does not in any way encourage manipulating crime reporting or falsifying data.”

Deputy Chief Rick Jacobs defended the crime-reduction targets, saying they are an important tool for tracking the department’s performance and holding division captains accountable. Captains are not judged solely on the numbers, but on the crime-fighting strategies they use, Jacobs said.

LAPD officials also say classification errors are inevitable in a department that records more than 100,000 serious offenses each year. They say the department has tightened its safeguards and improved its reporting accuracy.

“We recognize there is an error rate,” said Arif Alikhan, a senior policy advisor to Police Chief Charlie Beck. “It’s important to us to do what we can to reduce that error rate.”

The department “is relying on that data to determine where we are going to send cops … how we actually do things to prevent crime,” he added.

Alikhan, a former federal prosecutor and Homeland Security official, said the rate of misclassification has held steady or even declined over the years, so the public can trust figures showing that crime in L.A. has fallen in each of the last 11 years.

Beck declined to be interviewed. In a statement, he said classifying crimes is “a complex process that is subject to human error.”

If the misclassifications were mainly inadvertent, police would be expected to make a similar number of mistakes in each direction — reporting serious crimes as minor ones and vice versa, said Eli Silverman, professor emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

But The Times’ review found that when police miscoded crimes, the result nearly always was to turn a serious crime into a minor one.

Prompted by questions from Times reporters, the LAPD took steps this year to improve the accuracy of its statistics through training and “increased scrutiny of crime report classifications,” said Cmdr. Andrew Smith, the department’s chief spokesman.

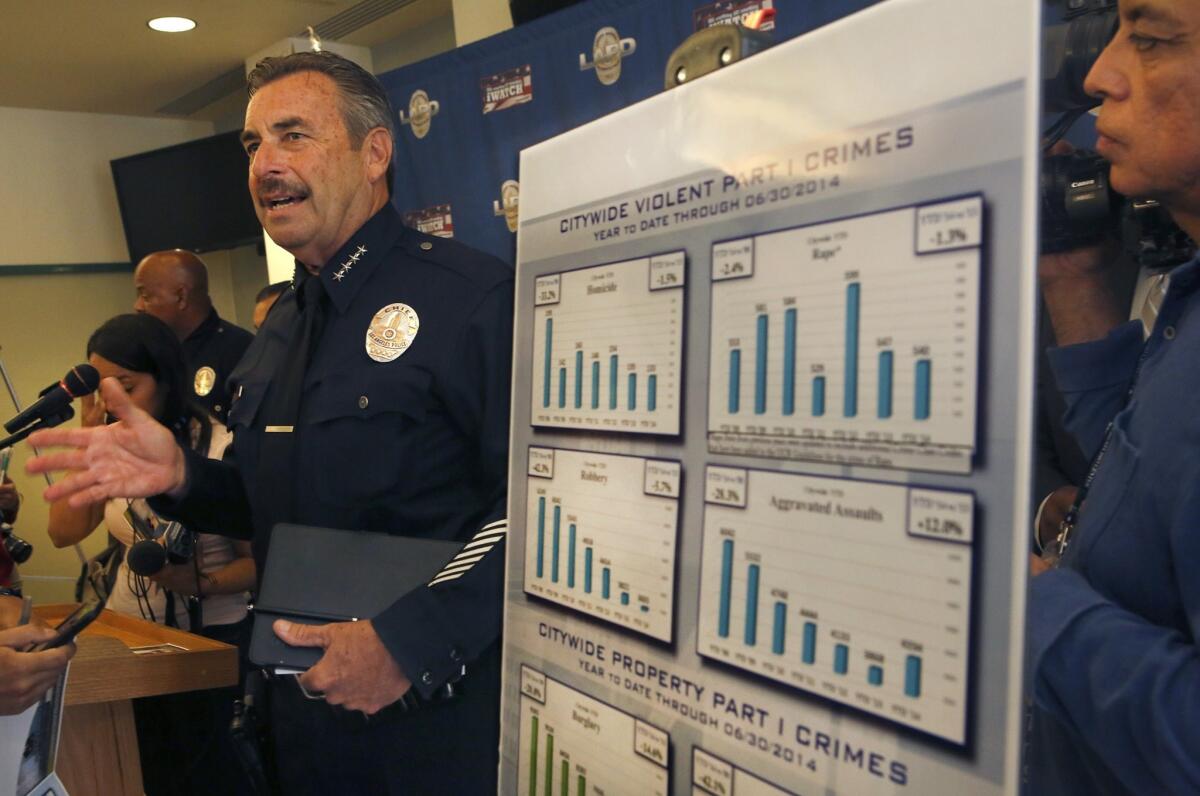

With stricter standards in place, the LAPD’s count of aggravated assaults rose 12% in the first half of 2014, compared with the year before. At a news conference last month to release the mid-year crime statistics, Mayor Eric Garcetti cited “more aggressive reporting” in explaining the increase.

That trend has continued. Through early August, the number of aggravated assaults was up 14.8% and violent crime overall was up 5.2% compared with the same period last year.

::

The LAPD collects data on all types of crimes, but published statistics focus on what the FBI defines as serious offenses: homicide, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, theft, motor vehicle theft and arson. The first four categories get the most attention.

The Times’ analysis of LAPD crime statistics was based on a year’s worth of data — from early October 2012 through September 2013 — obtained through public records requests. The information included brief summaries of officers’ reports for more than 94,000 crimes and showed how the incidents were classified.

Reporters searched the summaries for terms such as “stab” and “knife” to flag incidents that might meet the FBI criteria for serious offenses. They then read thousands of the summaries, which are typically two or three sentences long. They also reviewed court and police records for dozens of cases.

The Times compiled an initial list of nearly 2,000 misclassified crimes. Almost 1,400 were violent offenses; the rest were property crimes.

Reporters sought to confirm the findings by sharing data on a random sample of 400 incidents with five experts, including crime-reporting specialists at the Massachusetts, Michigan and Oregon state police. The sample was divided among the five experts for review.

Overall, they agreed with The Times in 90% of the cases that serious offenses had been recorded as minor crimes. Cases in which the experts disagreed with the newspaper’s assessment were removed from the tally of misclassified crimes. Incidents similar to those also were excluded.

LAPD officials questioned The Times’ analysis, saying the incident summaries might not accurately describe what happened. To address that concern, reporters gave the department a random sample of 200 assaults that appeared to have been misclassified.

The LAPD had its own auditors and an outside expert review the sample. Alikhan and Jacobs acknowledged that police had misclassified 89% of those cases and said the errors would be corrected.

Taking that into account, reporters ultimately determined that nearly 1,200 violent crimes had been improperly classified, of which almost 1,100 were aggravated assaults.

With accurate reporting, the city’s official count of violent crime for the one-year period would have been 18,046 instead of 16,849, the analysis found.

The misclassified cases included one in which a man suffered third-degree burns when his girlfriend poured boiling water on him as he slept, another in which a man stabbed his girlfriend with scissors and a third in which two men choked and beat a neighbor with a metal bar until he lost consciousness.

All three fit the criteria for aggravated assault but were recorded as minor offenses.

::

Compiling crime statistics is a multi-step process with the potential for errors or intentional distortion at various points.

When called to a crime scene, patrol officers interview the victim and witnesses and write a report that cites the state law they believe was violated.

A station supervisor is supposed to review the report and make sure the description of the offense is clear enough that a civilian clerk can later classify it correctly. The clerk enters a numerical code into the department’s crime database, designating it as a serious or minor offense under FBI rules. Detectives are supposed to provide a final check, ensuring the incident is classified correctly.

In the case of Nathan Hunter’s assault on his wife, his use of a weapon and the resulting injuries clearly fit the FBI’s definition of aggravated assault — an attack meant to inflict severe injury that usually involves the use of a weapon.

The officer who wrote Hunter’s arrest report described the incident as “spousal abuse.” A supervisor at the 77th Division approved the report without clarifying whether it was a simple or an aggravated assault. A clerk later typed in the code for simple assault.

LAPD officials declined to answer questions about the incident.

Breakdowns like the one in Hunter’s case have a ripple effect. CompStat, the department’s computerized tracking system, maps crime so officers can pinpoint trouble spots. But serious crimes that are misclassified don’t appear on those maps.

“I need those maps to be honest,” said a veteran officer, who requested anonymity because he feared retaliation for criticizing the department. “You’re taking tools away from me that I need to do my job.”

Department officials have publicly vouched for the accuracy of crime statistics.

“When I talk about these numbers, I’m confident,” Chief Beck said after announcing the city’s 2013 crime figures. “We make sure that they are accurate and that’s a huge concern for us. We don’t just put numbers out.”

Mayor Garcetti has said he wants the LAPD’s CompStat model replicated in other city departments, saying he believes it will increase efficiency and accountability.

Yet internal LAPD reviews have consistently found problems with the accuracy of crime statistics.

A 2009 audit identified fundamental flaws in the reporting process. “Auditors were unable to determine … who is responsible for determining appropriate crime code classifications,” the report concluded. “This lack of ensuring accountability may have attributed [sic] to the inconsistencies when determining the proper crime code classifications.”

That audit examined 383 simple assaults during a six-month period and found 1 in 10 should have been reported as aggravated assaults. Had the incidents been reported correctly, the city’s aggravated assault total would have been 32% higher than the official figure, The Times calculated.

More recently, a review of 105 assaults from July 2012 concluded that 3% of the simple assaults examined were actually aggravated assaults. If those incidents had been included, the department’s tally of aggravated assaults that month would have been about 10% higher.

In presenting the audits to the Police Commission in 2011, the LAPD’s top auditor, Jeffry Phillips, said the department was “doing relatively well” classifying crimes. Officials did not explain to the commissioners that, with accurate reporting, the city’s violent crime totals would have been significantly higher.

::

At that meeting, Beck did express concern over the potential for division commanders to “hide violent crime” by recording aggravated assaults as minor ones.

A disciplinary case dealing with that very problem had landed on Beck’s desk the year before.

John Elder, a veteran detective in the LAPD’s Southwest Division, had downgraded nearly 100 serious assaults to minor offenses, “resulting in a significant misrepresentation” of the division’s assault totals over a seven-month period in 2008, according to an internal investigation report.

Two clerks in the Southwest station told investigators Elder ordered them to record all cases of domestic violence as minor assaults, regardless of the facts — a strategy that further suppressed the division’s violent crime totals, according to the investigative report.

Elder denied the charges and said that any problems in the division’s statistics were inadvertent mistakes and the result of inadequate training.

His commanding officer, Capt. Steven Zipperman, found otherwise, concluding that Elder had deliberately attempted to “cook the books.”

“This is an integrity issue that erodes the basic foundation by which we are judged,” the report said.

The effects went beyond statistics: Assault victims “were not afforded the appropriate investigative urgency,” while suspects in some cases “were likely not given the immediate attention warranted,” according to the report.

Despite recommendations from Zipperman and others that Elder be fired, Beck concluded the detective had not acted deliberately. The chief reprimanded him and removed him as a supervisor.

Beck declined to discuss the case. Through an attorney, Elder also declined to comment. The LAPD recently paid $325,000 to settle a lawsuit in which Elder claimed the disciplinary case was part of a campaign of harassment, according to court and City Council records.

Several officers of various ranks said that manipulating crime figures is common, if typically less brazen than the conduct attributed to Elder.

A sergeant who is a supervisor in an LAPD station described a recent case of statistical sleight-of-hand.

After a maid had come to clean, items went missing from a house. Officers filed a report describing the incident as a theft — a serious crime under FBI guidelines. A lieutenant who oversees detectives ordered the crime, and all others like it in the future, to be classified as embezzlement, a minor offense that doesn’t register on the division’s crime totals, the sergeant said.

“Every little game like this has been tried over the years,” said the sergeant, who asked that his name not be published because he feared punishment for criticizing the department. “All of a sudden, we’re going to put somebody in jail for theft, but we’ll call it something else?”

Officers said it is widely believed that if their division repeatedly fails to meet targets for crime reduction, their chances of being promoted will be seriously harmed.

The department’s focus on numbers has “grown into a dog and pony show, a resource sucker, a cause for fear,” said Patrick Barron, who retired as a detective in 2012 after a 30-year career with the LAPD.

“Detectives should be worried about making sure their cases are thoroughly investigated and their victims and witnesses are treated with dignity,” he said. “They shouldn’t be worried about the statistics.”

For more coverage of accountability in law enforcement, follow Ben Poston and Joel Rubin on Twitter.

Times staff writers Ben Welsh and Doug Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.