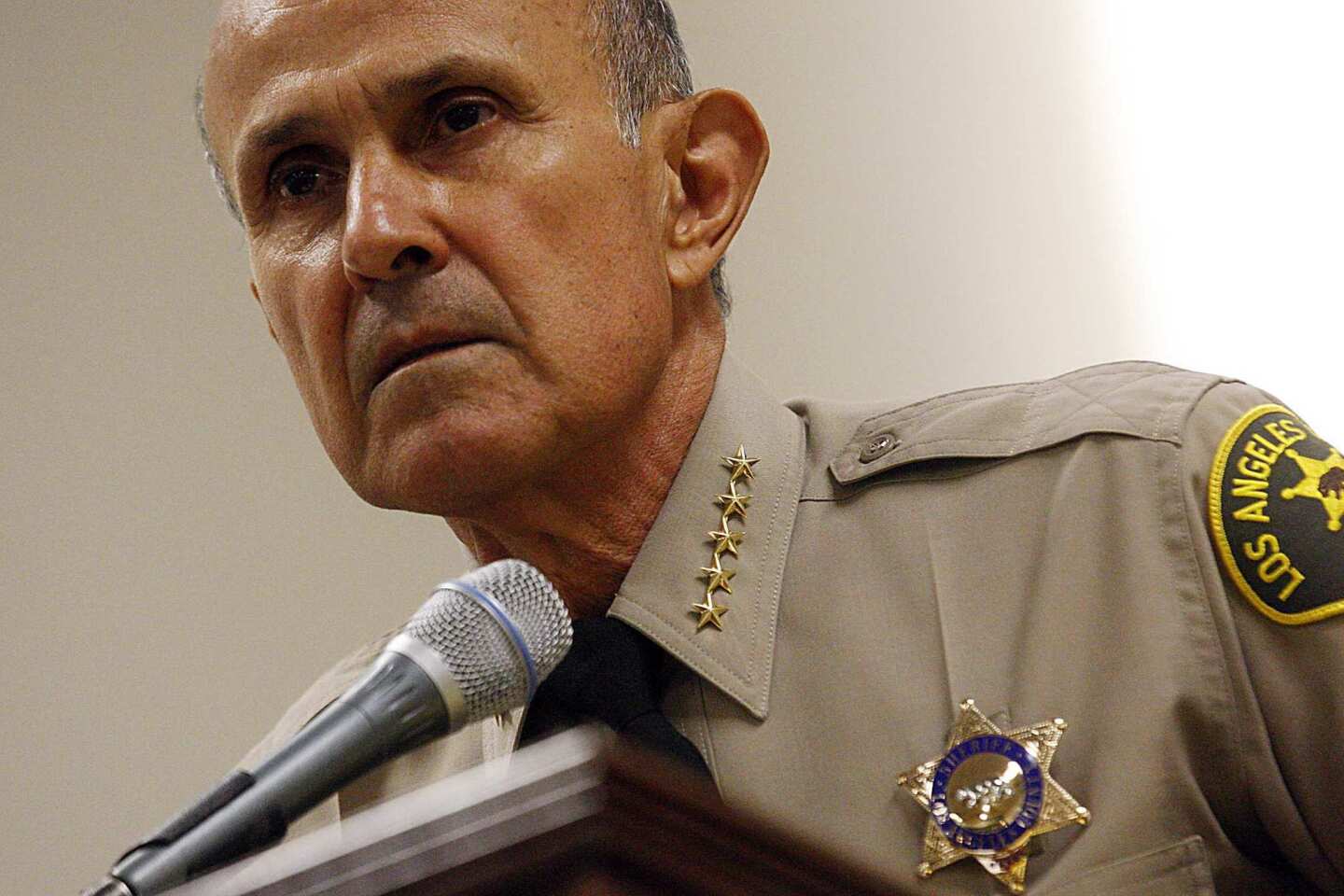

L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca agrees to long list of jail reforms

- Share via

Bowing to mounting pressure to fix the nation’s largest jail system, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca agreed Wednesday to sweeping reforms to improve the management and oversight of his agency amid allegations of deputy brutality against inmates.

One of the key recommendations accepted by Baca would create an independent inspector general’s office with the authority to scrutinize Baca’s agency. The move would significantly strengthen civilian monitoring by giving the outside body the power to conduct investigations inside the jails and elsewhere in the department.

Baca’s move comes several days after a blue-ribbon panel appointed by the county Board of Supervisors blamed him for problems of excessive force in the county’s lockups, which house about 19,000 inmates. The panel said Baca did not heed repeated warnings about brutality and other problems and did not pay attention to his jails.

FULL COVERAGE: Jails under scrutiny

Baca had resisted committing to the commission’s recommendations before they became public last week, but said Wednesday he planned to implement them all.

“I couldn’t have written them better myself....We will be a stronger and safer jail,” Baca said at a news conference on the third floor of Men’s Central Jail, the site of many of the most troubling allegations, including beatings and the formation of an aggressive gang-like deputy clique.

Baca spoke to reporters from inside the jail’s chapel, standing in front of a large cross while roughly 100 inmates clad in dark blue jail scrubs sat silently in the pews.

Flanked by about two dozen members of his command staff, the sheriff said he agreed with the commission’s suggestion that he hire an outside custody expert to run his jails, saying he has already started a nationwide search. Baca, however, said he had no immediate plans to discipline senior managers whom he had previously claimed kept him in the dark about the jails’ problems.

At the same time, Baca said Undersheriff Paul Tanaka is now under investigation over allegations in the commission’s report that he helped foster a culture of abuse in the jails. Baca raised doubts about those allegations, saying many of them were old and had been disputed.

Baca described the reforms as a historic shift for the Sheriff’s Department. Though the agency has for years been monitored by two civilian watchdogs, neither had the power to launch investigations, and the jail commission found that gaps in oversight allowed problems to go undetected.

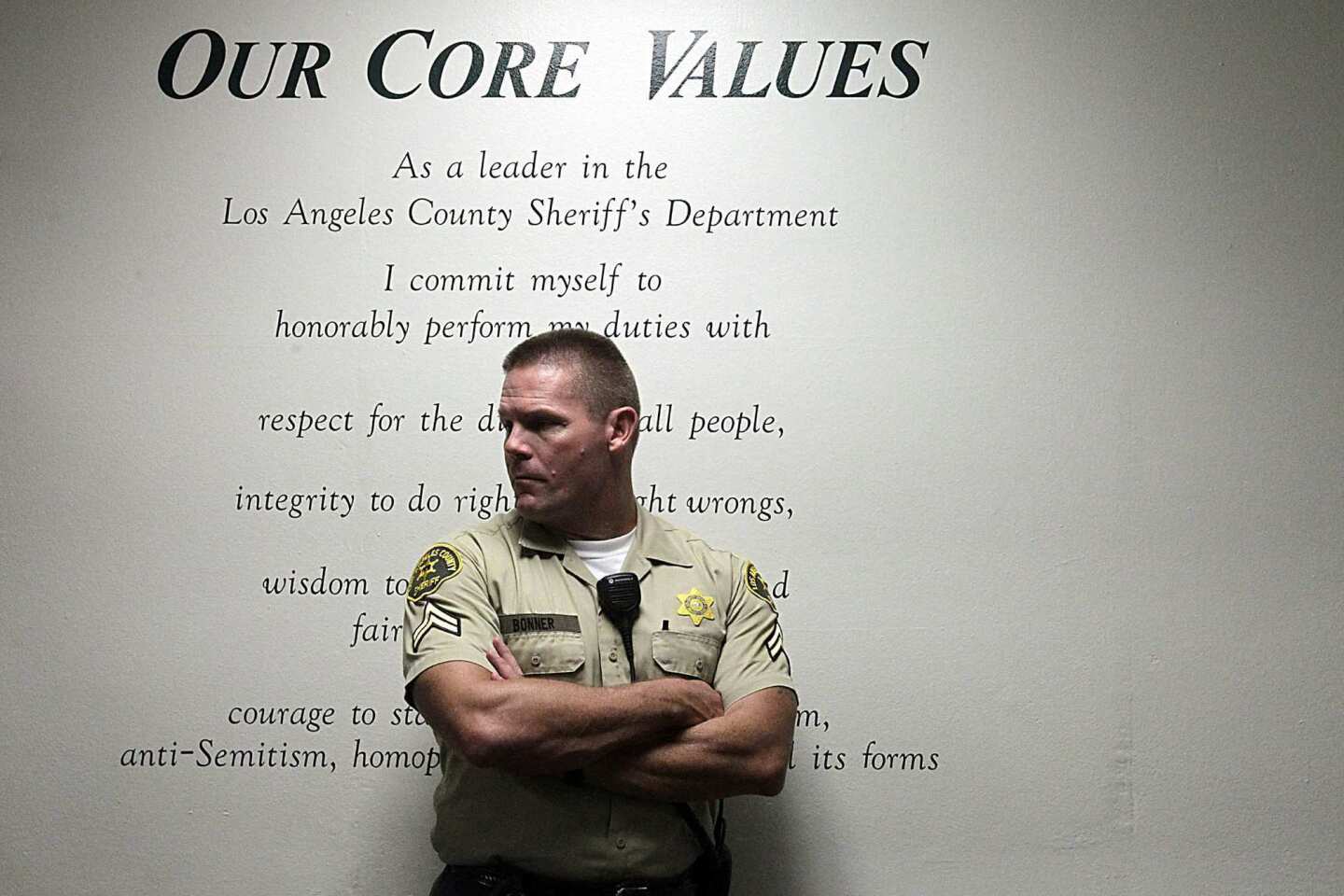

If Baca implements all 63 of the commission’s reforms, the changes would also have major implications for deputies working the jails.

The standard punishment for dishonesty would be dismissal rather than suspension. Deputies would no longer have their use of force investigated by the same sergeants who supervise them. And more supervisors would walk the jail floors to monitor deputies.

“I do have some deputies who have done some terrible things,” Baca said. “You can’t judge the whole by the few.”

The reforms include a major restructuring of the department’s workforce. Currently, all new recruits work the jails for several years before moving to patrol, creating a custody staff that’s young, inexperienced and often unhappy to be in the jails. By committing to the commission’s reforms, Baca agreed to create a separate custody division with a professional workforce of deputies who would spend their careers in the jails and grow experienced in how to manage inmates.

Baca said he has already gone a long way toward making reforms since the jail scandal erupted last year, when The Times revealed the FBI was secretly investigating deputy brutality and other misconduct in the jails. He said those changes had helped to dramatically reduce force. But he conceded that more needed to be done.

Peter Eliasberg, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said his organization welcomed Baca’s announcement but noted that the ACLU had complained for years about brutality in the jails. Miriam Krinsky, the executive director of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, said she was heartened that Baca had responded so positively.

“We’re very pleased,” she said. “We think it’s vitally important that there’s independent, comprehensive oversight and a vigilant eye to make sure commitments are carried out.”

The recommendations, made by a seven-member commission that included former judges and a police chief, were based on interviews with current and former Sheriff’s Department officials, jailhouse witnesses, testimony from experts, and internal department records. Its investigation painted a grim image of Baca’s jails over the years. Among the findings were that top supervisors joked about inmate abuse, encouraged deputies to push ethical boundaries and ignored alarming signs of problems with excessive force.

The commission called on Baca to become “personally engaged in oversight of the jails” and to “hold his high-level managers accountable for failing to address use-of-force problems.” Tanaka, Baca’s top aide whom the commission accused of discouraging discipline for misconduct, should have no responsibility for the department’s custody operations, the commission said.

At the news conference, Baca presented a new organizational chart that showed only administrative services reporting to Tanaka, who the sheriff said would continue to focus on the department’s budget.

Several inmates who were brought in to fill the pews at the news conference said they felt as though they were being used as props by the sheriff.

“It’s a dog and pony show,” said inmate Geoffrey Nielsen, 38. “We’re here to be pranced out.... People don’t deserve to get beat up for mouthing off.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.