Church Seeks Influence in Schools, Business, Science

- Share via

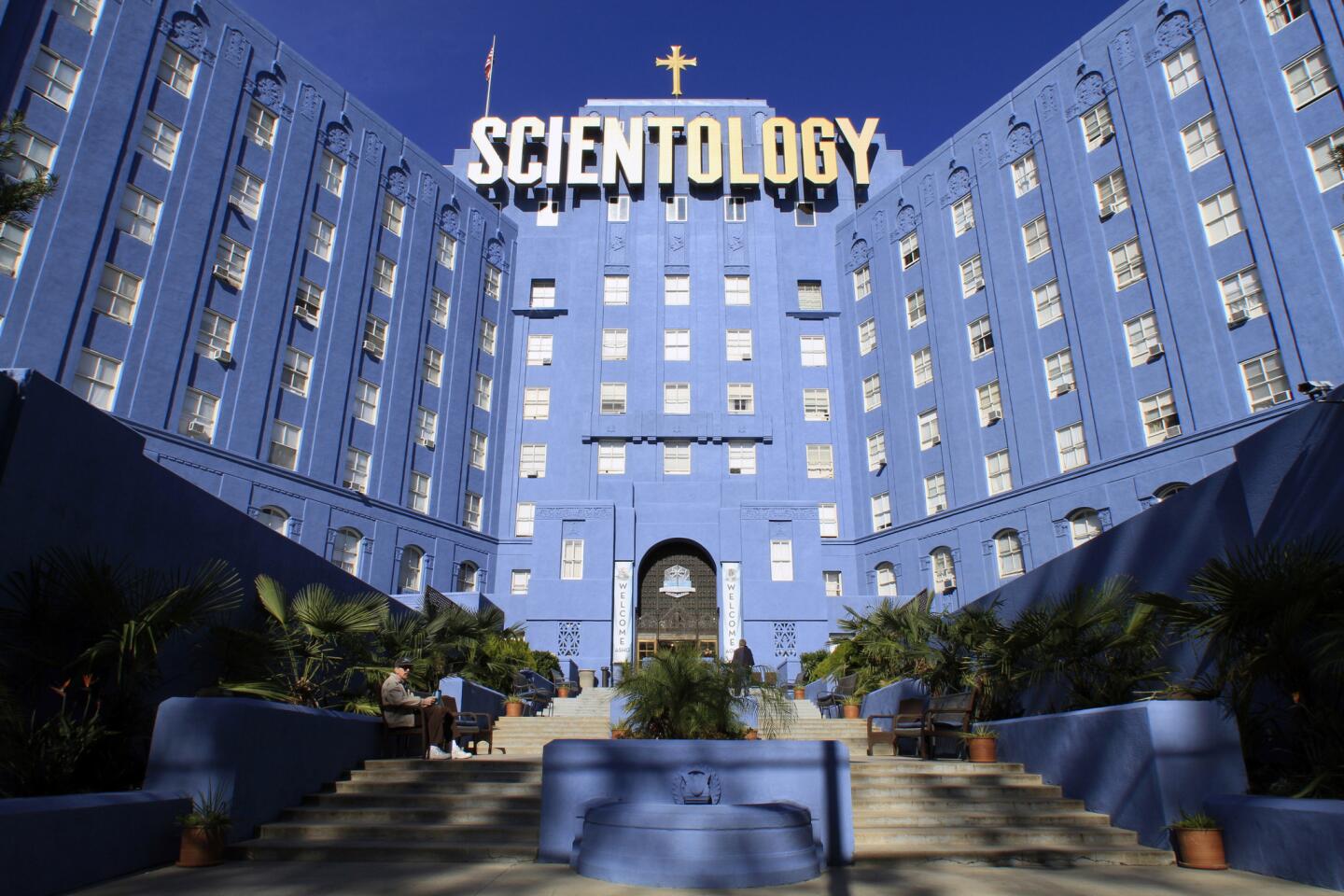

Emerging from years of internal strife and public scandal, the Scientology movement has embarked on a sweeping and sophisticated campaign to gain new influence in America.

The goal is to refurbish the tarnished image of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard and elevate him to the ranks of history’s great humanitarians and thinkers. By so doing, the church hopes to broaden the acceptability of Hubbard’s Scientology teachings and attract millions of new members.

The campaign relies on official church programs and a network of groups run by Scientology followers. Here is a sampler of their activities:

Scientologists are disseminating Hubbard’s writings in public and private school classrooms across the U.S., using groups that seldom publicize their Scientology connections.

In the business world, Scientologists have established highly successful private consulting firms to promote Hubbard as a management expert, with a goal of harvesting new, affluent members.

Scientologists are the driving force behind two organizations active in the scientific community. The organizations have been busy trying to sell government agencies a chemical detoxification treatment developed by Hubbard.

The Scientology movement’s ambitious quest to assimilate into the American mainstream comes less than a decade after the church seemed destined for collapse, testifying to its remarkable determination to survive and grow.

In 1980, 11 top church leaders--including Hubbard’s wife--were imprisoned for bugging and burglarizing government offices as part of a shadowy conspiracy to discredit the church’s perceived enemies.

Today, Scientology executives insist that the organization is law-abiding, that the offenders have been purged and that the church has now entered an era in which harmony has replaced hostility.

But as the movement attempts to broaden its reach, evidence is mounting that Hubbard’s devotees are engaging in practices that, while not unlawful, have begun to stir memories of its troubled past.

Scientology and the Schools

The Scientology movement has launched a concerted campaign to gain a foothold in the nation’s schools by distributing to children millions of copies of a booklet Hubbard wrote on basic moral values.

The program is designed to win recognition for Hubbard as an educator and moralist and, at the same time, introduce him to the nation’s youth.

The pocket-size booklet, entitled “The Way to Happiness,” is a compilation of widely agreed upon values that Hubbard put into writing in 1981. Its 96 pages include such admonitions as “take care of yourself,” “honor and help your parents,” “do not murder” and “be worthy of trust.”

The booklet notes in small print that it was written by Hubbard as “an individual and is not part of any religious doctrine.”

But Scientology publications have called the campaign “the largest dissemination project in Scientology history” and “the bridge between broad society and Scientology.”

Scientologists estimate that 3.5 million copies have been introduced into 4,500 elementary, junior high and senior high schools nationwide. Altogether, more than 28 million copies have been translated into at least 14 languages and distributed throughout the world.

The booklet is distributed by the Concerned Businessmen’s Assn. of America, an organization not officially connected to the church but run by Scientologists.

The Scientology connection is downplayed by the group. Its leader, Barbara Ayash of Marina del Rey, said she launched the association after five of her children became involved with drugs.

Her group runs a nationwide contest encouraging students to stay off drugs by following the precepts in Hubbard’s booklet. Participants in the “Set a Good Example” contest must come up with projects using the booklet as their guide. By focusing on the drug issue, the association has won the backing of school officials and political figures unaware of its links to Scientology.

In Louisiana, a junior high school distributed Hubbard’s booklet to students and then had them pledge in writing:

“I promise to do my best to learn, practice and use the 21 points of good moral conduct contained in ‘The Way to Happiness’ book to improve myself, set a good example for my friends, and to help my family, my community and my country.”

As an incentive to get campus administrators on board, the association awards $5,000 to the winning elementary, junior high and senior high schools.

At contest awards ceremonies, the winners and Hubbard’s book share the spotlight.

For example, during a ceremony at the Charleston, W.Va., civic center, then-Gov. Arch Moore and other dignitaries were each presented a leather-bound copy of “The Way To Happiness.”

Scientology critics contend that the contest is being used to enlist new church members, who, as the theory goes, may be so inspired by “The Way to Happiness” that they will reach for Hubbard’s other writings. They argue that the booklet’s distribution in public schools violates constitutional mandates separating church and state.

But Ayash of the businessmen’s association insists that her group has no motive other than to help children lead better lives. “The Way to Happiness,” she said, shows them the path in simple, direct language.

For the most part, school officials whose campuses have participated in the contest said they were unaware of Hubbard’s Scientology connection or that his followers were directing the contest. They said Scientology was not openly promoted and they did not regret taking part.

But one California public school system recently banned the contest after administrators conducted an investigation and learned that Hubbard was the author of Scientology’s doctrine.

For three years, students at El Capitan Middle School in Fresno participated in the nationwide contest. In Spring, 1989, the students won second place for organizing an anti-drug relay in which they passed each other a symbolic “torch”--Hubbard’s booklet.

Deluxe leather-bound copies were presented to mayors of the 15 cities along the relay route.

Last fall, the contest’s sponsors decided to accelerate their efforts in Fresno County, urging the entire 5,000-student Central Unified School District to participate, instead of just one school. But they ran up against Geoff Garratt, the district’s director of educational services and personnel.

Garratt said that, while he was aware of Scientology, he had never heard of Hubbard. He said he learned of the connection at the local library, where he went to investigate Hubbard’s background.

“The more I investigated,” Garratt said, “I found it (the businessmen’s association) represented a very small self-interest group: Scientology.” Among other things, he said, he discovered that the association had the same phone number and address as the local Dianetics center.

Garratt said he rejected the association’s plea to expand the contest, fearing that the booklet’s distribution in the public schools might violate constitutional prohibitions against mixing matters of church and state.

Garratt said the association refused to consider the possibility of holding the contest without Hubbard’s booklet. “They said flat out, ‘Without the book, there is no contest.’ ”

Scientologists also are attempting to install a Hubbard tutorial program in public schools, using a church-affiliated organization called Applied Scholastics.

Yellow posters advertising Applied Scholastics have appeared in storefront windows throughout Los Angeles. They promise better learning skills but make no mention of the church.

Applied Scholastics currently has plans to build a 1,000-acre campus, where the organization would train educators to teach Hubbard’s tutorial program. A recent Applied Scholastics mailer predicted that the training center will be a “model of real education for the world” and “create overwhelming public popularity” for Hubbard.

Developed for students of Scientology, the Hubbard program is built upon an elementary premise: learning difficulties arise when students read past words they do not understand.

“The misunderstood word in a subject produces a vast panorama of mental effects and is the prime factor involved in stupidity,” Hubbard wrote in 1967. “This is a sweepingly fantastic discovery in the field of education.”

The chief solution he propounds is simple: students must learn to use a dictionary when they encounter an unfamiliar or confusing word.

In recent years, Applied Scholastics has targeted predominantly minority schools, where many students tend to do poorly on standardized tests. Applied Scholastics considers these schools fertile ground because campus administrators are willing to try new approaches to improve scores.

The Compton Unified School District in 1987 and 1988 allowed the Hubbard program to be tested with 80 students at Centennial Senior High School. The program there was run by a substitute teacher named Frizell Clegg, a Scientologist who was an Applied Scholastics consultant.

Clegg, who refused to be interviewed, was suspended from his teaching duties in 1988 after he reportedly gave discourses on Scientology in a history class. He no longer teaches at the school.

In applying for district financing, Clegg said the educational program was “developed by American writer and educator L. Ron Hubbard.” Excluding any reference to Hubbard’s Scientology connection, he persuaded the board to provide $5,000 to tutor 30 sophomores with low reading scores and to conduct a parent workshop.

After the program grew to 50 students, Applied Scholastics submitted a proposal increasing the number of students to 125 and the cost to $27,000.

District officials killed the program, believing that Applied Scholastics was seeking to expand too quickly. Officials were also displeased that the group, without district approval, was using its involvement with Centennial to market the program elsewhere, according to Acting Supt. Elisa Sanchez.

In promotional literature, Applied Scholastics made claims of remarkable success at Centennial High. While some parents said the program helped their children, Sanchez said the claims made by Applied Scholastics were unsubstantiated.

Converting the Business World

Scientology is using a network of private consulting firms to gain a foothold in the U.S. business community.

The firms promise businessmen higher earnings but appear to be mainly interested in recruiting new members for the church.

Although these profit-making firms operate independently of each other, they sell the same product: Scientology founder Hubbard’s methods for running a profitable enterprise. The Church of Scientology has for years employed these same methods--heavy marketing, high productivity and rigid rules of employee conduct--to amass hundreds of millions of dollars for itself.

Critics contend that the consulting firms are concealing their Scientology links so they can attract to the church prosperous people who might otherwise be put off by Scientology’s controversial reputation.

The strategy appears to have proven effective.

A Scientology publication in 1987 reported that the consultant network earned a combined $1.6 million a month selling Hubbard’s management methods to a variety of professionals, many of whom have reported improved incomes. It also said that 50 to 75 businessmen were recruited monthly into the church, where each week they spent a total of $250,000 on Scientology courses.

Two of the movement’s firms have been ranked by Inc. magazine as among the fastest growing private businesses in America.

The consulting firms use seminars and mailers to attract health professionals, salesmen, office supply dealers, marketing specialists and others.

Those who have dealt with the firms describe the process this way:

Businessmen are drawn into Scientology after they have gained confidence in Hubbard’s non-religious management methods. They are often told that, to achieve true business success, they should get their personal lives in order. From there, the church takes over, encouraging them to purchase spiritual enhancement courses and begin a process called “auditing.”

During auditing, a person confesses his innermost thoughts while his responses are monitored on a lie detector-type device known as the E-meter. Auditing must be purchased in 12 1/2-hour chunks, costing between $3,000 and $11,000 each, depending on where it is bought.

Spearheading all this is an arm of the church called World Institute of Scientology Enterprises, or WISE.

In recent months, WISE has been encouraging Scientologists nationwide to become consultants within their respective professions. The appeal is simple: make money while disseminating your religion.

In the process, WISE profits, too. It trains and licenses the firms to sell Hubbard’s copyrighted “management and administrative technology.” WISE charges roughly $12,000 for its basic no-frills training course. For consulting services, it charges $1,875 a day.

On top of this, the consulting firms that sell Hubbard’s business methods must pay WISE 13% of their annual gross income.

At the heart of Hubbard’s business system is a concept he called “management by statistics,” which he said guarantees optimum office efficiency. Scientology critics maintain, however, that it creates an oppressive and regimented workplace environment.

An employee is judged solely upon his productivity, which is charted on a graph each week. Sagging productivity could bring a rebuke from the boss. Or it could lead to an employee’s firing.

The management techniques promoted by the consulting firms are identical to those used by the church, except that all Scientology references have been deleted from the materials. The consultants even employ the most basic instrument used by the church to recruit new members off the street--a 200-question personality test that purports to let people know if they have ruinous personality flaws.

The consultants encourage businessmen and their employees to purchase Scientology courses to remedy personality problems uncovered by the test.

One of the most successful consulting firms licensed by WISE is Sterling Management Systems, which targets dentists and other health care professionals. For the past two years, Inc. magazine has ranked it among America’s fastest-growing privately held businesses.

Sterling, based in Glendale, claims to be the “largest health care management consulting group in the U.S.”

A company spokesman said the firm charges clients $10,000 for its complete line of Hubbard courses and 30 hours of private consultation. The spokesman said Sterling has helped dentists increase their income an average of $10,000 a month.

He insisted that the company has “no connection” to the church, but added: “If people are interested in Scientology, we will make it available to them.”

Sterling publishes a tabloid called “Today’s Professional, the Journal of Successful Practice Management.” Mailed free to 300,000 health care professionals nationwide, it is filled with “management” articles by Hubbard that are actually excerpts from Scientology’s governing doctrines.

The company also holds nationwide seminars that, according to its promotional literature, have been drawing 2,000 people a month.

Sterling Management was founded in 1983 by Scientologist Gregory K. Hughes, at the time a prosperous dentist in Vacaville, Calif. Hughes holds seminars across the country, offering himself as evidence that Hubbard’s methods work.

In promotional publications for Sterling, Hughes has said that his annual income soared from $257,000 in 1979 to more than $1 million in 1985. In one month alone, he has claimed to have seen 350 new patients.

Sterling’s paper, Today’s Professional, has boasted that “the techniques that produced amazing results when applied to Greg’s practice are being applied all over the U.S.”

But neither the paper’s readers nor those who attend Hughes’ seminars are told that his dental office, which employed the high-volume Hubbard techniques that he imparts to others, has been accused by former patients of dental negligence and malpractice.

Hughes currently is under investigation by the California Board of Dental Examiners. The board already has turned over some of its findings to the state attorney general’s office, which will determine whether action should be taken against Hughes’ dental license.

To date, there are more than 15 lawsuits pending against Hughes and his dental associates, alleging either negligence or malpractice. He has denied the allegations.

Attorney E. Bradley Nelson is representing most of those who have sued Hughes.

“It is my opinion,” he said, “that the overall quality of care took second place to the profit motive. . . . I’ve never seen anything approaching this volume of complaints against one dentist in such a short period of time.”

In mid-1985, Hughes closed his office without warning to devote full time to Sterling. He left behind a reputation so tarnished that he was unable to sell his million-dollar-a-year practice, according to dentists in the area.

“He actually had to walk away,” said Roger Abrew, co-chairman of the peer review committee of local dental society.

He also left behind patients with worse problems than they had before they were treated by Hughes’ office, according to Abrew and other dentists, who have since been treating them. The dentists said that, based on their examinations, Hughes’ office performed both substandard and unnecessary work.

“I think its kind of ironic to see a guy who did such a botched job of dentistry teaching others,” said dentist David C. Aronson, summing up the sentiments of most of his colleagues in the small Northern California community.

Hughes, who continues to conduct his “Winning With Dentistry” seminars, refused to be interviewed for this story. But Frederick Bradley, an attorney defending him in the lawsuits, suggested that the Vacaville dentists may simply resent his client’s success because their patients had deserted them for Hughes.

Another firm once licensed by Scientology’s WISE organization to sell Hubbard’s management techniques was Singer Consultants. Before it merged with another management company, Singer was ranked as one of the nation’s fastest growing private businesses.

The company focused its training on America’s chiropractors. It brought hundreds of new members into the church and triggered a nationwide controversy among chiropractors over its links to Scientology. In fact, a chiropractic newspaper devoted almost an entire issue to letters praising and condemning Singer Consultants, which was located in Clearwater, Fla., where Scientology is a major presence.

“We felt that there were young doctors who didn’t know they were being solicited to do something above and beyond the practice of their profession,” said Dynamic Chiropractic editor Donald M. Peterson, explaining why his Huntington Beach-based newspaper entered the controversy.

Singer Consultants was headed by Scientologist David Singer, an accomplished speaker and chiropractor who held nationwide seminars to pitch Hubbard’s business methods.

Two years ago, the company was absorbed into another management firm owned by Scientologists.

Although Singer refused to be interviewed by The Times, he told Dynamic Chiropractic: “Hubbard was a prolific writer and wrote on a multitude of subjects. We do not, have not and will not make part of our program the teaching of any religion.”

Scientology and Science

Hubbard was so proud of a detoxification treatment he developed--and so hungry for plaudits--that he openly talked with his closest aides about winning a Nobel Prize.

Although the man is gone, Scientologists are keeping the dream alive. They have embarked upon a controversial plan to win recognition for Hubbard and his treatment program in scientific and medical circles.

The treatment purports to purge drugs and toxins from a person’s system through a rigorous regimen of exercise, saunas and vitamins--a combination intended to dislodge the poisons from fatty tissues and sweat them out.

Physicians affiliated with the regimen have touted it as a major breakthrough, and a number of patients who have undergone the treatment say their health improved. But some health authorities dismiss Hubbard’s program as a medical fraud that preys upon public fear of toxins.

In the Church of Scientology, the treatment is called the “purification rundown.” Church members are told it is a religious program that, for about $2,000, will purify the body and spirit. In the secular arena, however, Scientologists are promoting it exclusively as a medical treatment with no spiritual underpinnings. In that context, it is simply called the “Hubbard Method.”

The treatment is being aggressively pushed in the non-Scientology world by two organizations that sometimes work alone and sometimes in tandem. They have no formal church ties but both are controlled by church members.

Seeking customers and credibility, the two groups have targeted government and private workers nationwide who are exposed to hazardous substances in their jobs. They have pressed public agencies to endorse the method, lobbied unions to recommend it and written articles in trade journals that seem to be little more than advertisements for the treatment.

One of these groups is the Los Angeles-based Foundation for Advancements in Science and Education. The nonprofit foundation has forged links with scientists across the country to gain legitimacy for itself and, thus, for Hubbard’s detox method.

Among its key functionaries is a toxicologist for the Environmental Protection Agency, whose advocacy of the treatment has raised conflict-of-interest questions.

Building credentials and allies, the foundation has channeled tens of thousands of dollars in grants to educators and researchers studying toxicological hazards, most of whom were unaware of the organization’s ties to the Scientology movement.

In 1986, for example, the foundation gave $10,000 to the Los Angeles County Health Department for a study of potentially harmful radon gas. County officials say they were not apprised of the organization’s links with the Scientology movement.

Bill Franks was instrumental in creating the foundation in 1981 when he served as the Church of Scientology’s executive director, a post from which he was later ousted in a power struggle. Franks described the foundation in an interview as a Scientology “front group.”

“The concept,” he said, “was to get some scientific recognition” for Hubbard’s treatment without overtly linking it to the church.

Buttressing Franks’ account, the foundation’s original incorporation papers state that its purpose was to “research the efficacy of and promote the use of the works of L. Ron Hubbard in the solving of social problems; and to scientifically research and provide public information and education concerning the efficacy of other programs.”

The document was later amended, however, to remove Hubbard’s name, obscuring the foundation’s ties to the Scientology movement and its founder in official records.

Hubbard’s name, however, continues to appear regularly in the foundation’s slick newsletter. In the latest edition, for instance, three different articles advocate the “Hubbard method” as an effective therapy for chemical and drug detoxification.

A fourth article did not mention Hubbard by name, but reported favorably on Narconon, his drug and alcohol rehabilitation program, which is run by Scientologists.

The other organization in the outreach effort is HealthMed Clinic, which administers Hubbard’s treatment from offices in Los Angeles and Sacramento and is run by Scientologists.

An independent medical consultant in Maryland who reviewed the program for the city of Shreveport, La., dismissed Hubbard’s treatment as “quackery.”

The foundation and HealthMed have attempted to create an impression that they are linked only by a shared concern over toxic hazards. In reality, however, they operate symbiotically.

The foundation, for its part, tries to scientifically validate the Hubbard method through studies and articles by individuals who either are Scientologists or hold foundation positions. HealthMed then uses the foundation’s credibility, writings and connections to get customers for the treatment.

According to state corporate records, the foundation also holds stock in HealthMed. Moreover, the foundation’s vice president, Scientologist Jack Dirmann, has served as HealthMed’s administrator.

In 1986, four doctors with the California Department of Health Services accused HealthMed of making “false medical claims” and of “taking advantage of the fears of workers and the public and about toxic chemicals and their potential health effects, including cancer.” The doctors also criticized the foundation for supporting “scientifically questionable” research.

The state physicians, who evaluate potential toxic hazards in the workplace, leveled the accusations in a letter that triggered an investigation by the state Board of Medical Quality Assurance. That probe was concluded last year without a finding of whether the detox treatment works. Investigators said they were stymied by HealthMed’s refusal to provide patient records and by a lack of complaints from those who had undergone the regimen.

The four physicians who prompted the investigation said they decided to study the Hubbard treatment after receiving calls from union representatives, public agencies and individual workers throughout the state who had been solicited by the clinics. Among them were the California Highway Patrol, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Pacific Gas & Electric Co. and the Los Angeles County Fire and Sheriff’s departments.

“It was the accumulation of these calls that led us to say, ‘Hey, this is going on all over the state. Let’s look into it,’ ” recalled Gideon Letz, one of the doctors.

The foundation and HealthMed have worked particularly hard to tap one large pool of potential clients: firefighters. The Hubbard method has been pitched to them as a cure for exposure to a carcinogen sometimes encountered during fires. Known as PCBs, the now-banned chemical compound was once widely used to insulate transformers.

City officials in Shreveport, La., said they paid HealthMed $80,000--and were ready to spend a lot more--until they hired a consultant, who denounced the treatments as unnecessary and worthless.

What happened in Shreveport is a case study of how the foundation and HealthMed have worked together to draw customers through methods that critics contend are exploitative.

In April, 1987, dozens of Shreveport firemen were exposed to PCBs when they responded to an early morning transformer explosion at the Louisiana State University Medical Center. In the aftermath, some began to complain of headaches, dizziness, skin rashes, memory loss and other symptoms that they attributed to the exposure.

Blood and tissue tests by the university medical center showed no abnormal levels of PCBs in their systems. But the firemen wondered if the university was trying to protect itself from liability because the explosion had occured there.

Searching for alternatives, one of the firemen came across an article in Fire Engineering magazine. Headlined “Chemical Exposure in Firefighting: The Enemy Within,” it was written by Gerald T. Lionelli, “senior research associate for the Foundation for Advancements in Science and Education.”

Lionelli discussed the frightening consequences of chemical exposure and then got to the point. He said the foundation had found an effective detoxification technique developed by “the late American researcher L. Ron Hubbard” and delivered by HealthMed Clinic.

The article did not mention another of Hubbard’s notable developments--Scientology.

The firemen contacted HealthMed, and, before long, were sold on the program. They went next to Howard Foggin, then the city’s medical claims officer, and gave him HealthMed literature and a Washington, D.C., phone number the clinic had provided them. It was for the office of EPA toxicologist William Marcus.

Marcus, a non-Scientologist, is a senior adviser to the foundation. But it is his authoritative position with the EPA’s office of drinking water that helps impress potential HealthMed clients.

When Shreveport officials called Marcus, he vouched for HealthMed. The EPA had spoken, or so the city’s claims manager thought back then.

“All he told me was, it seemed I had no alternative but to send those people to Los Angeles” for HealthMed’s treatment, Foggin said, adding: “I felt I had to get moving on it fast.”

In an interview with The Times, Marcus acknowledged that he recommended HealthMed, but he denied any conflict of interest.

“They called me and I talked to them,” Marcus said. “I told them that basically there was no other game in town. . . . I think L. Ron Hubbard is a bona fide genius.”

Marcus said he receives only travel-related expenses for the foundation work.

His boss, Michael Cook, said he is satisfied that Marcus did not act improperly. He said that Marcus has insisted “he made it clear that he was not speaking as an EPA employee. Certainly that is what we would hope and expect he (would) do.”

In all, HealthMed brought about 20 Shreveport firefighters to Los Angeles to treat what the clinic described as high levels of PCBs in their blood and fatty tissues. For the most part, the firemen returned home saying that they felt better.

Although city officials had learned of Hubbard’s Scientology connection, they were unconcerned.

Then, as HealthMed’s bills mounted, two private insurance carriers for Shreveport suggested that city officials hire an independent analyst to review the treatment before doling out more money. The city agreed and commissioned a study by National Medical Advisory Service Inc., of Bethesda, Md.

The report, prepared by Dr. Ronald E. Gots, was an indictment of HealthMed’s professionalism and ethics. The bottom line:

“The treatment in California preyed upon the fears of concerned workers, but served no rational medical function. . . . Moreover, the program itself, developed not by physicians or scientists, but by the founder of the Church of Scientology, has no recognized value in the established medical and scientific community. It is quackery.”

Gots’ 1987 report ended the city’s involvement with HealthMed.

“I think we were misled,” lamented city finance director Jim Keyes. “Somebody should have laid everything out on the table.”

Neither HealthMed nor the foundation would return phone calls from The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.