Costly Strategy Continues to Turn Out Bestsellers

- Share via

Call it one of the most remarkable success stories in modern publishing history.

Since late 1985, at least 20 books by Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard have become bestsellers.

In March of 1988, nearly four decades after its initial publication, Hubbard’s “Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health” was No. 1 on virtually every best-seller list in the country--including the New York Times.

Ten hardcover science fiction novels Hubbard completed before his death four years ago also became bestsellers, four of them simultaneously on some lists.

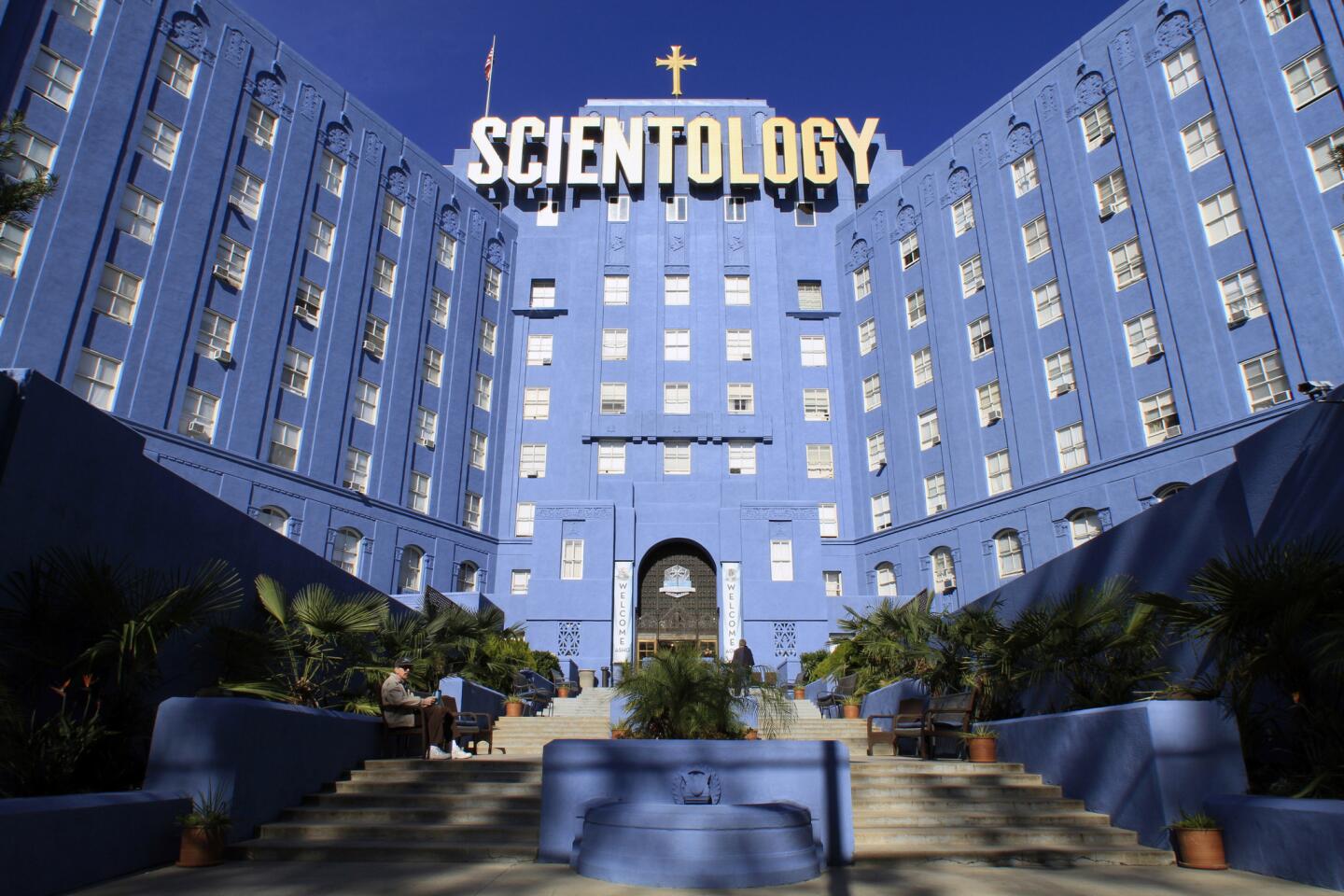

The selling of L. Ron Hubbard was envisioned, planned and executed by members of the Church of Scientology, who say that worldwide sales of Hubbard’s books have topped 93 million. The sales have been fueled by a radio and TV advertising blitz virtually unprecedented in book circles, and has put on the map a Los Angeles publishing firm that eight years ago did not even exist.

In some cases, sales of Hubbard’s books apparently got an extra boost from Scientology followers and employees of the publishing firm. Showing up at major book outlets like B. Dalton and Waldenbooks, they purchased armloads of Hubbard’s works, according to former employees.

As a writer, Hubbard was extremely prolific. He wrote short stories. He wrote books. He wrote screenplays. And, for more than 30 years, he wrote thousands of directives and scores of personal improvement courses that form the doctrine of Scientology.

The promotion of Hubbard’s books is part of a costly and calculated campaign by the movement to gain respect, influence and, ultimately, new members. In the process, Hubbard’s followers hope to refurbish his controversial image and position him as one of the world’s great humanitarians and thinkers.

Hubbard’s writings have become a means by which to spread his name in a society that often equates celebrity with credibility. It is not with whimsy that the church often calls its spiritual father “New York Times best-selling author L. Ron Hubbard.”

The church once summed up the strategy in a letter recruiting Scientologists for Hubbard’s public relations team, an operation that thrives despite his death. Sign up now, the letter urged, and “make Ron the most acclaimed and widely known author of all time.”

But apparently Hubbard’s followers have not trusted sales of his books entirely to the fickle winds of the marketplace.

Sheldon McArthur, former manager of B. Dalton Booksellers on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, said, “Whenever the sales seem to slacken and a (Hubbard) book goes off the bestsellers list, give it a week and we’ll get these people coming in buying 50 to 100 to 200 copies at a crack--cash only.”

After Hubbard’s first novel, a Western adventure called “Buckskin Brigades,” was re-released in 1987, the book “just sat there,” recalled McArthur, whose store was across from a Scientology center.

“Then, in one week, it was gone,” he said. “We started getting calls asking, ‘You got ‘Buckskin Brigades?’ ” I said, ‘Sure, we got them.’ ‘You got a hundred of them?’ ‘Sure,’ I said, ‘here’s a case.’ ”

Gary Hamel, B. Dalton’s former manager at Santa Monica Place, had similar experiences. He said that “10 people would come in at a time and buy quantities of them and they would pay cash.”

Hamel also speculated that some copies of a Hubbard science fiction novel were sold more than once.

He said that while he was working at the B. Dalton in Hollywood, some books shipped by Hubbard’s publishing house arrived with B. Dalton price stickers already on them. He said this indicated to him that the books had been purchased at one of the chain’s outlets, then returned to the publishing house and shipped out for resale before anyone thought to remove the stickers.

“We would order more books and . . . they’d come back with our sticker as if they were bought by the publisher,” Hamel said.

Hubbard’s U.S. publisher is Bridge Publications Inc., founded and controlled by Scientologists--something that Bridge does not publicize. Company officials refused to be interviewed about book sales or any facet of the firm’s operations.

But former employees alleged in interviews with The Times that Bridge encouraged and, at times, bankrolled the book-buying scheme.

Mike Gonzales, a non-church member who worked in accounts receivable, said one supervisor gave him hundreds of dollars for weekend forays into bookstores.

In one month alone, he said, he bought and returned to Bridge 43 books in Hubbard’s “Mission Earth” science fiction series. And, according to Gonzales, he was not alone.

“We had 15 to 20 people going all over L.A.,” he said.

During a shopping spree at B. Dalton in the Glendale Galleria, Gonzales said, he bumped into three Bridge co-workers.

“There we were, four people in line buying ‘Buckskin Brigades,’ and (the clerk) blurted out, ‘You know why they do that? To get on the bestsellers list!’ ”

Corinda Carford, who was Bridge’s sales manager for the East Coast, said she was instructed by two superiors to go to bookstores and buy Hubbard’s books if sales were sluggish.

“They would tell me to go and count the books and . . . if it looks like they’re not selling, go and buy some books,” Carford recalled. She said she was troubled by the request and bought only four copies of one Hubbard paperback.

Carford said Bridge executives also asked her in late 1988 and again in early 1989 to obtain the names of bookstores whose sales are the basis for the New York Times bestseller list.

“It happened more than once,” she said. “ . . . My orders for the week were to find the New York Times’ reporting stores anywhere in the East so they could send people into the stores to buy (Hubbard’s) books.”

Carford said she questioned several bookstore operators but they refused to cooperate.

“That is confidential information,” she said.

Carford said she left Bridge after a pay dispute and now works for another publishing firm.

Another former Bridge employee, salesman Tom Fudge, said a supervisor once handed him a list of booksellers purportedly monitored by the New York Times. He said he was instructed to promise each one that Hubbard’s books would “sell well” if they stocked more copies.

“I was told that they (Bridge) had Scientologists who would go out to specific stores and buy copies of the books,” Fudge said.

An attorney who represents Bridge and Scientology denied that the publishing firm possessed a list of bookstores the New York Times uses to determine bestsellers.

“The list does not exist,” insisted Boston lawyer Earle Cooley, who characterized the former employees as “disgruntled” and “antagonistic” toward Bridge and Scientology.

Adam Clymer, a New York Times executive, said the newspaper has examined the sales patterns of Hubbard’s books. In a two-year span, Hubbard logged 14 consecutive books on the New York Times list.

Clymer said that, while the books have been sold in sufficient numbers to justify their bestseller status, “we don’t know to whom they were sold.”

He said the newspaper uncovered no instances in which vast quantities of books were being sold to single individuals.

Science fiction and self-improvement books have always been big sellers in America, and Hubbard’s works have long had a strong following.

But Bridge learned quickly that to make him a best-selling author in the 1980s, it had to aggressively market his writings, especially within the bookselling industry.

As part of its campaign Bridge has purchased full-page ads on the cover of Publishers Weekly, an important trade magazine.

For a time, the firm was enticing book distributors to place large orders by offering them free television sets and VCRs.

Marcia Dursi, director of book operations for ARA Services in Maryland, which distributes paperbacks to supermarkets and airports, said she was offered a TV for the employee lunchroom.

“I don’t have to be bribed,” Dursi said she responded.

Former Bridge consultant Robert Erdmann said that, while other publishers offer incentives, he stopped the practice at Bridge because “it could be perceived as influence peddling.”

Erdmann, a non-Scientologist, was an industry veteran hired by Bridge to help make inroads in the competitive publishing world.

Because the Scientologists at Bridge “did what we told them to do,” Erdmann said, “Dianetics” is no longer “the passion fruit of the Pacific that people in the Midwest are afraid to eat.”

When it was first published in 1950, “Dianetics” rode bestseller lists for several months before sales dwindled. But it has remained the bedrock--”Book One”--of Hubbard’s Scientology movement.

In “Dianetics,” Hubbard said that memories of painful physical and emotional experiences accumulate in a specific region of the mind, causing illness and mental problems. Hubbard said that, once these experiences have been purged through cathartic procedures he developed, a person can achieve superior health and intelligence.

So revered is the book that Hubbard scrapped the conventional calendar and renumbered the years beginning with the date of its publication. To Scientologists, 1990 is “40 AD” (After Dianetics).

From the outset, the Scientology movement has made the book the centerpiece of its campaign to generate broad interest in Hubbard’s writings.

In the last few years, millions of dollars have been spent on “Dianetics” advertising to reach a targeted audience of young professionals who want to improve their lives and careers.

The ads have appeared on television, radio, billboards and bus stops.

“Dianetics” has been a sponsor of the California Angels and Los Angeles Rams games on radio. Race cars in world-class competitions such as the Indianapolis 500 have sported “Dianetics” decals. In New York City recently, 160 billboards promoting Hubbard were purchased in subway stations.

Next month, in what may be the Scientology movement’s biggest promotion yet for the book, Dianetics will be a sponsor of Turner Broadcasting System’s 1990 Goodwill Games, an Olympics-style event bringing together 2,500 athletes from more than 50 countries for two weeks in Seattle.

Among other things, there will be Dianetics commercials during the internationally televised competition and Dianetics signboards at sporting venues. Goodwill Games spokesman Bob Dickinson said that Dianetics and 12 other sponsors--including Pepsi, Sony and Anheuser-Busch--have paid “lots and lots of money” for the exposure, but he would not provide a specific figure.

“It is safe to say it is in excess of several million dollars,” Dickinson said.

Word of the sponsorship has triggered more than 100 complaints from disaffected Scientologists and critics of the church to TBS, the Atlanta-based cable network owned by media entrepreneur Ted Turner. Most have accused the network of providing a global forum for the Church of Scientology.

But Dickinson said that Dianetics, not Scientology, is the event’s sponsor and that “we really don’t make any value judgment in terms of the product of the sponsors. They have a right to advertise.” He added that Dianetics for years has been buying air time on TBS.

Although Dianetics advertisements never mention Scientology, the book’s promotion is a key component of the church’s efforts to win new converts. Scientology literature calls the strategy the “Dianetics route.” The idea is to attract readers to Dianetics seminars and then enroll them in Scientology courses.

Given the success of the Dianetics campaign, Bridge now seems confident that the public will clamor for Hubbard’s Scientology writings.

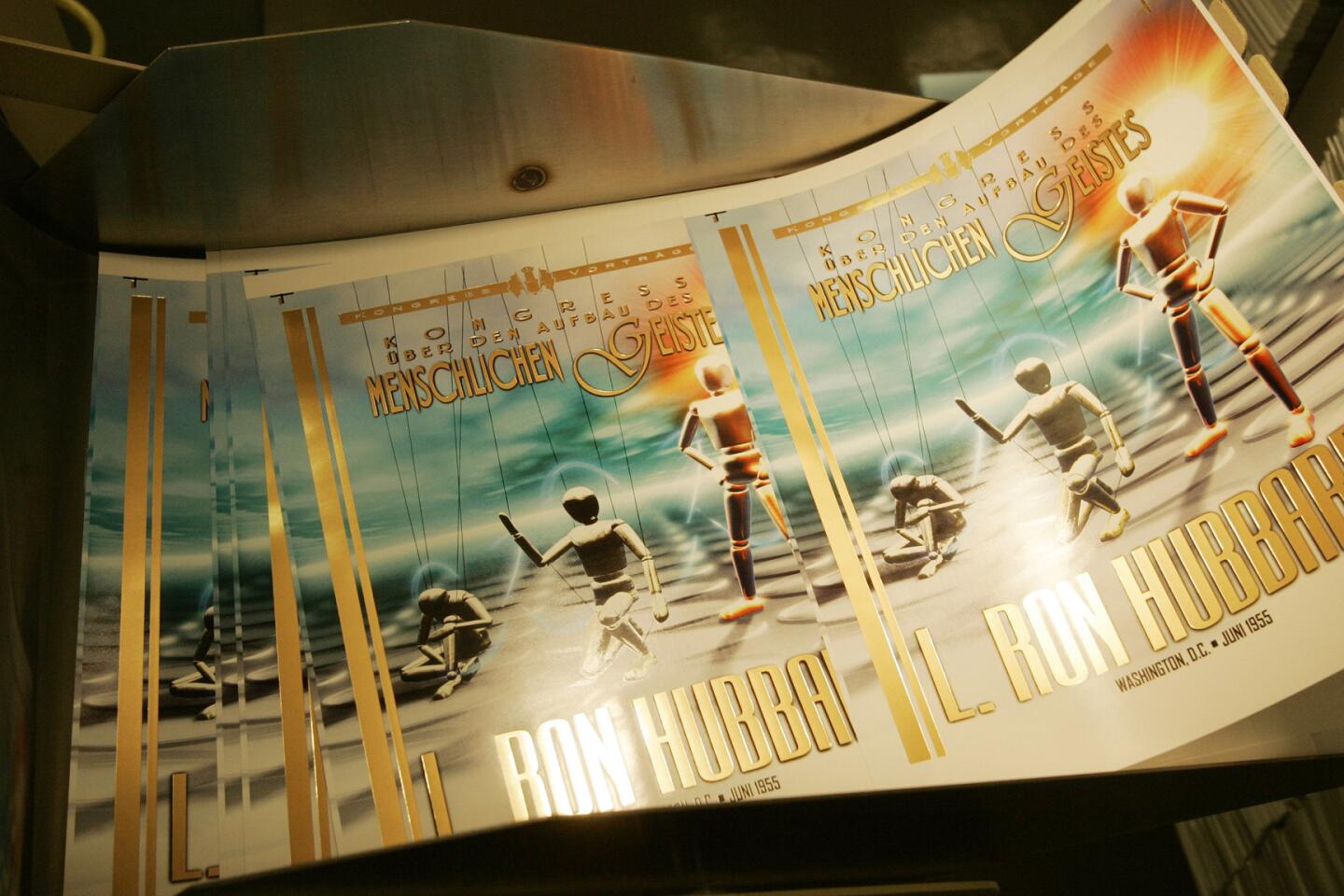

Hubbard books that for decades had no audience outside Scientology are scheduled to be mass-marketed into the next century, complete with costly promotional campaigns as big as that for “Dianetics.”

One of them, Hubbard’s 1955 “Fundamentals of Thought,” has “Scientology” splashed across its cover, the first test of whether Hubbard’s image has been so greatly improved that the public is finally ready to accept his religion.

Even long-forgotten science fiction that Hubbard wrote back in the 1930s will be dusted off, dressed in eye-grabbing covers and pushed as though it were written today.

In recent months, billboards have appeared along Los Angeles freeways and such well-traveled thoroughfares as Sunset Boulevard.

With the sea as a backdrop, they show a smiling Hubbard of earlier years, the wind tousling his red hair. Below his robust image is the phrase: “22 national bestsellers and more to come . . . “

The selling of the late L. Ron Hubbard has only begun.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.