Nearly 1 in 4 students at this L.A. high school migrated from Central America — many without their parents

- Share via

Gaspar Marcos stepped off the 720 bus into early-morning darkness in MacArthur Park after the end of an eight-hour shift of scrubbing dishes in a Westwood restaurant.

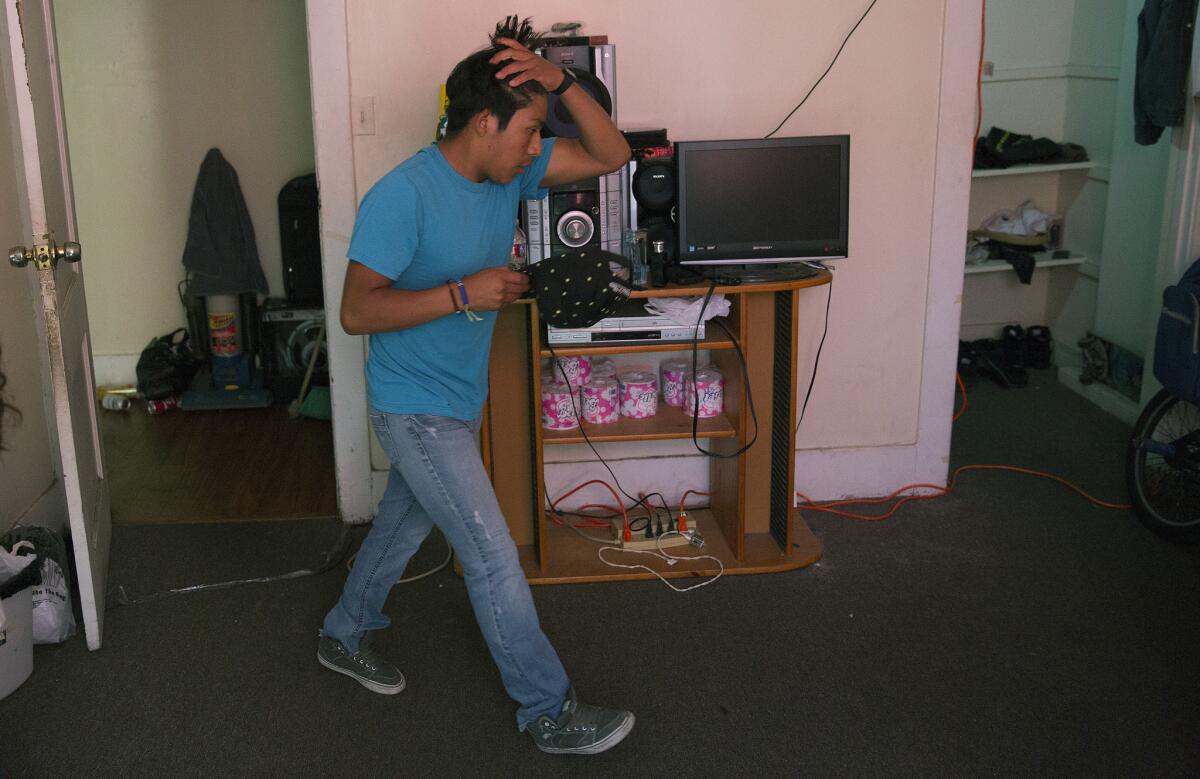

He walked toward his apartment, past laundromats fortified with iron bars and scrawled with graffiti, shuttered stores that sold knockoffs and a cook staffing a taco cart in eerie desolation. Around 3 a.m., he collapsed into a twin bed in a room he rents from a family.

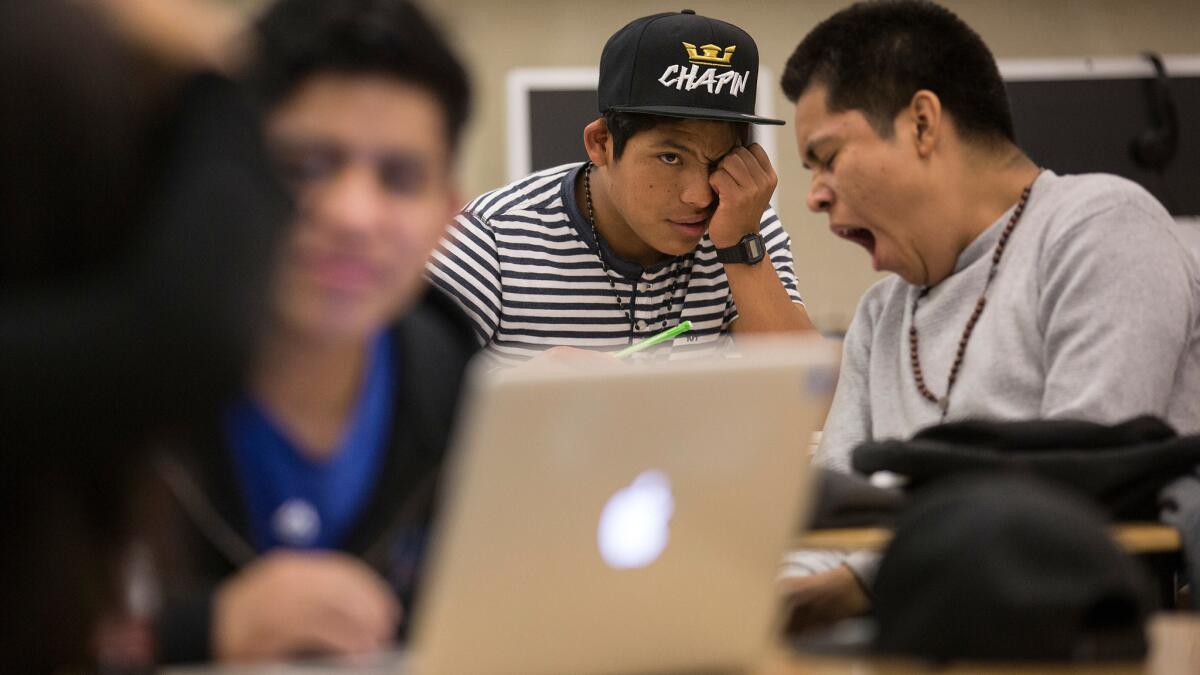

Five hours later, he slid into his desk at Belmont High School, just before the bell rang. The 18-year-old sophomore rubbed his eyes and fixed his gaze on an algebra equation.

Minutes ticked by, and others straggled into the class, nine in all. Like Marcos, most had worked a full shift the night before — sewing clothes, cooking in restaurants, painting homes.

Most were immigrants from Central America, part of several waves of more than 100,000 who arrived as children in the U.S. in the past five years without parents, often after perilous journeys.

Gaspar Marcos is an unaccompanied minor in Los Angeles. This is his story.

Many ended up in classrooms throughout the country. In Los Angeles’ Belmont High, nearly 1 in 4 of the school’s estimated 1,000 students came from Central America — many of them as unaccompanied minors.

They crossed the border to reunite with mothers and fathers or to find refuge from unprecedented gang violence at home. Some dare to dream they will find success in America, not just the means to survive.

Belmont Principal Kristen McGregor said it has forced the school to reimagine its role in its students’ lives.

“Our students, a lot of them have to work. A lot of them have to send money home or pay for rent,” she said. “This is going to take a rethinking of education in general. Sure, they get into school, but what’s next? How do we support them?”

She first noticed a surge of students from Central America in the spring 2013. Some of the Guatemalan students spoke only indigenous languages, such as Quiche and Mam. She bought a Quiche dictionary. For the hungriest, McGregor turned a bookcase into a food pantry stuffed with canned peas, Sloppy Joe sauce and dried fruit.

When some students ended up homeless, she found places for them to stay.

“They come here to have a better life, but that’s not always the case,” McGregor said.

::

Marcos grew up in an indigenous village in Huehuetenango, a poor community where most residents speak Chuj. When he was 5, his mother and father fell ill. There was no doctor in town, and they died.

Orphaned, Marcos was taken in by a neighbor. She kicked him out when he was 12.

“You’re a man now,” she said. “You have to find your own way.”

Marcos shined shoes to scrape together a living. He earned enough money to put himself through the better private school in his village, where he learned to read and write in Spanish. A year later, work dried up, and the teenager set his gaze north. He called up a half-brother who lived in L.A.

Marcos had never even been to Guatemala City. He wore a T-shirt and pants for the long trip. He forgot to take a backpack.

Like most children who make the journey to the U.S. without a parent or guardian, a smuggler — often referred to as a coyote — is paid to guide them along the trip.

Marcos spent three days lost and without water in the Sonoran Desert. He didn’t eat for a week. At one point, he fainted. The smuggler abandoned him after he fell behind.

He made it to Falfurrias, Texas, where Marcos said he was kidnapped by two men who wanted him to pay $3,000 to let him go.

They spoke only English, and Marcos spoke some Spanish. They used a translation app on a cellphone, he said. Marcos said he was able to negotiate the price down to $1,000. His relative wired the money and bought him a bus ticket to Los Angeles. But immigration officials caught him in Arizona.

He was 13 at the time, so they gave him a notice to appear in immigration court, before releasing him to a half-brother he’d never met. A few months later, the brothers had a falling out, and Marcos struck out on his own.

He got a job paying about $5 an hour to sew clothes in a factory in downtown L.A.

Later, he’d land a job at a restaurant making $10.50 an hour and he’d pay $600 a month in rent as well as a few hundred dollars in groceries. Every month, he peeled off $300 to pay off the $10,000 smuggling debt that brought him to the U.S.

“What can I do?” he said in Spanish. “It’s just the life I was given to lead.”

::

His formal learning cut short in Guatemala, Marcos knew that education was “the most important thing.”

“If you don’t have education, nobody will respect you,” he said. “If you don’t educate yourself, you don’t have employment. I want to be a good person and have an education … have a good, stable job. I want to have a home, the sort of home I never had.”

McGregor said some of the immigrant children who came to L.A. showed up at Belmont in the Westlake neighborhood almost immediately. Others enrolled a few years later, having first gone to work.

Because of this, many students, like Marcos, are older than other students at their grade level.

“They start here in the ninth grade, regardless of how old they are,” McGregor said. “Some finish at 19 or 20 years old.”

Many of these children have ended up at Belmont High because it had a reputation for welcoming them.

At Belmont, teachers contend with the trauma many of these children suffered in their countries of origin or along the treacherous journey north. Some of the students struggle against resentment and abandonment issues while getting to know a mother, father or family member who left them behind. Some run away.

Some of algebra teacher Marvin Centeno’s students studied until only the third or fourth grade in their home country.

At the same time they are trying to learn and working, many of the students also have to navigate a complex immigration system that will decide whether they get to stay in the U.S., said Federico Bustamante, who manages a transitional shelter for unaccompanied migrant children called Casa Libre.

Bustamante helped Marcos retain a pro-bono attorney through Kids in Need of Defense, an advocacy organization that works to find representation for these children in immigration court.

Marcos was allowed to stay at Casa Libre until he turned 18. A condition of staying there was attending Belmont High, something Marcos thought he couldn’t do because he wasn’t in the country legally. At school, he declined to take food from the makeshift pantry, believing other students needed it more. But he devours any advice from McGregor about improving his English.

Marcos has at least one advantage over some immigrant students: He was able to receive a special immigrant juvenile visa, usually given to children who were found to have been abused, neglected or abandoned by one or both parents. That makes him eligible for legal residency, for which he’s in the process of applying.

But he still struggles with balancing school and work. Many of the immigrant students attend school every day, McGregor said. But for some, work and other complications become an obstacle to education.

Worried about earning enough money, Marcos rarely turns down extra work shifts. Sometimes he oversleeps and misses morning classes. Other days, he doesn’t show up at all. A’s and Bs started sinking into Cs. McGregor often turns to pleading with students like him to show up.

“If you have to pay off a coyote who brought you up here, at what point does school play a role?” she said.

During his second-period biology class, Marcos thumbed through two textbooks — one in English, one in Spanish — with a laptop within reach.

“What are some of the plants that live in this biome?” he read out loud to himself, pulling on the top of his hair as he searched for the answer.

When a student sitting next to him asked Marcos a question in Chuj, he answered in Spanish, thinking it disrespectful to leave other classmates out of the conversation.

The last week of school, Marcos was in and out. McGregor pulled him aside and again urged him to come to school. On the very last day, his desk sat empty during first-period algebra, and then again during his biology class.

When third-period history started, he slid into his desk.

Twitter: @thecindycarcamo

Para leer esta historia en inglés haga clic aquí

ALSO

How Mexican immigrants ended ‘separate but equal’ in California

Her toddler suddenly paralyzed, mother tries to solve a vexing medical mystery

L.A. Unified takes a harder look at its charter schools. Critics blame politics

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.