He got into Georgetown as a bogus tennis recruit. Was he in on college admissions scam?

- Share via

To hear his lawyers tell it, Adam Semprevivo has worked hard to earn high marks his whole life — both before and after his father paid $400,000 to ensure an unsuspecting Adam was admitted to Georgetown University as a bogus tennis recruit.

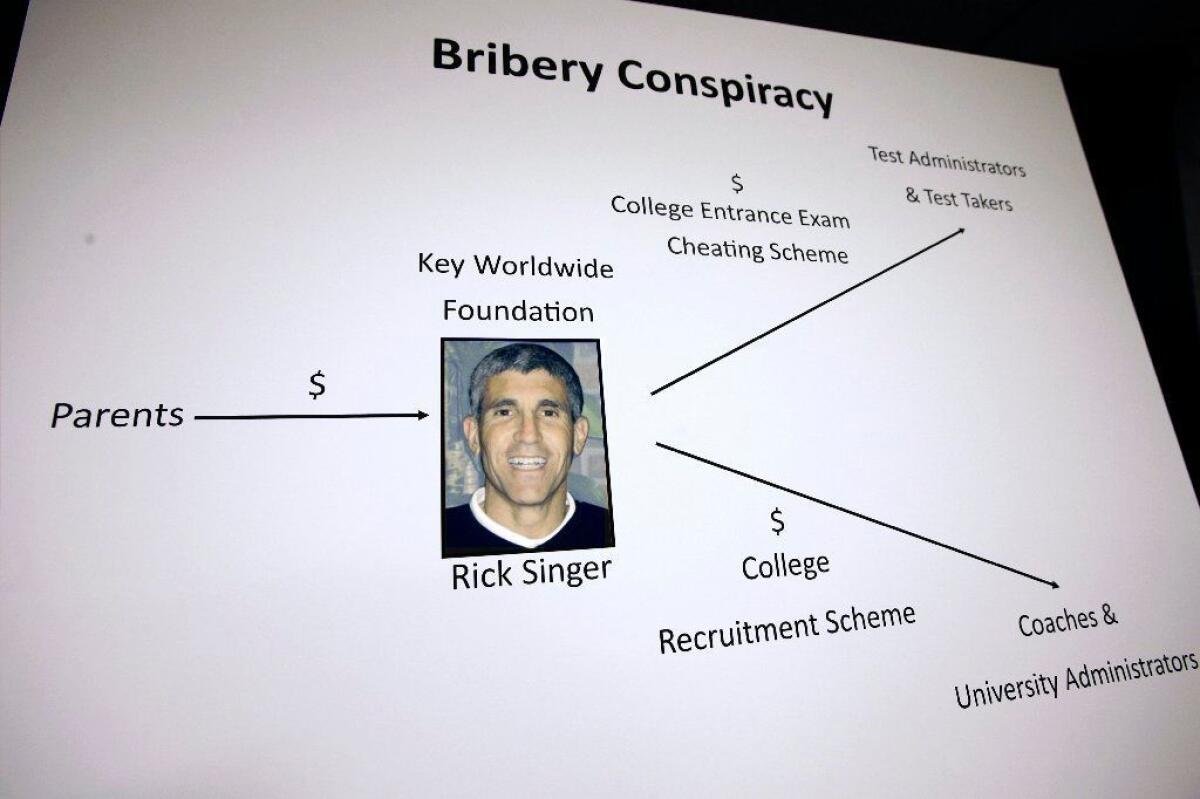

He was misled, his lawyers wrote in a lawsuit filed Wednesday against Georgetown, by his father and a college admissions consultant who has since admitted to paying millions of dollars to crooked coaches in a cash-for-admission conspiracy that breached some of the country’s most selective universities.

But in the telling of prosecutors who charged his father in February with fraud conspiracy, Adam Semprevivo appears more participant than pawn in the scheme that his father, Stephen Semprevivo, hatched with the consultant, William “Rick” Singer.

One example: At Singer’s instruction, the younger Semprevivo described a summer of “terrific success in doubles” in an August 2015 email sent to Georgetown’s tennis coach, according to an affidavit supporting charges against his father.

Adam Semprevivo’s lawsuit says descriptions of his tennis prowess were “misrepresentations.”

That coach, Gordon Ernst, later accepted a bribe from Singer, who pocketed $400,000 from Semprevivo’s father, according to charging documents filed against Ernst and Stephen Semprevivo. Ernst has been indicted on a charge of racketeering conspiracy. He has pleaded not guilty.

Stephen Semprevivo, an executive at an Agoura Hills company that offers outsourced sales services, has pleaded guilty to a fraud conspiracy charge. In his plea, he confirmed the government’s account of his misdeeds.

Prosecutors from the U.S. attorney’s office in Massachusetts recommend Stephen Semprevivo spend 18 months in prison.

Adam Semprevivo, 21, has not been charged with a crime or accused of wrongdoing. He is now suing for the right to transfer the credits he has earned over three years at Georgetown — and for which his family has paid $200,000 in tuition and fees — to a new school, where he can try to get on with his young life, his attorneys say.

Georgetown moved Wednesday to expel him, according to David Kenner, one of his attorneys, just 10 hours after his lawsuit was filed in federal court in Washington, D.C.

Kenner is now seeking an injunction to stop the school from expelling Semprevivo and voiding his credits. In the suit, Kenner argues Georgetown has denied Semprevivo due process rights enshrined in the university’s code of ethics, which constitute a contract between Georgetown and Semprevivo, a tuition-paying student.

Not until February, when his father was charged with a felony, did Adam Semprevivo learn of “allegations that his father had paid monies to Singer that were ultimately paid to Coach Ernst,” his lawsuit says.

Singer pleaded guilty in March to four felonies and admitted to masterminding the conspiracy.

The breadth of that conspiracy is outlined in an affidavit filed in support of charges against 33 parents, a 204-page document brimming with bold-faced names and snatches of conversation gleaned from court-approved wiretaps. One defense attorney grumbled that it was “chum in the water for a receptive press.”

Prosecutors devoted seven pages to supporting a fraud conspiracy charge against Stephen Semprevivo.

In August 2015, the affidavit says, Singer emailed Adam Semprevivo and his parents, and instructed the boy to forward several falsehoods onto Ernst, the Georgetown tennis coach.

Among the lies Semprevivo sent Ernst, according to the affidavit: “I have played very well with terrific success in doubles this summer and played quite well in singles too.”

Two months later, Singer emailed the boy and his father again. He needed to submit an essay to Georgetown, and Singer had written it for him. He emailed the essay to Adam Semprevivo and his father, according to the affidavit, which quotes from it.

“When I walk into a room, people will normally look up and make a comment about my height — I’m 6’5 — and ask me if I play basketball. With a smile, I nod my head, but also insist that the sport I put my most energy into is tennis.”

Semprevivo’s application to Georgetown contained other falsehoods, the affidavit says, including that he was named to the “Nike Federation All Academic Athletic Team” for tennis and that he played the sport all four years of high school.

His attorneys say he never signed the application, and thereby never attested to its truthfulness. Singer submitted it for him, they say, typing Semprevivo’s name into the signature block.

They fault Georgetown for failing to spot the “obvious inconsistency” in Semprevivo’s application: While he wrote his essay about tennis and described a decorated high school tennis career in his application, his transcript from the Campbell Hall school in Studio City showed he received credit not for tennis, but for basketball.

Just a “cursory examination … would have made it clear they were absolutely inconsistent with one another,” the lawsuit says.

Semprevivo was admitted to Georgetown after Ernst gave him a spot set aside for recruited tennis players, according to charging documents in Ernst’s criminal case and Semprevivo’s civil lawsuit against Georgetown. He never played tennis for the school after matriculating.

His father paid $400,000 to Singer, who in turn funneled some of the money to Ernst, prosecutors say. Between 2012 and 2018, they allege, Ernst reaped $2.7 million for sneaking at least 12 children of Singer’s clients into Georgetown.

The school has acknowledged being aware of “irregularities” in Ernst’s recruiting in December 2017, when it placed its 12-year tennis coach on leave after an internal investigation found he had violated admissions policies.

Because of that investigation, Semprevivo’s attorneys say, Georgetown either knew or should have known about issues with Semprevivo’s admission.

They accuse Georgetown of unjust enrichment in continuing to accept tuition payments from the Semprevivo family. Adam Semprevivo was never told his offer of admission could be revoked or his credits voided until this April, his attorneys say, when he was told the circumstances of his admission were being investigated.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.