Seaside mansion or public beach: Which will the California Coastal Commission save?

- Share via

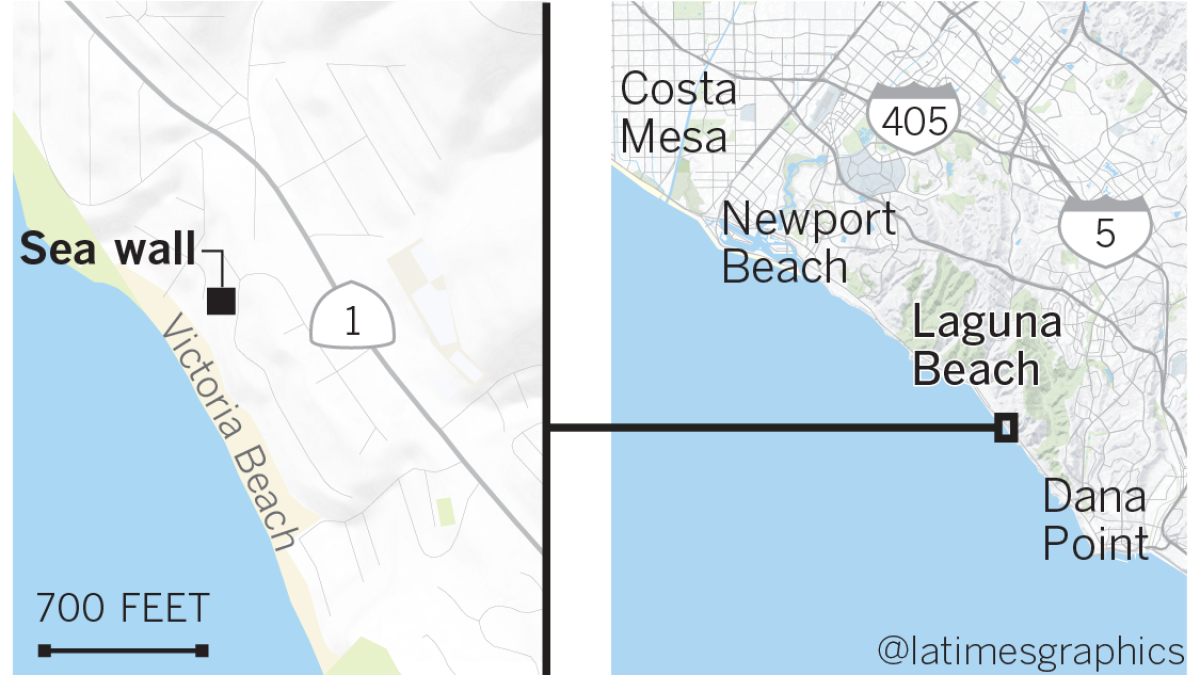

On a stretch of Laguna Beach where waves slam right onto white sand, a wall of steel and concrete interrupts the shoreline.

The sea wall exists to protect one beachfront home. Without it, the homeowners say, millions of dollars could be lost to the rising sea.

But the structure also inhibits the natural sand flow, according to coastal officials. So long as the wall remains, sand will continue to disappear in front of the home, washing away a section of what is known as Victoria Beach.

As more homeowners try to fight sea-level rise, California must pick a side: Protect private property or the public interest? Save a mansion or a beach for the people?

The California Coastal Commission on Thursday will decide whether to demand hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines from the homeowners and order the sea wall demolished — putting the house at greater risk of erosion. Such action would be rare for a commission usually mindful of walking the line between property rights and beach access.

In a preemptive lawsuit against the commission, the homeowners say the uncertainty over the sea wall has hurt them financially, hindering their ability to attract tenants willing to pay the monthly rent of around $70,000 or buyers willing to shell out the appraised price of $25 million. “The threats alone have had a devastating impact on the value and marketability,” the lawsuit said.

The facts, they say, are on their side. Also on their side are local planning officials, known in the area for helping owners develop and protect their coastal investments.

The commission’s decision could set off a domino effect along the coast, where new sea wall construction long has been limited to emergencies.

“If one homeowner wins, the whole state loses,” said coastal geologist Orrin Pilkey, a professor emeritus of Duke University who has studied disappearing beaches across the nation. “I’ve seen it happen in North and South Carolina, in Florida — if you give up the fight on one location, then you’re going to have to give up eventually on all locations.”

In 2015, Jeffrey and Tracy Katz, residents of the gated Lagunita community, bought the house next door for $14 million to ensure that no one would build a larger home on the lot and block their ocean views. The plan was to refurbish and sell, according to public documents, with a restriction that the 4,878-square-foot house could not be enlarged.

They tapped architect Jim Conrad — famed locally for his designs as well as his relationship with the city (not to mention his reality TV star daughter, Lauren Conrad). The house “was the shabbiest and oldest on the street,” Conrad said, according to a commission report. A sea wall, in his opinion, was the only way to protect the home, which juts farther seaward and at a lower elevation than surrounding properties.

The commission had previously acknowledged that same vulnerability.

In 2005, after a number of severe storms, commissioners granted an emergency permit for a temporary 80-foot-long sea wall. The next time “new development” occurred, the commission later ordered, the wall would have to come down.

By 2017, the couple had transformed the aging home into a glass mansion by the sea. The wall in front of it, still standing, also got bolstered. What exactly had happened — and whether it was legal — depends on who’s telling the story.

The Katzes brought on lawyer Steven Kaufmann after the commission started questioning the project. They all declined to comment, but said in letters to the commission that the sea wall did not have to come down until the house underwent a “major remodel”— which Kaufmann argued requires at least 50% demolition of the actual frame.

Although the exterior now looks fresh and modern, he said, the original beams and joists have not been replaced or reconstructed. Demolition amounted to 9.8% of the exterior elevations and 3.5% of the floor and roof.

Kaufmann, who previously served as a deputy attorney general for the commission, urged the panel to overrule a staff recommendation to tear down the wall. Staff is going “out of its way to skew the facts,” he wrote. “This minor remodel is no different than many others undertaken in the past and currently underway in the City of Laguna Beach.”

This reasoning got the blessing of city planners, the design review board and City Council. But a watchful neighbor, with the help of her own lawyer and coastal advocates, complained to state officials.

Much of the renovation was done in secret, covered up by construction drapes, they said, but virtually the entire house appeared redone.

Record requests unearthed emails from the city’s top building official, who said “the project is a 100 percent remodel and addition. … Every area inside and outside of the house has been rebuilt.” His interpretation was overruled by a zoning administrator who coastal officials later discovered had a personal connection to Conrad.

Gregory Pfost, Laguna Beach’s community development director, said he stands by the city’s decision and that the building official’s email was quoted out of context by those opposing the sea wall. He acknowledged that the zoning administrator and the Conrads are friends — “the awkward thing about small towns,” he said. But he said there is no conflict of interest in this case and has made it an internal policy to avoid situations that might appear otherwise.

“Curious things happen in this city with big money,” said Penny Elia, who has lived in Laguna for 33 years. “This cannot continue or the entire coast of Laguna Beach will soon be one solid sea wall with unpermitted mansions behind it.”

State enforcement officials say California’s Coastal Act is designed to make sure that doesn’t happen, but in the case of the Katzes, they went to great lengths to avoid the commission’s oversight.

In a more than 1,500-page report to commissioners, staff laid out their attempts to work with the owners, who “refused to stop construction, refused to consider any alternative protection methods other than the sea wall, and… sued the commission.”

If the Katzes were so intent on redoing the house, commission staff said, the smarter alternative — both for the long-term survival of the structure and for one of Laguna’s most popular beaches — would be to move the house farther inland. With sea levels rising, it is shortsighted to allow any new construction that needs a sea wall.

“This house was originally built in 1952. It was almost at the end of its expected economic life,” said Lisa Haage, the commission’s chief of enforcement. “But they’ve completely rebuilt it and are trying to start that clock over.”

In the last two years, the sea wall has trapped behind it about 18 dump trucks worth of sand now unable to erode and nourish the beach, Haage said. Last spring, staff found that little dry sand existed in front of the sea wall relative to the rest of Victoria, making it more difficult for beachgoers to cross in front.

Kaufmann said enforcement officials were judging by a handful of biased photographs rather than conducting a fair investigation. Citing technical consultants who analyzed the beach and property, he said that “there is no site-specific evidence that the newly constructed sea wall, which has the minimum footprint, had any impact on the beach.”

Even so, he said, the owners already have paid more than $63,000 in mitigation fees — a condition from the permit for a temporary sea wall — to help supply sand to the beach.

Advocates say each additional sea wall, however small, is taking more beach away from future generations.

“Every single decision made today is determining which beaches we want to save or not save,” said Mandy Sackett of the Surfrider Foundation. “And the only way we’re going to save our beaches is parcel by parcel, owner by owner, and unfortunately, each of them has been a fight.”

One recent morning, Sackett walked with Elia down Victoria Beach and noted the number of families on the sand. The beach, celebrated as the birthplace of modern skimboarding, draws locals and tourists alike with its rock pools and Instagram-famous “pirate tower.”

They gawked at the Katzes’ second home, freshly armored but sitting empty.

If the sea wall is allowed to stand, they said, what’s to stop the rest of the neighborhood from trying to do the same?

Tex Haines, a pioneer of modern skimboarding, thinks back to when his family and three others drove from Pasadena in the 1960s to escape the summer heat, renting a cottage for a few days right by Victoria’s public stairs.

“It was like the edge of the world, it was the most southern edge of Laguna,” he said. “Man, we were so lucky.”

He and friends took wooden boards and caught waves from the shore by racing into the break. As they grew older, they taught younger kids, who then passed the joy onward. Today, he sells boards for a living.

With each passing year, he has seen the homes grow larger and more expensive, the city pricing out many.

But the beaches remain free and for everyone, so long as the sand is still there.

Twitter: @RosannaXia

UPDATES:

2:15 p.m.: This article was updated to clarify the potential consequences of the demolition of the sea wall.

This article was originally published at 11:40 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.