LAPD searches blacks and Latinos more. But they’re less likely to have contraband than whites

- Share via

Los Angeles police officers search blacks and Latinos far more often than whites during traffic stops, even though whites are more likely to be found with illegal items, a Times analysis has found.

The analysis, the first in a decade to calculate racial breakdowns of searches and other actions by LAPD officers after they pull over vehicles, comes amid growing nationwide scrutiny over racial disparities in policing.

The Times obtained the data used in its analysis under a new California law targeting racial profiling that requires the LAPD and other agencies to record detailed information about every traffic stop.

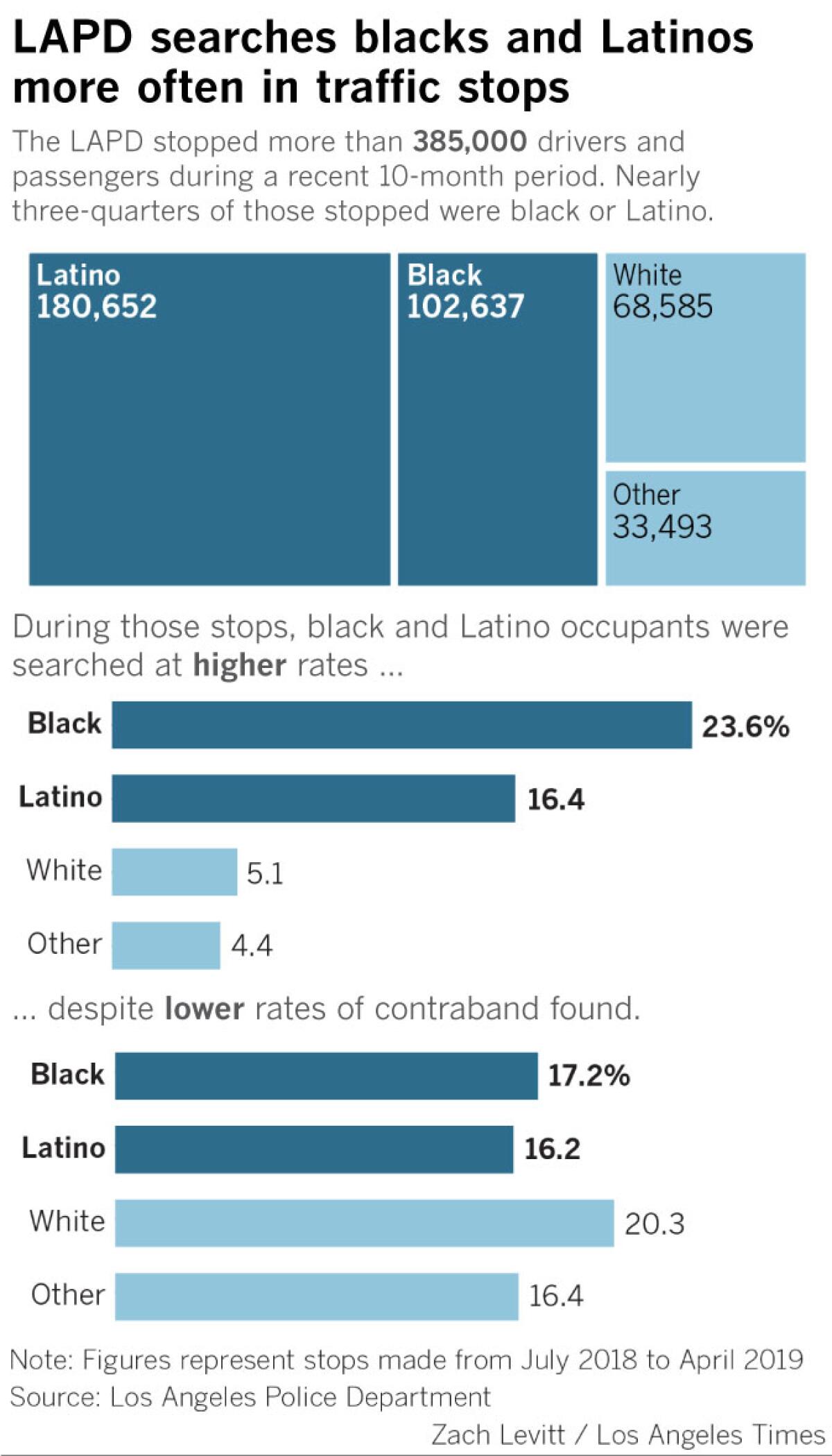

The Times analysis found that across the city, 24% of black drivers and passengers were searched, compared with 16% of Latinos and 5% of whites, during a recent 10-month period.

That means a black person in a vehicle was more than four times as likely to be searched by police as a white person, and a Latino was three times as likely.

Yet whites were found with drugs, weapons or other contraband in 20% of searches, compared with 17% for blacks and 16% for Latinos. The totals include both searches of the vehicles and pat-down searches of the occupants.

Racial disparities in search rates do not necessarily indicate bias. They could reflect differences in driving behavior, neighborhood crime rates and other factors.

But the lower contraband hit rates for blacks and Latinos raise serious questions about the law enforcement justification for searching them more often than whites, criminologists said.

Stop-and-search statistics are commonly used by law enforcement agencies to gauge the disparate racial impacts of policing. The U.S. Department of Justice sometimes requires agencies with civil rights issues to collect and analyze the data.

But the LAPD’s constitutional policing advisor said this type of analysis does not account for the complexities of a police officer’s decisions in sizing up a situation and deciding how to deal with the people in a vehicle. Officers receive training on their own implicit biases and have a lawful basis for every stop and search they perform, said the advisor, Arif Alikhan, who recently left the LAPD.

Alikhan noted that the analysis includes stops where officers exercise little discretion and racial bias is less likely to be a factor, such as a search during an arrest.

“We don’t pull people over based on race. We’re not supposed to do that,” Alikhan said. “It’s illegal. It’s unconstitutional. And that’s not the basis [on which] we do it.”

To some community activists and academics, the numbers heighten concerns that the LAPD could be singling out blacks and Latinos for invasive searches, damaging relationships with minority residents that the department has worked to strengthen since the dark days after the 1992 riots.

“Even if you have reasonable suspicion or probable cause, if you’re not producing arrests that go directly to the highest levels of public safety, all you’re doing is dragnetting, with a very high cost in trust,” said civil rights attorney Connie Rice, a longtime LAPD critic who in recent years has worked with the department on reforms.

Mayor Eric Garcetti called the Times analysis “both important and timely” and said he is committed to “helping the LAPD make forward progress on issues of race and community relations.”

“I look forward to our Police Commission and department leaders using this information to improve best practices, and I expect the department to work consciously and even-handedly to earn the trust of every Angeleno, every day, with every interaction,” Garcetti said in a written statement.

LAPD Chief Michel Moore declined requests for an interview. He said in a written statement that the Times analysis does not tell the complete story because it does “not define or describe the circumstances of each stop or search.”

The statement noted that the LAPD does not tolerate racial profiling and will discipline officers if necessary.

“We strive to ensure our stops and searches are lawful and done in a manner that builds community trust,” Moore said in the statement.

The new findings follow a Times article published in January showing that the LAPD, including its elite Metropolitan Division, stopped black drivers at much higher rates than their share of the population.

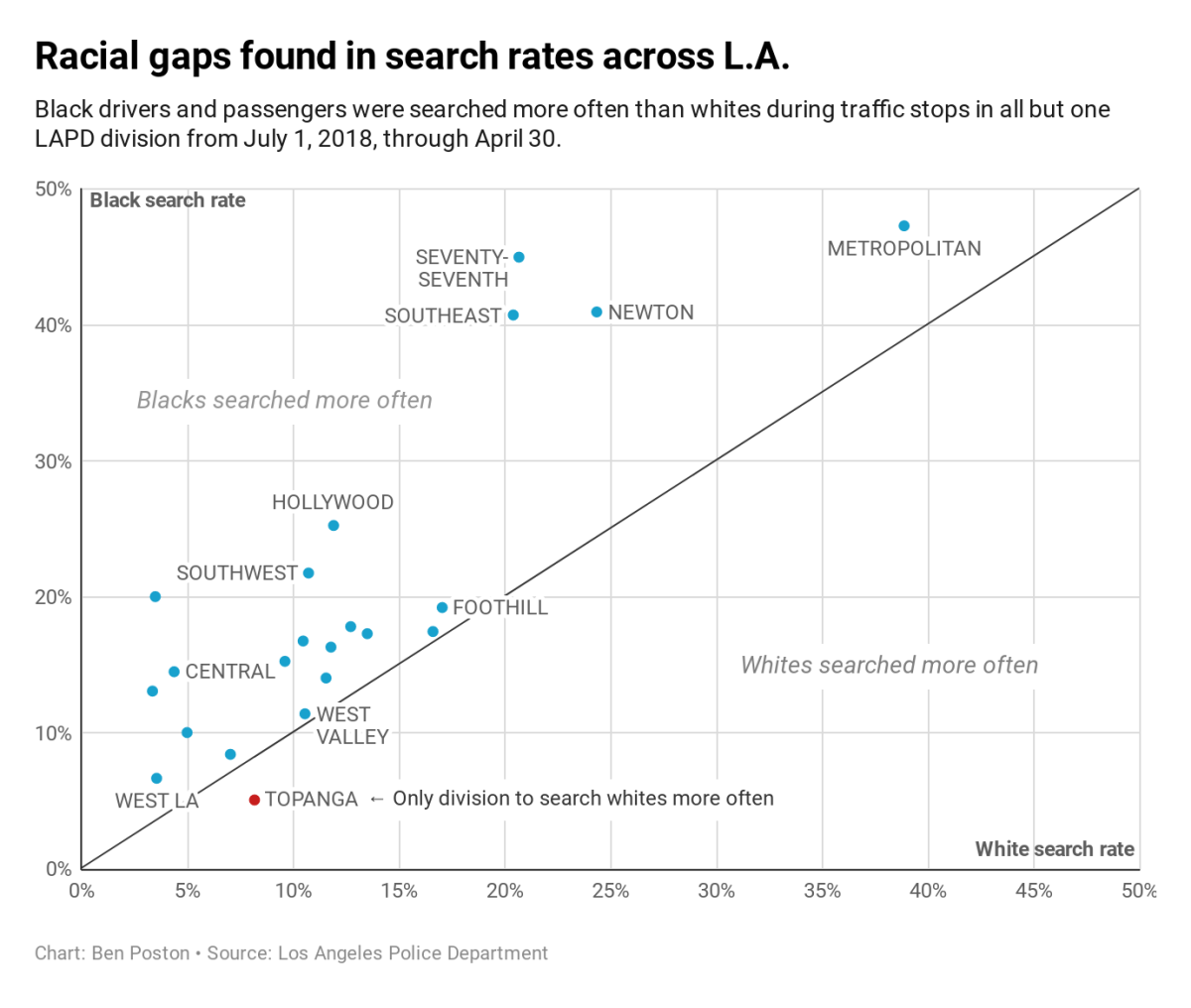

According to the Times analysis of the new state data, black and Latino drivers and passengers were searched more often than whites in almost every part of the city.

Blacks and Latinos were more than three times as likely as whites to be removed from the vehicle and twice as likely to either be handcuffed or detained at the curb, the Times analysis found.

About 3% of blacks and Latinos stopped by the LAPD were arrested, compared with 2% of whites.

Overall, LAPD officers found contraband in 17% of the searches they performed. Most of the contraband was drugs or alcohol, while 9% was firearms.

::

The racial disparities begin when LAPD officers decide which cars to pull over. The Times analysis found that black and Latino drivers were stopped at higher rates than whites.

Of the more than 385,000 drivers and passengers pulled over by the LAPD from July 1, 2018, through the end of April, 27% were black, in a city that is about 9% black. About 47% of those pulled over were Latino, which is roughly equivalent to their share of the population. About 18% of those stopped were white, when 28% of the city is white.

Asians, not including those of South Asian descent, made up about 4% of those stopped and 11% of the population. The LAPD searched 2% of Asian drivers and passengers who were pulled over.

An equipment violation, such as a broken taillight or tinted windows, was listed as the reason for more than 20% of vehicle stops involving blacks and Latinos, compared with 11% of stops involving whites, according to the Times analysis.

Such violations can serve as a pretext for officers to look for more serious wrongdoing. Pretextual stops are legal but have been criticized by scholars and civil rights advocates as giving too much license to law enforcement to operate on instinct rather than evidence.

In response to the earlier Times report showing similar racial disparities, Garcetti ordered the department to scale back vehicle stops. Through August, the number of stops performed by the LAPD was down 11% compared with the same period last year, while stops by Metropolitan Division were down by 45%.

At a Police Commission meeting on Tuesday, Moore highlighted the overall decrease in vehicle stops, saying it was a response to residents’ concerns about the disparate impact of traffic stops, particularly in South Los Angeles.

He said he will soon announce changes to Metro’s crime suppression units, which community groups have demanded be withdrawn from South L.A.

Moore declined to elaborate on the changes, but he has previously spoken about possibly switching Metro officers from unmarked cars to black-and-whites as well as further reducing the reliance on vehicle investigative stops.

:

As night fell on South L.A. on a recent evening, two LAPD officers stopped a white Buick Regal.

They told the people in the car to get out. Then they spotted a handgun on the floor of the front passenger side.

“I know there’s a gun in the car. Do you mind if we search the car?” Officer Charles Kumlander asked the two young black men and two young Latina women who stood facing a fence in handcuffs as a Times reporter and photographer watched. One of the men nodded.

Kumlander put the gun, along with a blue bandanna, on the hood of the car. Bullets spilled out. He fumbled through the women’s purses.

The officers concluded that the gun belonged to the male passenger and let the others go.

“You shouldn’t be driving around South L.A. with a gun wrapped in Crip colors,” Officer Colt Haney admonished the women, who were from San Bernardino. “That’s how people get shot.”

LAPD officials did not allow a Times reporter to speak to the officers, who were with the 77th Street Division’s gang unit. They briefed their supervisor, Sgt. Mario Cardona, on why they stopped the car at West 54th Street and South Vermont Avenue.

According to the officers, the front passenger was not wearing his seat belt and bent down to put something between his legs. The car’s registration tags were also expired.

The car had tinted windows and was in a known gang area, and there were multiple people inside. The officers believed there was a safety risk and ordered the driver and three passengers to exit the vehicle. The gun was in plain view, so they could legally confiscate it and search the rest of the vehicle.

Demographically, the LAPD closely mirrors the city: 49% of officers are Latino, 10% are black, 31% are white and 10% are Asian, according to department figures.

As they cruise the streets of L.A., officers should be curious about what they see, Cardona told a Times reporter, likening the process to casting a line without knowing if you’ll hook a small or big fish.

If a person seems out of place — for example, if he is wearing a hat associated with one gang but is on another gang’s turf — an officer should find out who that person is, he said. But racial profiling is never involved, he added.

“Are we stopping you just because you’re black? No,” Cardona said. “You ran the light, so we’ll do a traffic stop and figure out who you are.”

LAPD officers found guns in less than 2% of searches they conducted, according to the Times analysis. More than 4 times out of 5, they came up empty-handed — no drugs or weapons.

::

Citywide in 2018, 43% of violent crime suspects were black and 40% were Latino, according to LAPD statistics. Experts say this does not justify the disparate search rates, because contraband is found less often on the groups that are searched more often.

“At its simplest level, it appears that blacks and Latinos are being subjected to a lower threshold of suspicion in order to be searched,” said Jack Glaser, a professor of public policy at UC Berkeley who has studied traffic stop data.

Glaser said the 24% search rate for African Americans raises questions about whether LAPD officers are targeting them because of their race.

“If you are searching a quarter of the people you’re stopping, you’re looking to search people,” he said. “You’re not just pulling people over for running stop signs and then happening to see they have a gun-shaped bulge in their pocket.”

Lorie Fridell, a criminology professor at the University of South Florida who authored a pioneering study on stop data, said the lower contraband rates for whites are a “warning signal” and should be reviewed by LAPD officials.

“Even though we can never prove or disprove bias, they are a strong red flag for unjustifiable disparity that requires an agency to at least take a closer look at the search practices,” said Fridell, who has conducted federally funded training on bias at police departments across the country.

In addition to the traditional analysis involving racial breakdowns of stops and searches, The Times used a statistical model called a “threshold test” in collaboration with the Stanford Open Policing Project. The model weighs search rates and contraband recovery rates to determine how much evidence officers require before conducting searches of different racial groups.

The Stanford researchers found that the LAPD generally searched blacks and Latinos based on less evidence than whites.

This was true even when excluding “non-discretionary” searches — including those conducted because of an arrest or as a condition of probation or parole — as the primary reason for the search. In those cases, officers have explicit permission to search, so racial bias is unlikely to be at play, versus when the search is more of a judgment call, experts said.

Even if every search has a legal basis, it is unconstitutional to apply a different search standard to African Americans and Latinos than to whites, said Peter Bibring, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Southern California and director of police practices for the ACLU of California.

“If that’s the kind of policing that they think fits the white community in Los Angeles, if that’s the kind that’s least intrusive, that’s the kind of policing that every Angeleno deserves,” he said.

:

For people who have been stopped and searched by the LAPD, the experience can be humiliating.

In November 2017, Bryant Mangum was driving home in his white BMW with tinted windows when he was pulled over by LAPD officers at gunpoint.

They patted him down and told him to stand facing a fence with his hands behind his back, he told The Times.

While one officer searched the car, the other asked whether he had guns or drugs, whether he was in a gang and how he could afford a BMW.

The officers didn’t say why they pulled him over and didn’t ask permission to search the car, Mangum said. They let him go without a ticket or a warning.

Mangum, 37, is a warehouse foreman who owns a home a block away from East 99th and South Main Streets, where the incident occurred. He has a criminal record, mostly for vandalism from his days as a guerrilla graffiti artist, but his last conviction was in 2006, court records show.

When he first bought the BMW and it still had paper plates, he was pulled over 10 times in one month, he said.

Mangum believes that officers see a nice car driven by a black man and want to investigate whether he is a gang member or drug dealer. He doesn’t ask why he is being stopped or searched, since officers have bristled at questions in the past.

“It’s very traumatic — I don’t like to drive my car at night,” Mangum said. “I can’t enjoy it where I live. I’m more worried about cops than criminals.”

In Van Nuys, Leo Hernandez said he was stopped by LAPD officers twice in 2015.

Once, the officers told him his Honda Civic was a model often stolen in the area. The other time, they said his tinted windows were too dark and the rosary beads on his mirror illegally obstructed his view.

Both times, the officers asked to search his car, Hernandez said. He agreed, and they found nothing.

“I asked, ‘Why am I being stopped? Is it because of how I look?’” Hernandez, 36, who is Latino and works part time for the city’s Recreation and Parks Department, said of the tinted windows stop, which resulted in a ticket. “Of course it felt like profiling.”

::

The gaps in search rates between blacks and whites in Los Angeles are wider than those found in other major California cities such as San Diego and Oakland, but smaller than San Francisco, according to the most recent reports available.

Policing experts acknowledge the limitations of the data but say that local law enforcement leaders should take it seriously.

The LAPD was required by a federal consent decree to collect detailed stop and search data but cut back after the decree was lifted in 2013. Until the new state law took effect last July, LAPD officers collected basic information on vehicle and pedestrian stops but almost nothing about searches.

“They have a responsibility to say, ‘Here’s the nature of the stop data, and here’s the nature of the crime in this area,’” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, which researches and recommends policies for police agencies. “I’m not saying the stops are wrong, but they’re a starting point for a discussion about the nature of crime in that neighborhood and what does that say about the strategy?”

In response to a lawsuit by the ACLU, the New York City Police Department drastically cut back on stopping and frisking black and Latino pedestrians. The Oakland Police Department has decreased its vehicle stops by nearly half since 2015.

Oakland police officers still stop and search blacks at higher rates than other races. But fewer residents are inconvenienced by traffic stops, while crime has decreased in many key categories.

Pretextual stops are more of a fishing expedition than a targeted crime-fighting effort, according to Oakland police leaders, and officers have been instructed to use them sparingly.

“We’ve reduced our footprint in the community. And that also heals relationships,” said Police Chief Anne Kirkpatrick. “You’re not stopping everybody with a broad net.”

Times staff writer Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

The data, code and documentation for this story are available on Github.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.