Metro’s sales tax could reduce your time stuck in traffic by 15% — but not until 2057

- Share via

As cars and trucks crawl along a congested Southern California freeway, a dark-haired driver rests her head on her hand in frustration.

The narrator’s voice breaks in with a tantalizing suggestion: If Los Angeles County voters approve a tax increase for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority on Nov. 8, they will reduce their time stuck in traffic by 15% a day.

For the record:

6:58 p.m. Jan. 23, 2025An earlier version of this article said Measure M would lead to transportation investments of $210 billion over four decades. The correct figure is $120 billion.

What the advertisement doesn’t mention is that Measure M’s promised traffic relief would not arrive until 2057.

The analysis that the ad cites did not conclude that traffic will flow faster in 2057 than it does today, nor that traffic will noticeably improve over the next few years. Barring a recession or a major increase in the cost to drive and park, experts say, congestion in Los Angeles will continue to get worse.

“We think our ads are very clear about the fact that Measure M will reduce traffic, and the alternative will not,” said Yusef Robb, a spokesman for the Yes on M campaign, which funded several ads running in English and Spanish on cable and local channels.

Officials at Metro, who are barred from advocating for the measure, offered a series of lukewarm assessments about the ad’s claims that an estimated $120 billion in transportation investments over four decades “will reduce the time you’re stuck in traffic by 15% a day.”

“It’s not exactly right,” said David Yale, a senior executive officer, “but it’s not a big leap of faith to dumb it down, if you will, like that.”

Said Metro spokeswoman Pauletta Tonilas: “There’s a whole lot more behind it. It doesn’t get into minutiae.”

Our ads are very clear about the fact that Measure M will reduce traffic, and the alternative will not.

— Yes on M spokesman Yusef Robb

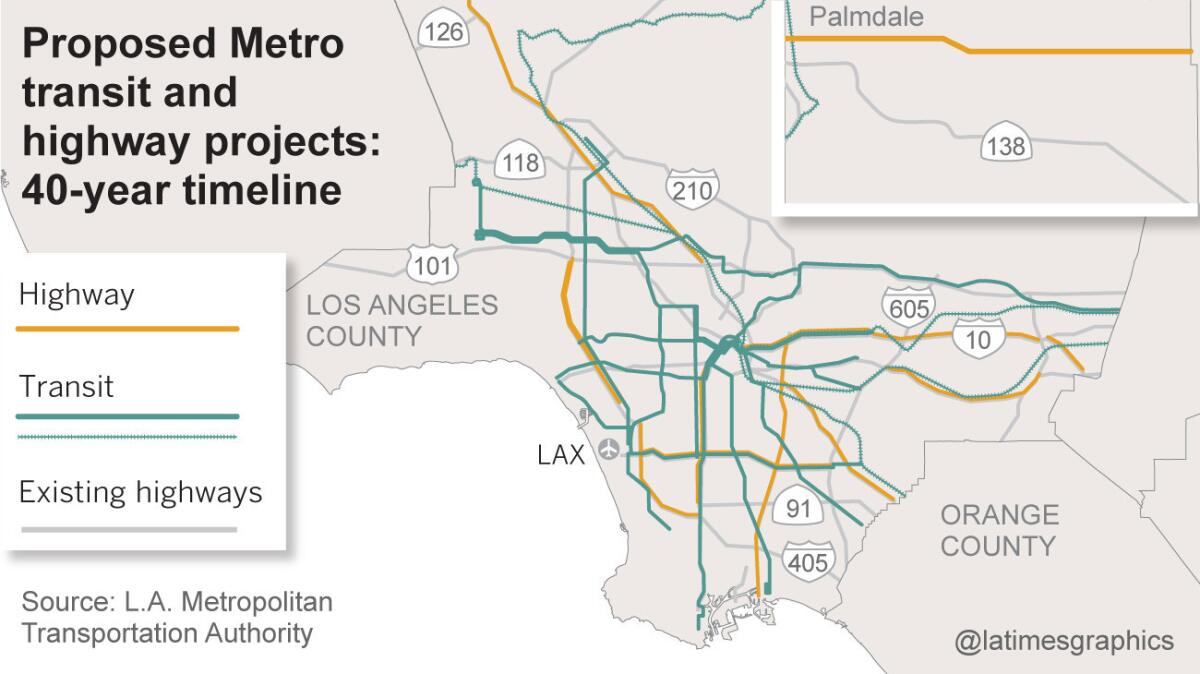

Earlier this year, Metro hired Cambridge Systematics to examine what effect 10 highway projects and 15 new transit projects proposed in Measure M would have on congestion over time.

Without any upgrades to freeways or rail lines, the firm found, the 12.5 million people projected to be living in the county in 2057 will spend nearly 5.5 million hours delayed in traffic each day.

If Metro finishes the two dozen biggest highway and transit projects listed in Measure M, researchers found, the daily hours of delay would drop 15% to 4.6 million hours.

The 15% decrease would apply only to the time that drivers are delayed by slow traffic, not the total time spent commuting, Metro officials said. They added that the finding should not be applied to individual drivers because commutes can vary dramatically by location and time of day.

Traffic is likely to get worse whether or not rail is built.

— INRIX economist Bob Pishue

Although such studies use the best information available, the results are still estimates. There are many unknowns, from where Angelenos will live and work in four decades to what effect autonomous vehicles could have on traffic.

“It’s commonplace for ballot initiative campaigns to hire their own experts, much like defense attorneys, who come up with results that prove their thesis,” Robb said. “We’re proud that our ads rely on independent, credible and conservative traffic-reduction estimates.”

The analysis did not take into account the estimated $22.5 billion that would be allocated for transportation improvements in cities, such as pothole repairs and left-hand turn signals, Robb added.

Measure M would raise the county’s base sales tax rate by a half-cent in 2017 and would increase to 1% in 2039 after another half-cent tax expires. It requires a two-thirds’ majority to pass, always a high hurdle.

The measure, which Metro says would raise $120 billion in revenue over its first four decades, would fund more than a dozen new rail lines and extensions, including a rail tunnel through the Sepulveda Pass and lines to Pacoima, Artesia, Claremont and Torrance.

Emphasizing traffic relief to sell one of the most ambitious transit expansion plans in modern history underscores the political reality of a car-choked region in which four in five residents drive to work.

The lion’s share of Metro’s funding, and the capital for the construction of the region’s 105-mile passenger rail network, come from three half-cent sales taxes approved in 1980, 1990 and 2008. All were advertised with drivers in mind. (The 2008 tax was dubbed Measure R, for “traffic relief.”)

Earlier this year, Metro launched a major advertising campaign on their website and on billboards across the county, reminding commuters that “Metro eases traffic.”

Transportation officials say a network of new lines, as well as more transfer points within the system, will dramatically increase transit ridership and reduce congestion on the freeways — a claim that researchers have contested.

“Traffic is likely to get worse whether or not rail is built,” said Bob Pishue, a senior economist at traffic data company INRIX. In some cases, he said, congestion may be slightly less bad if a rail line is built.

Voters who aren’t regular bus or rail riders often support transit initiatives because they hope it will make their own drive easier, Pishue said.

But if space on a freeway opens up, another car typically fills it. So-called “induced demand,” coupled with more people and more jobs, makes it difficult to reduce congestion in major cities over time without charging people more to drive.

Transit is trying to achieve a lot of other things other than reducing the hours of delay in traffic.

— Metro senior executive officer David Yale

Aggressive tolling could immediately reduce L.A.’s congestion, Yale said, and could lead to a decrease in traffic over the next few years. But, he added, “those mechanisms are so unpopular and so hard to implement that we just don’t see it happening.”

When the first phase of the Expo Line opened between downtown Los Angeles and Culver City in 2012, officials heralded it as a way to reduce traffic on the 10 Freeway.

While the $1.5-billion route encouraged transit use and helped residents nearby reduce their daily driving, the Expo Line did not have a significant impact on speeds on the 10 or on major streets nearby, USC researchers found.

The findings were a reminder, researchers said, that politicians should be more realistic in how transit is sold to the public.

“Most rail transit should be seen as an alternative to congestion, rather than the relief for congestion,” Pishue said.

Measure M tax revenue would subsidize fares for seniors, students and the disabled, and new rail construction could help commuters add walking and biking into their daily routines, Yale said.

In the Metro-funded study, researchers noted that Measure M would make rail and bus rapid transit available to more job centers and to more transit-dependent Angelenos.

“Transit is trying to achieve a lot of other things other than reducing the hours of delay in traffic,” Yale said. “This system will have more options.”

ALSO

Homeowner feared dead after flames destroy hillside home in Mt. Washington

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.