L.A. officials present a plan for renters and landlords to split the costs of quake retrofitting

- Share via

Since Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti proposed the most sweeping earthquake-retrofitting laws in California history last year, the big question has been who will pay for the costly upgrades.

Many buildings that are vulnerable to quakes are older apartments, and there has been growing debate about passing on the costs to tenants in a city that already has some of the nation’s highest rents.

On Wednesday, city officials proposed a compromise in which building owners and renters would share the financial burden equally. Under the plan, tenants would face rent increases over a five- to 10-year period, with a maximum increase of $38 per month.

There are more than 1,000 concrete buildings and at least 12,000 wooden apartments across Los Angeles that city leaders want retrofitted. Experts said these structures face the greatest risk of collapse in a major earthquake.

Backers of the retrofitting plan say that the cost-sharing proposal offers a framework to move forward. Past efforts to require property owners to strengthen these buildings died over the question of costs, which is proving to be Garcetti’s biggest challenge in getting his ambitious seismic plan through the City Council this fall.

The cost of retrofitting varies widely. Strengthening wooden apartments with weak first floors could cost as much as $130,000. Upgrading larger concrete buildings will probably run into the millions.

Tenants have worried that owners would be allowed to pass on all the retrofitting costs through huge rent increases.

Under current housing laws, which have rarely been used for seismic retrofitting, property owners technically could do so through a rent increase of as much as $75 per month.

In 2013, San Francisco required owners to retrofit vulnerable wooden apartment buildings but allowed the costs to be passed on to renters — even those protected by rent control — over a 20-year period. Exceptions have been made to help ease the burden on renters with the lowest incomes.

Councilman Gil Cedillo, the head of the City Council committee that reviewed the 50-50 proposal Wednesday, said that the city must push ahead with a mandatory retrofitting law.

But he said the way to share costs is a question that required further review. He emphasized, however, that tenants and property owners are much closer to an agreement now than a few months ago.

“We walked in here, several months ago, and everybody was very upset. The heat in this room was incredible,” said Cedillo, who vowed in January that Los Angeles would not follow in San Francisco’s footsteps and make tenants pick up all the costs. He asked city officials to recommend other options.

Housing officials held four meetings with tenant and property owner groups, but were unable to come to a consensus. However, Anna Ortega of the housing department said, both sides agreed that retrofitting was vital to the safety of the city’s residents and the preservation of Los Angeles’ housing stock, and that the costs should be somehow shared.

“We agreed on a number of issues, but we could not, not surprisingly, come to agreement” on cost-sharing, said Larry Gross, executive director of the tenant advocacy group Coalition for Economic Survival.

Gross said that any rent increase will be tough on tenants, but that Wednesday’s proposal “at least attempts to lessen that burden.” He said he supports a 10-year period but is concerned about how accumulated interest on the retrofitting costs will be factored into how much renters will pay. Other tenant advocates were concerned that the rent increase would be permanent, and wondered whether owners would be allowed to stack the cost of additional rehabilitation projects on top of any seismic work.

Some also argued that Los Angeles’ lowest-income tenants should be exempted from the rent increases.

Property owners had a different set of concerns.

They worried that they wouldn’t be able to obtain loans if they couldn’t demonstrate that their properties could provide enough income to pay back the borrowed funds.

Will $38 a month be enough for lenders to agree to a loan, asked Beverly Kenworthy, executive director of the Los Angeles division of the California Apartment Assn. She argued that not enough research with lenders has been done to address that concern.

Jim Clarke of the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles added that city officials should first look into providing more financial aid, such as a break on expensive building permit fees or property tax rebates.

“If we can get these costs down... it might be acceptable on both sides,” Clarke said.

Cedillo said he hopes officials will find additional financing options to reduce the overall burden of retrofitting before finalizing a way to spread the costs among tenants and owners.

“We’re not going to decide the split until we know how much money we’re dividing,” Cedillo said.

Options could include low-interest loans and tax breaks to owners who retrofit. Much hope has been placed on a state bill that would give owners a tax credit worth 30% of the retrofitting costs. The bill, introduced by Assemblyman Adrin Nazarian (D-Sherman Oaks), passed the Senate this month and is awaiting Gov. Jerry Brown’s consideration.

Cedillo and his colleagues are also expanding a program that provides private loans for retrofitting that would be paid back through a temporary, voluntary increase on their property tax bill.

Officials have known for decades about the dangers of buildings that are vulnerable in quakes, but concerns about costs thwarted earlier efforts to identify and force property owners to retrofit their buildings.

More than 1,000 concrete buildings across the city may be at risk of collapsing in a big earthquake, a Times analysis found. In 1971, the Sylmar earthquake brought down several concrete structures, killing 52. A 2011 quake in Christchurch, New Zealand, toppled two concrete office towers that crushed more than 130 people.

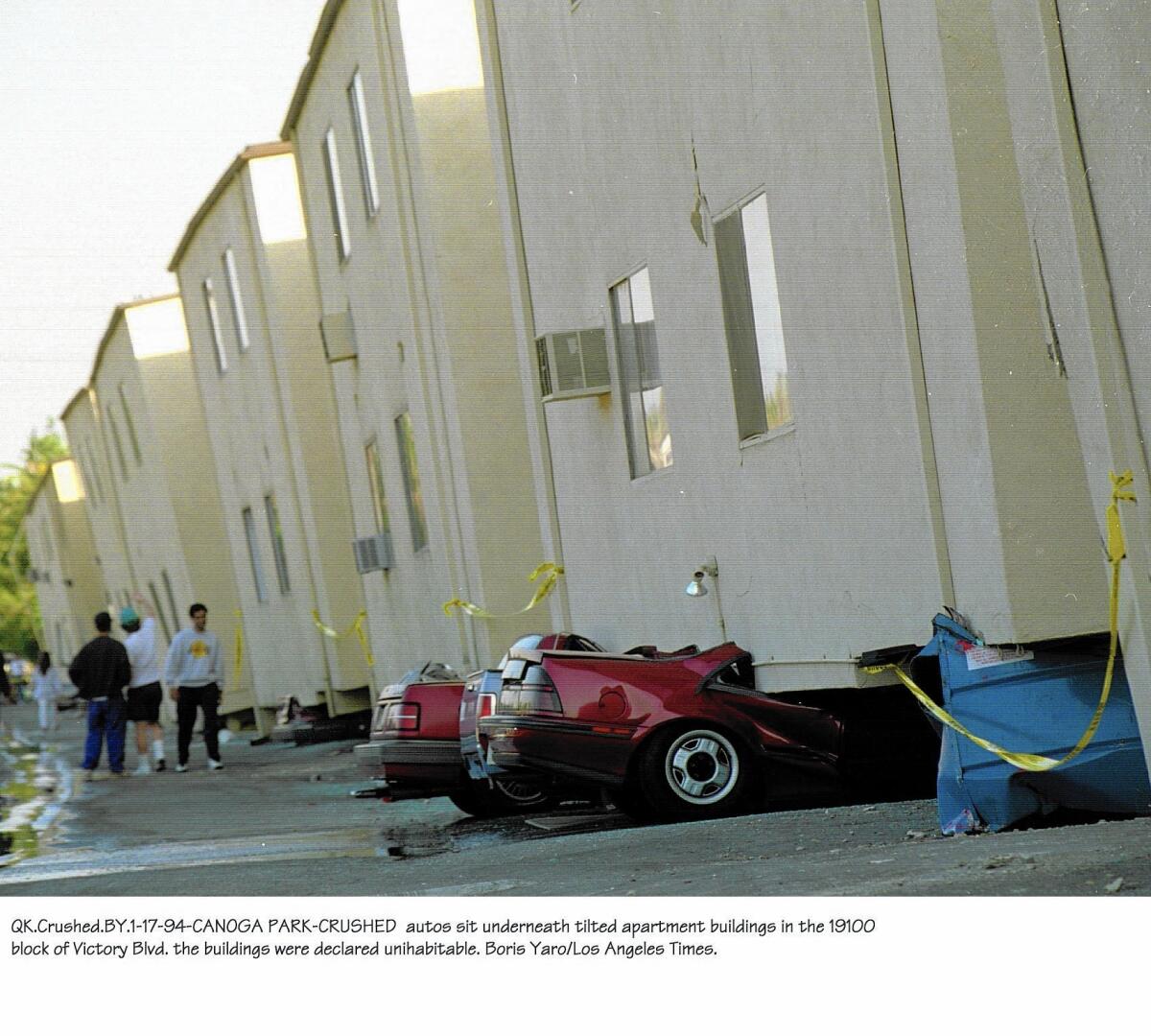

Wooden “soft-story” apartments also have a history of failing during big quakes. Sixteen people were killed when one such building pancaked in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Cedillo’s committee instructed the staff to begin drafting the law that would call for mandatory retrofitting of these buildings. Further discussion on how to split the costs between tenants and owners will continue at a later date, he said.

Councilman Felipe Fuentes also said the city was making progress. “I hate to admit it, but it seems like when everybody hates things equally, we’re getting closer to the final product.”

Follow @RosannaXia on Twitter for more news about seismic safety.

ALSO:

Looks like the tsunami from Chile spared Southern California

At L.A. summit, Biden says it’s time to ‘end debate’ on climate change

Second LAPD shooting in less than 24 hours leaves man critically wounded

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.