For first time, more L.A. residents believe new riots likely, new poll finds

Could another event like the L.A. riots happen again? (April 26, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

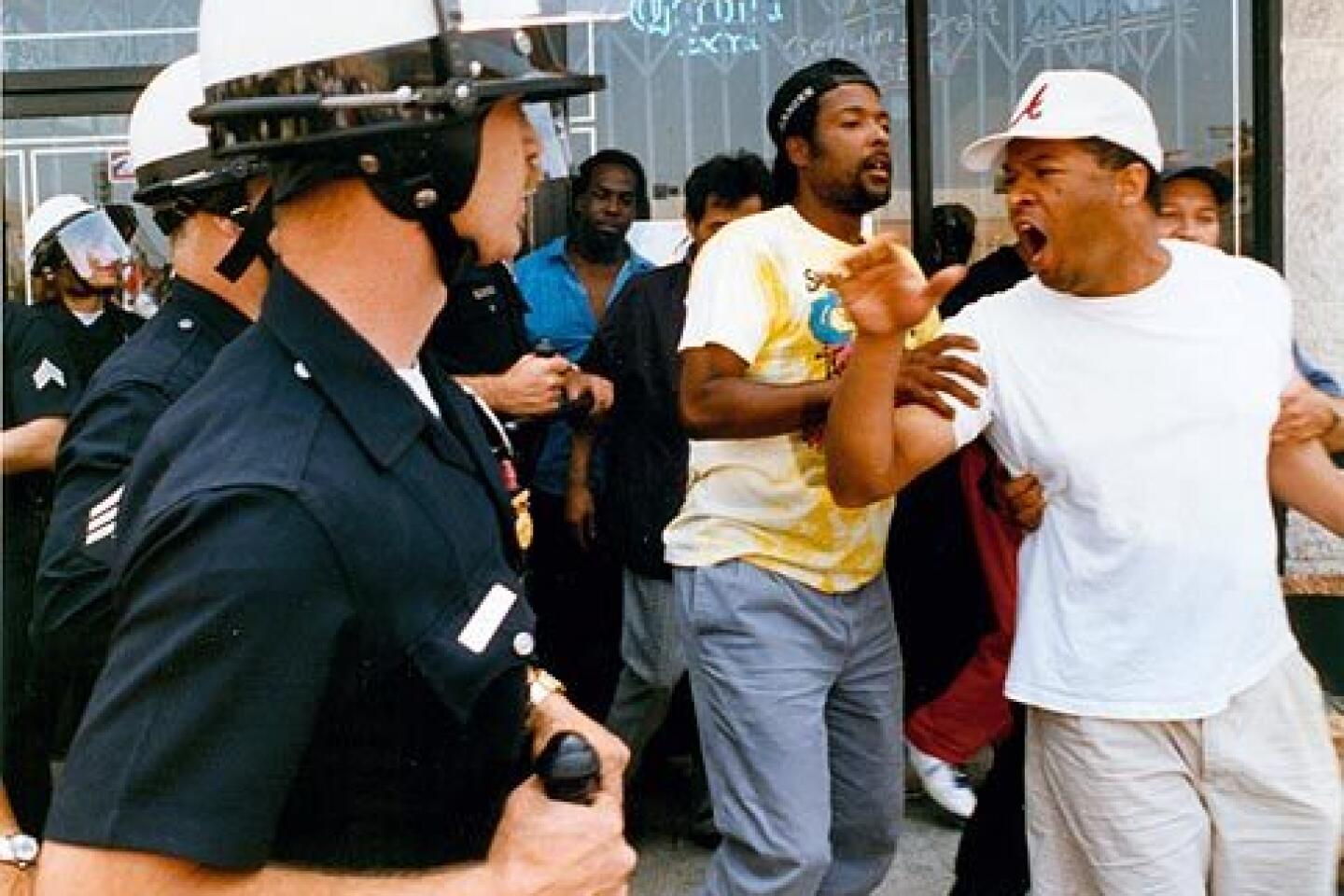

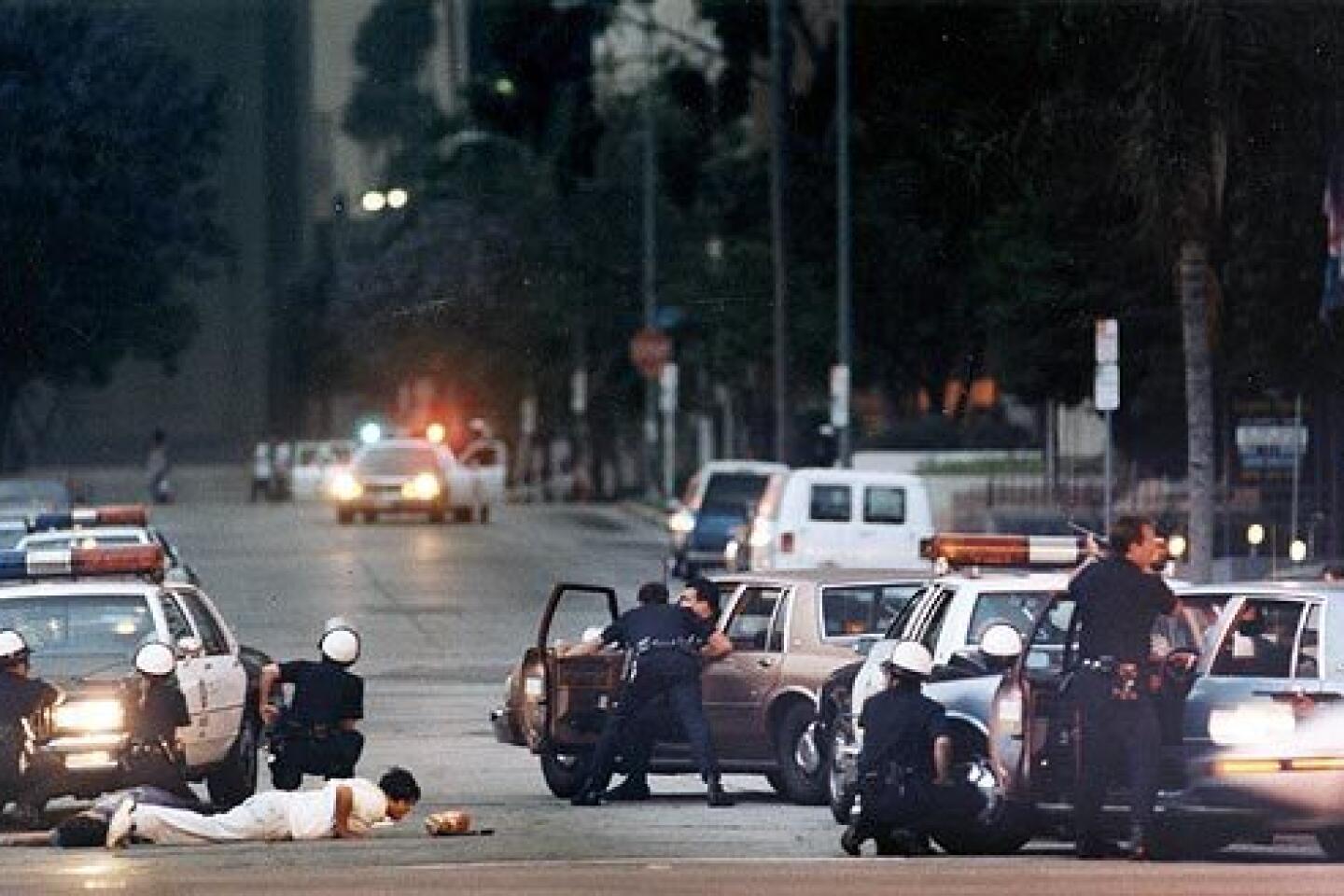

For Nicole Cuff and her friends, the 1992 Los Angeles riots used to feel like a piece of history, told in old stories by their parents or discussed and analyzed in school.

Recently, though, it’s started to feel much more real to her — like something that could happen again in the near future.

Cuff, a coordinator at an entertainment management company who is half black and half Filipina, said her feelings come in part from several years of headlines, viral videos of police force and Black Lives Matter protests over police shootings of African Americans.

“It evokes some unfelt anger that hasn’t been tapped into,” said Cuff, 26, who has a diverse group of friends who have become much more politically engaged in the last few years. “When nobody pays a price for it … it could set people off.”

Her view reflects what researchers who study public attitudes about the L.A. riots say is a distinct shift: For the first time since the riots, there is an uptick in the number of Angelenos who fear that another civil disturbance is likely, according to a Loyola Marymount University poll that has been surveying Los Angeles residents every five years since the 1992 disturbances.

Nearly 6 out of 10 Angelenos think another riot is likely in the next five years, increasing for the first time after two decades of steady decline. That’s higher than in any year except for 1997, the first year the survey was conducted, and more than a 10-point jump compared with the 2012 survey.

Young adults ages 18 to 29, who didn’t directly experience the riots, were more likely than older residents to feel another riot was a possibility, with nearly 7 out of 10 saying one was likely, compared with about half of those 45 or older. Those who were unemployed or worked part-time were also more pessimistic, as were black and Latino residents, compared with whites and Asians, the poll found.

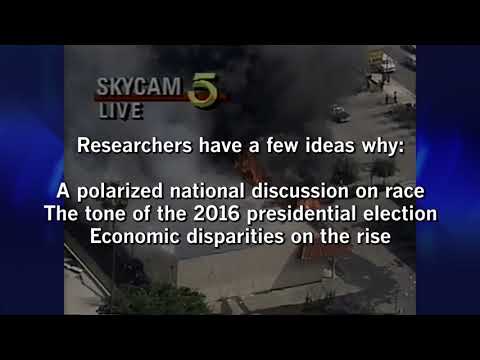

Researchers theorized that the turnaround may be linked to several factors, including the more polarized national dialogue on race sparked by police shootings in Ferguson, Mo., and elsewhere, as well as by the tenor of last year’s presidential election. Moreover, many parts of L.A. still suffer from some of the economic problems and lack of opportunities that fueled anger before the riots.

“Economic disparity continues to increase, and at the end of the day, that is what causes disruption,” said Fernando Guerra, a political science professor who has worked on the survey since its inception. “People are trying to get along and want to get along, but they understand economic tension boils over to political and social tension.”

Although the city’s unemployment rate last year was about half of what it was in 1992, the median income of Angelenos, when adjusted for inflation, is lower than it was around the time of the riots. Poverty rates still remain high at 22%, comparable with the years preceding the riots.

Jamal Jones, a Leimert Park resident and community leader who grew up spending a lot of time in South L.A., said if the tension revolved around race 25 years ago, lately, it’s been along economic lines related to housing and affordability, with residents feeling the pain across racial groups.

Jones, who is 39, said people like him who remember what it was like around the time of the riots know that the type of civil unrest that took place in 1992 wasn’t ultimately effective in fixing underlying social problems. Those who are younger, he said, might not have the same perspective, and want to act immediately on the news and images they’re seeing.

“We’ve done that, that’s been the strategy for so many years. We’re going to have to mobilize in a different way,” he said. “The young lions are getting all this fuel. We have to be careful, we’ve got to channel that energy in the right direction.”

Despite the increased concern about another riot, the survey found most Angelenos continued to feel optimistic about race relations in the city, with three-quarters of respondents saying different racial and ethnic groups got along well.

Alberto Nava, 38, said he felt both race relations in the city and police treatment of minorities had vastly improved since the time of the riots. But the new political climate and the election of President Trump made it feel like another riot may be brewing, he said. His friend Marco Delgado, 45, with whom he was lunching in East L.A., agreed and said social media had also changed the speed at which people react to high-profile incidents.

“People get emotional quickly after seeing things on social media. It can spark a mob mentality,” Delgado said.

Delgado also said that in the last few years, he’s noticed a change in how his two children, ages 17 and 18, view race relations and politics.

“They are more into politics. Before, when I watched the news or ‘The Daily Show,’ they asked me to change the channel. Now we watch it together and they ask me to record those shows,” he said.

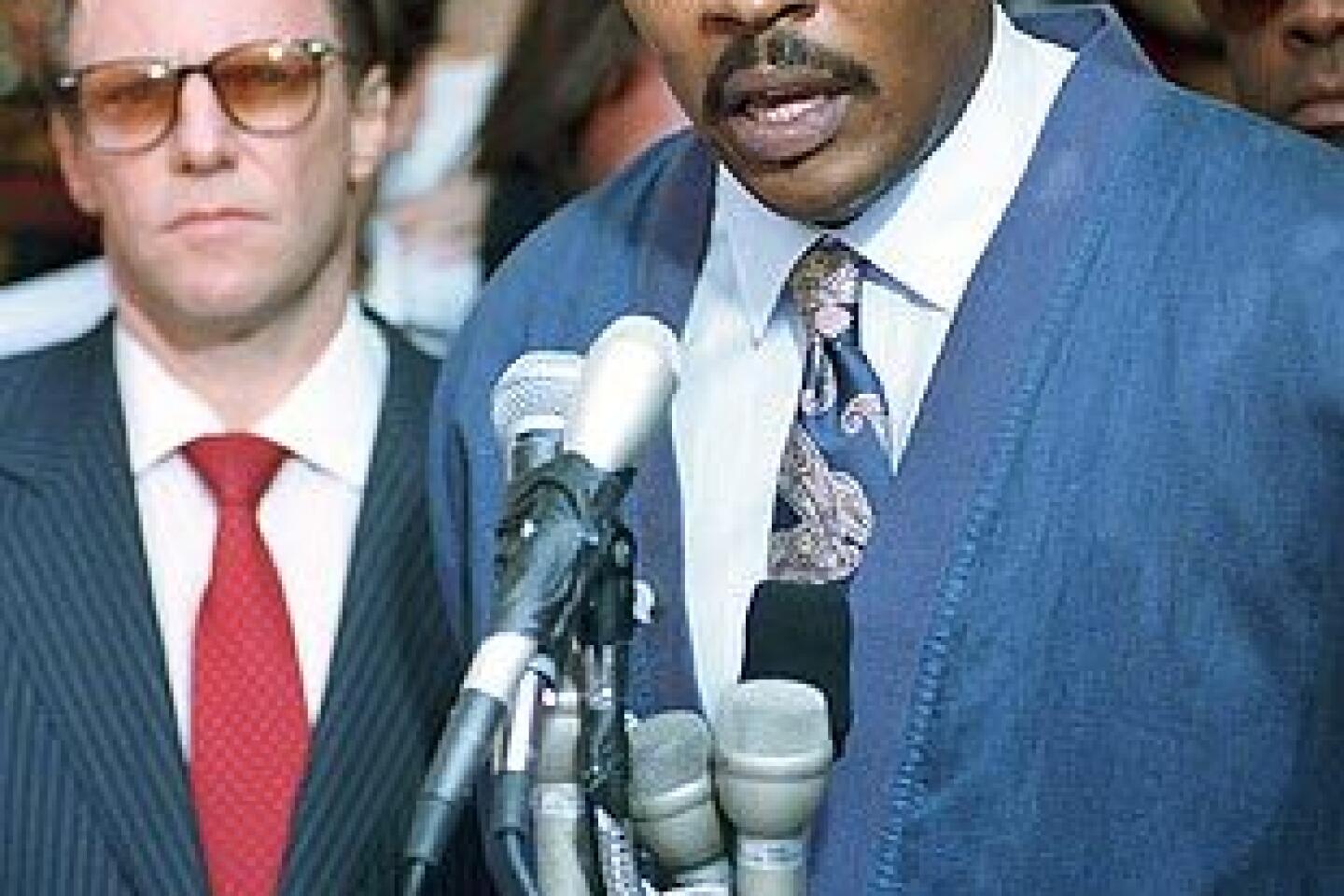

Brianne Gilbert, one of the researchers behind the survey, said the ubiquity of smartphone videos and social media may have made it so that there are many more moments like the videotaped beating of Rodney King.

“That kind of inflection point, that trigger point, those times are coming up sooner, more and more frequently than we’ve seen in the past,” she said. “We’re able to see things on more of an international scale, with social media and the Internet.”

Eighteen-year-old Jose Almanza, a freshman at the University of Southern California, said he sensed that agitation and interest among his friends. They all seem to want to go out to march, whether it’s for women’s rights or Black Lives Matter, he said.

“They blame something, they don’t know what it is exactly,” said Almanza, who grew up in Boyle Heights. “They can’t express it, so they just go out. A lot of people are doing it to be a part of something.”

Guerra, the political science professor, said the recent protest movements and election cycle may have shifted how people view a riot or uprising as a way to voice their discontent.

“Marching and protesting and, if necessary, rioting, is more likely today as a course of action. It almost seems more legitimate as a political strategy than ever before,” he said.

Some Angelenos said time had softened the edges that had led to the anger of 1992.

Tuesday afternoon, Javier Capetillo, 66, sitting on a chair in his East L.A. boxing academy, shook his head no and said in Spanish that he didn’t believe another riot like the ones that happened 25 years ago was possible. Capetillo and his son, Javier Capetillo Jr., lived in South L.A. when the riots broke out.

Capetillo said he remembered the years leading up to the L.A. riots, filled with crime, gang violence and police brutality. The riots, he said, allowed people to express their frustrations.

“People think things through nowadays, and there’s less crime. There was anger towards Hispanics, blacks and cops. But after the riots things got better,” Capetillo said.

Capetillo Jr., 41, a part-owner of his dad’s boxing academy, said he remembered what it was like to be a hot-headed youngster eager to take to the streets, having grown up amid gang violence and racial tensions in South L.A. When the riots broke out, as a 16-year-old, he didn’t think twice before grabbing cans of spray paint and heading to Long Beach with friends to wreak havoc.

“I was angry. I got beat up by a police officer in an alley one time and this was instant gratification,” he said. “But later on I met my mentor who turned out to be a cop. He got me my first job.”

ALSO

A judge has refused effort to block spending on California’s bullet train

Coulter says she’ll speak at UC Berkeley on Thursday, invited or not

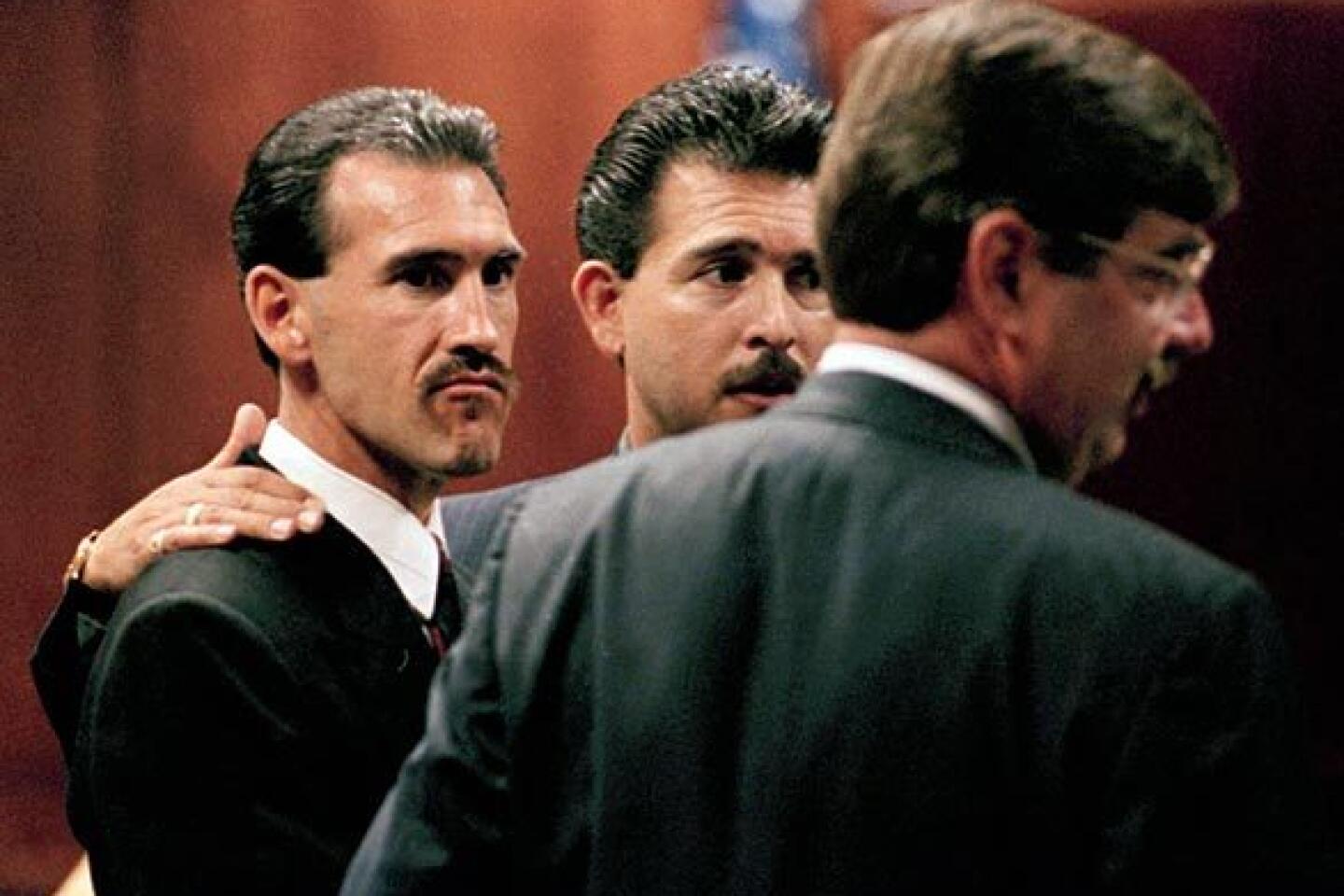

Another secret witness, three others to testify in Robert Durst’s murder case

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.