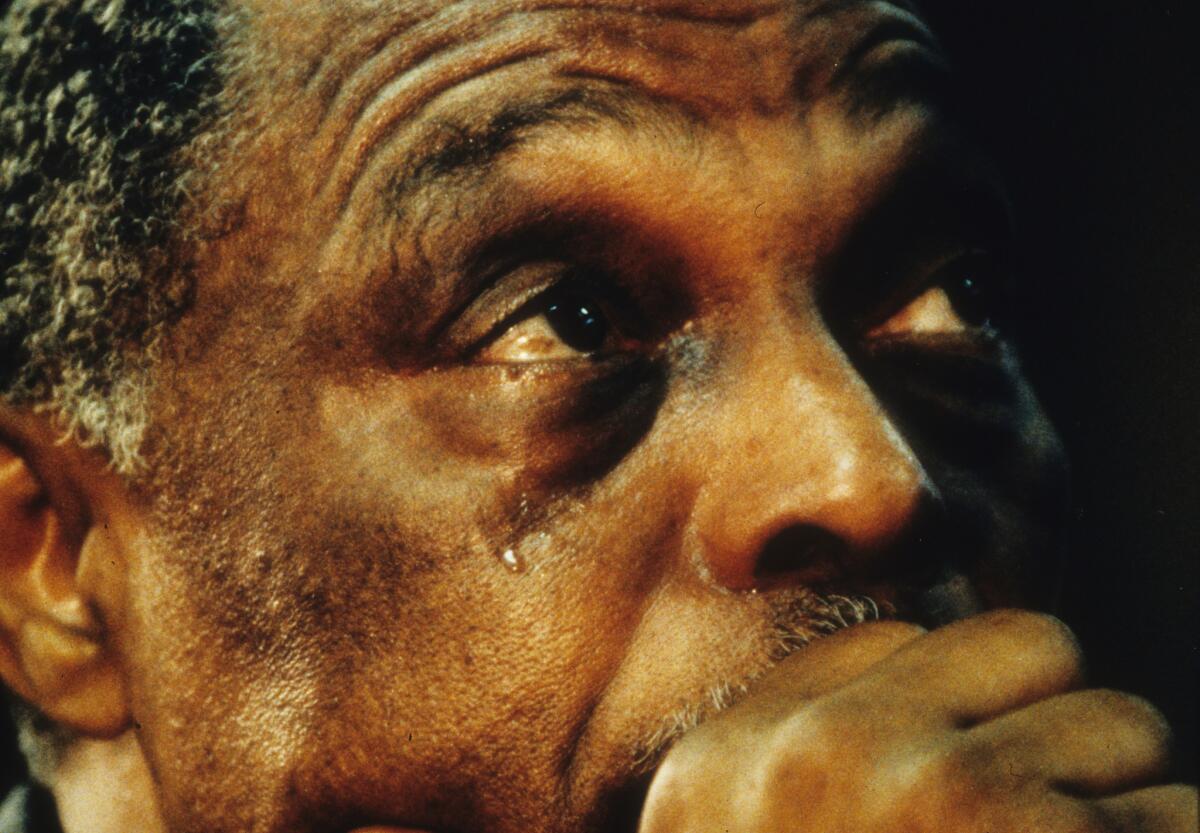

He tried to cool a city’s anger, only to watch helplessly as it burned during the 1992 riots

Rev. Cecil L. Murray and Rev. Mark E. Whitlock, Jr. of First AME Church in Los Angeles, recount the night of the verdict in the Rodney King beating trial and the hours that followed.

- Share via

Three days before the rioting began, the Rev. Cecil L. Murray took to the pulpit for his Sunday sermon.

“Be cool,” Murray implored. “Even in anger, be cool.”

For weeks, the 62-year-old pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church had watched anger and distrust grow in his community with each replaying of the video — the inescapable footage showing Los Angeles police officers cruelly beating Rodney King.

“And if you’re gonna burn something down, don’t burn down the house of the victims, brother! Burn down the Legislature! Burn down the courtroom!” he said.

His words were an appeal for calm, an effort to temper brewing frustrations as the jury deliberation was about to go into its fourth day.

He wiped the sweat off his brow. Behind him on the altar, a mural depicted the church’s illustrious history in the city. In front of him, above the pews filled with parishioners, were the the words, “First to Serve.”

“Burn it down by voting, brother! Burn it down by standing with us at Parker Center, brother! Burn it down by saying to [Police Chief] Daryl Gates: ‘This far, and no farther!’”

It was April 1992. Murray had led the city’s oldest and perhaps most politically active black church for almost 15 years. Back then, First AME played an outsize role in South Los Angeles, serving as a political and religious forum and a place for dialogue about issues facing the city — most notably the community’s rocky relations with the police department.

The oldest black congregation in L.A., First AME was the place national politicians went to reach black voters. It also was a social services organization that helped with housing, childhood education and low-income loans. The church — built in the Late Modern style by famed African American architect Paul R. Williams — sits on a bluff in the West Adams district, long a fashionable address for the city’s black residents, with commanding views of Los Angeles.

The King tape, with its grainy and harshly lit images, offered proof to the world of the brutal disregard the Los Angeles Police Department had for African Americans. The trial of Sgt. Stacey C. Koon and Officers Laurence M. Powell, Timothy E. Wind and Theodore J. Briseno had become a test of justice.

“The defense attorneys,” Murray continued, his voice rising in indignation, “are trying to convince us that we didn’t see what we thought we saw on that video. I don’t know what you saw, but I saw a man being brutalized! I saw an unarmed man being brutalized! I saw an unarmed, prostrate man being brutalized!”

But only a few believed that justice would be served, and Murray feared for the worst. Twenty-seven years earlier, six days of looting and arson had consumed the neighborhood of Watts. Thirty-four people had died.

The city, Murray believed, could not afford a replay of that violence.

“We had all thanked God for the video”

Three days later, Murray’s anxiety had not eased. Around lunchtime on April 29, word spread that the jury had reached a decision. An announcement would be made that afternoon.

The pastor knelt before the altar to pray. He asked God “to empower us to help liberty become ‘liberty and justice for all.’”

For weeks, Murray had been meeting with the mayor, Tom Bradley; the president of the Los Angeles Urban League, John Mack, and other city officials and community leaders to craft a plan for this moment.

They knew that with just a spark of violence and overreaction from the police, the city could ignite. They decided to hold a rally on the night the verdict was announced.

“If the verdict is just,” Murray explained at the time, “we must ask: ‘Where do we go from here?’ If the verdict is unjust, we must ask: ‘Where do we go from here, and how do we maintain stability?’”

Ushers placed speakers on the rooftop of the church to prepare for the large crowd, possibly overflowing into the street.

Mack, a respected voice for justice in the city and a fierce critic of the Police Department, rushed to the scene.

On several occasions during the three-month trial, he had driven from south L.A. to the courtroom in Simi Valley. He had studied the jurors’ faces as the prosecution played the tape.

They were motionless, he recalled. “They sat showing no emotion, no reaction one way or the other. They were stone-faced. I was hoping that the videotape was getting through, making the point that this beating was totally unwarranted.”

“We had all thanked God for the video,” recalled Mack, now 80 and retired, who had served after the riots as president of the Los Angeles Police Commission. Still, he wondered whether the jury would see what others had seen in the beating of King.

White Angelenos told him the video opened their eyes, and many condemned the officers’ actions. But the mostly white enclave of Simi Valley was home for many in law enforcement, and jurors — drawn from that community — might have supported the officers’ actions.

“Perhaps naively, we were still hoping against hope that this jury would find those officers guilty,” Mack said.

As he entered the church, he felt the urgency and fear, an “air of great expectation.”

Nearly 3,000 people had gathered in the sanctuary to watch the verdict on television. Together they heard what they had feared the most.

“Not guilty … not guilty … not guilty … not guilty.”

“We felt utterly helpless standing there”

Within an hour of the verdict, Los Angeles police were responding to reports of angry crowds on the streets of South L.A.

Police took positions near the corner of Florence and Normandie avenues, a few miles south of the First AME Church. But the crowd got so big the officers had to withdraw, leaving behind a growing mob.

More and more people — parishioners, strangers, television crews from around the world and community leaders like Mayor Bradley — arrived at the church, looking for answers.

Murray felt his adrenaline rise.

“We felt utterly helpless standing there,” he recalled a few days later. “Soon the palm branches and the fronds would catch; it would leap across the street. We would be consumed.”

Bradley stood at the pulpit and denounced the verdict, delivering a fiery speech broadcast on television.

“The jury’s verdict,” he said, “will never outlive the images of the savage beating seared forever into our minds and souls. … I understand full well that we must give voice to our great frustration. I know that we must express our profound outrage. But we must do so in ways that bring honor to ourselves and our communities.”

The reporters who were broadcasting live from the church had placed portable televisions along the pews, giving everyone a view of what was happening in the streets.

Everyone huddled to watch video feeds from circling news helicopters showing mobs attacking motorists. A white truck driver named Reginald Denny and a construction worker named Fidel Lopez were dragged from their vehicles and beaten.

Among those standing in the church was Kerman Maddox, a political science instructor at Southwest Community College and talk show host at a black-owned radio station. The manager was calling on him to report to the station and go live on the air.

“I think I need to be here,” he told his boss.

Outside, Maddox recalled, scores of people were banging on the doors, trying to get inside the church to take part in the services and pray. But it was already filled beyond capacity.

“Burning like Dante’s inferno”

Murray was sitting in the pews when an usher asked him to come outside.

First AME overlooks the Hollywood Hills, the skyline of downtown and a grid of boulevards typically bustling with traffic.

But that night, Murray saw “the fires of Hell” as the riots spread from the south, “burning like Dante’s inferno.” And, as he recalled, “they were all coming north.”

Murray went back in and told Bradley. The mayor went outside to see the destruction with his own eyes. He told the crowd that he had to return to his office.

The Rev. Mark Whitlock, head of security at the church, had several men walk Bradley to his car, which was surrounded by people throwing rocks. They ripped the side molding off the car, Whitlock recounted, as security shielded Bradley.

“That, for me, was an eye awakener,” he said.

If the mayor of Los Angeles, a respected African American leader, could be treated this way, then the city would burn.

‘Please, allow us to handle them’

Inside the church, the choir began to sing, an effort to calm those who had gathered. But Murray and Whitlock were not calm. Los Angeles was burning, and they needed to do something.

Together with 75 other men, many of whom were pastors dressed in their Sunday suits, they linked arms the night of April 29 and strode onto the main streets near the church, a “troop of peace and arbitration.”

They walked to the corner of Western Avenue and Adams Boulevard, where a landmark of South L.A. had been built: the 1949 Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, designed by Williams. At its groundbreaking, the Los Angeles Sentinel described it as “the finest building to be erected and owned by Negroes in the nation.”

By the time Murray and his team arrived, the building was in flames.

Murray called the fire department. Firefighters said they would come, but young men were attacking them, preventing them from doing their jobs.

Murray reassured them. He and the others would stand between the fire crews and the rioters who were throwing rocks.

As they took up positions, two men were hit. One had to be taken to the hospital.

The biggest challenge, Murray remembered, came when the police arrived. The officers wanted to charge the rioters.

“We asked: ‘Please, allow us to handle them,’” Murray recalled telling officers.

But the police continued to advance.

Murray ordered his crew to stand between the rock throwers and the officers, an action that helped defuse the standoff.

‘What happens to a dream deferred?’

Early the next morning, Murray and the men canvassed the neighborhood. The pastor recalls thinking about the famous poem by Langston Hughes.

“What happens to a dream deferred?” the poet asks of Harlem. “Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? … Or does it explode?”

Surveying the destruction, the fires and ash, the debris from the looting, Murray had his answer.

Twenty-five years later, Murray looks back on that night with pain and hope. He believes the riots finally forced reforms at the LAPD that have significantly improved relations with the black community.

“The police mentality was altered greatly,” he said. “That’s one of the positives that came out of that burning.”

He often wonders whether 1992 could have been prevented had LAPD Chief Gates and the department made changes earlier.

After the riots, First AME’s influence continued to grow. The church was a big part of the rebuilding effort, administering a variety of job and small-business programs.

Murray retired as pastor in 2004. He now teaches at USC’s Center of Religion and Civic Culture and heads a center for community engagement named after him.

“Even today … the tension is real,” said Murray, 87. “The police are our protectors and our defenders. But the question comes, who will protect us from our protectors? Who will defend us from our defenders?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.