Tommy Trojan, meet your female counterpart

Sculptor Christopher Slatoff gives us a look into his process of creating Hecuba, a queen of Troy in Greek mythology.

- Share via

Since the 1930s, the life-size bronze warrior Tommy Trojan has been the unofficial mascot of USC and a central campus gathering spot.

Now he has a female counterpart at USC Village — the $700-million complex of residential colleges, shops and restaurants just north of the main campus.

The new development is the university’s largest construction project, and USC President C.L. Max Nikias from the start saw a sculpture as its centerpiece.

Tommy Trojan, modeled after USC football players, flexes every muscle in his body at once. Nikias wanted the new statue to do something perhaps equally impossible: embody the breadth of campus diversity.

That’s what he told local sculptor Christopher Slatoff, whose work includes the new “Enduring Heroes” memorial to soldiers in Pasadena.

A devotee of classical antiquity, Nikias told Slatoff he was drawn to Hecuba, a queen of Troy in Greek mythology.

Hecuba, he said, was a model of resilience. She urged the Trojans to fight on “even when they were outnumbered, exhausted, facing impossible odds.”

Hecuba will be publicly unveiled Thursday.

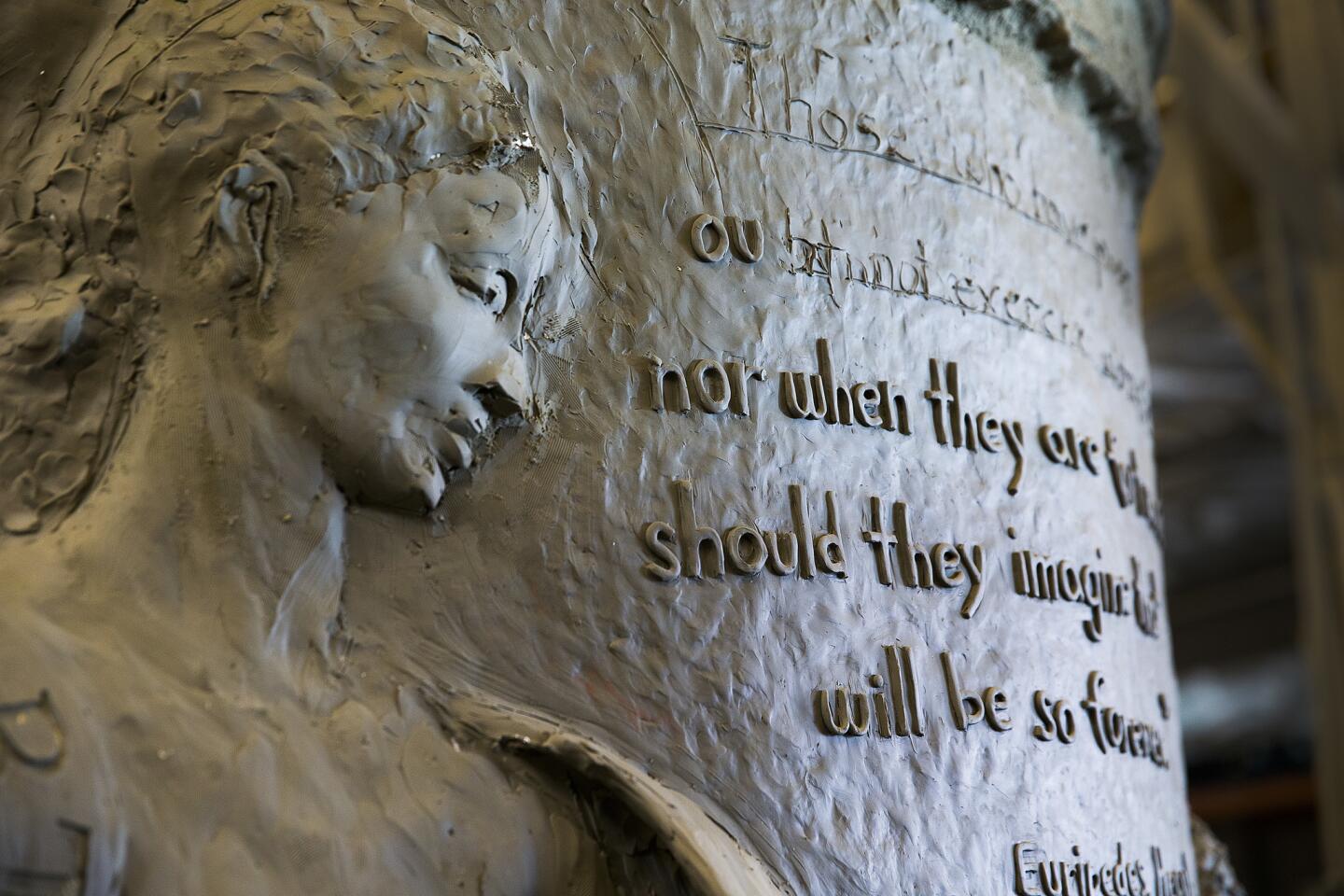

Slatoff began shaping Nikias’ vision of the Trojan queen in the winter of 2014.

Nailing down the concept

The sculptor pored over images, which he taped around his Lincoln Heights studio, and studied subtle differences in coloring and finish on ancient Greek bronzes at the Getty. He read from “The Iliad” and “The Aeneid.” He listened to lectures on Greek tragedy. He watched movies about Ancient Greece — and said he got goosebumps seeing Katherine Hepburn play Hecuba in “The Trojan Women.”

Meanwhile, Nikias sent a steady stream of suggestions. On a visit to the Acropolis in Athens, he admired the caryatids’ braids and texted photos to Slatoff, asking him to do something similar with Hecuba’s hair.

Hecuba was Priam’s wife, and the mother of Hector and Paris, familiar to many from “The Iliad.”

“In some accounts, she had as many as 19 children,” Slatoff said. “She had Hector, who was the warrior, a man of great character. She had Cassandra, who was the mystic, who had the gift of prophecy, and Paris, who was the politician.… It’s just this incredible range of concepts — and coincidentally, there are 19 schools at USC.”

On the cylindrical base of the 20-foot statue, Nikias wanted six women representing Hecuba’s daughters, modeled after women of Native American, Mayan, Mexican, Japanese, Chinese, African American, Middle Eastern and Caucasian descent, connected by an unfurling ribbon that read Arts, Humanities, Science, Technology, Medicine, and Social Sciences. Hecuba’s face would be a blending of ancestry.

“I very strongly used the lips of the African American model. Then those cheekbones are from particularly the model with Mayan ancestry,” Slatoff said. “It was just ... trying to bring all these ideas together.”

As for Hecuba’s pose, finding the right one took time. He played with the idea of raising one hand and fashioning her braids around a crown and laurel, like the rising sun in USC’s logo — but Nikias found it too reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty. He raised her hands skyward, holding a diploma, but then felt she looked too much like “the women who come out in the middle of a boxing match shouting ‘Round 3!’”

“I’m never going to compete with Tommy Trojan for that iconic feel.... It’s from an age where we easily put warrior into education. So many of the ideas that I originally came up with still had a tinge of that,” Slatoff said, flipping through early notes. “There’s a wonderful bowl, a vase, that has Hecuba and her husband crying. She’s putting the armor on Hector. So what I wanted to do was have her with the helmet extended out here, where if you stood underneath her, it would be like she’d be putting the armor on for you when you leave USC — your diploma as your armor. But in the end, look what I’m doing, I’m militarizing it. I’m taking the queen of Trojans, I’m taking the female character, and I’m making her, once again, merely the cheerleader.”

Slatoff asked each model who came to his studio to strike a pose both regal and humble. One afternoon in fall 2015, a model brought her left hand close to her heart and gently extended her right hand, palm open, as if to welcome a visitor.

“That’s it. That is Hecuba,” said Slatoff, who by now spoke of her as an old friend.

Preparing the mold

“If you want to check out a sculptor’s real skill, find out how they do their drapery,” Slatoff said one day in November 2016 as he worked on a clay rendering of Hecuba’s dress. Using a hoop wire tool, with his right hand he made firm but delicate strokes, while his left thumb pressed and smoothed out the curves.

For most of the year, Slatoff had been working on a final rendering in a foam material and clay, adjusting the detail and sculpting versions from a few inches to many feet high. He’d had numerous sleepless nights, particularly after visits from Nikias, which usually brought new ideas and changes.

At two stories high, particularly in an era of drones, the sculpture had to look proportional from all angles, Slatoff said as he climbed up the stairs to squint at his latest mock-up. Those standing on the second floor of a residence hall, he said, would stare Hecuba in the eye. Others would look down upon her.

“If you stand from below and look up, she would look like a Tyrannosaurus rex if the arm is not long enough, “ he said. “But seen from a higher angle, or from further away, one arm might look disproportionately long.”

He said he often thought about students, including his youngest son, who recently transferred to USC.

“I’m doing this for people who will live with it every day…. This is like, ‘X marks the spot.’ This is, ‘I will meet you at the Hecuba.’”

Casting into bronze

In January 2017, the clay rendering was trucked to a Northern California bronze foundry, where Slatoff hovered over his baby for months.

Using an ancient process known as the lost-wax technique, foundry workers cut the figure into pieces and covered them with a viscous rubber. They stiffened the rubber molds with layers of plaster and pulled them off the clay. Then they poured wax into the molds to create a wax sculpture, which Slatoff could shave and carve to sharpen his designs.

The wax replica was then dipped piece by piece into a slurry that hardened into a ceramic-like shell. When heated to 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit, the wax melted and molten bronze could be poured into the voids.

Once every piece had been cast, welders reassembled Hecuba like a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Walking around with a hand file, Slatoff polished and perfected.

“Now comes the fun part: the patina,” he said. He had spent months studying how to achieve the texture and tones Nikias wanted — heating the bronze with a torch and spraying on chemicals to change the surface composition. Scrub it with cupric nitrate for greenish tones, with ferric for a brownish red. In places, he polished to let the raw bronze show through.

In early April, Slatoff, son at his side, arrived at Nikias’ office with photos and a sample of the patina. He straightened his shoulders and held his breath.

“Christopher, you make it look so real!” Nikias said.

Bringing Hecuba home

On a Friday night in July, a fully assembled Hecuba was strapped onto a flatbed truck and driven 390 miles south. USC Village project director William Marsh, with the help of a structural engineer and a dozen others, figured out how to cradle the 3,600 pound sculpture onto large furniture dollies, push her across the plaza and slowly rock her upright with a forklift. They built scaffolding and a chain-rig system to hoist her up in the morning, when the president would decide exactly how she should be positioned.

It had been more than seven years since USC had first announced its project plans, three years since the groundbreaking. The campus had overcome early opposition from neighborhood activists — agreeing, among other things, to pay $20 million to support affordable housing in the area and $20 million for street upgrades. Now, the fountain was up and running, the 180 trees were planted, the residential halls were furnished, ready to house 2,500 students.

When Nikias arrived to see Hecuba — framed by a California coastal live oak, lined up with the new clock tower — he admired her greenish tint and the way it harmonized with the new buildings’ brick facades.

Hecuba looks so majestic, so regal — she’s beautiful, he told Slatoff. But could her arm perhaps be lowered a little so that it wasn’t covering her neck? And on her right hand, he said, the bracelets were not quite of the era. Those could be removed, Slatoff said. Nikias nodded.

He circled the sculpture, craning his neck, studying the patterns, the braids, the sunlight on the ribbon’s curves. He examined the three quotes etched onto the statue and checked that the English translations from Euripides’ “Hecuba” matched the ones he had chosen and handwritten in ancient Greek:

“Those who have power ought not exercise it wrongfully, nor when they are fortunate should they imagine that they will be so forever.”

A crewman hoisted Hecuba off the ground. Nikias directed her to be rotated about three inches to the right, beckoning toward the main campus.

Read more at Essential Education, our daily look at education in California and beyond »

Follow @RosannaXia for more higher education news

ALSO

‘Hamilton’ opening night in Hollywood: Stars, song and some tears

One of four defendants in 2014 beating death of USC grad student sentenced to life without parole

LAUSD’s costly 20-year construction project ends with opening of $160-million Maywood campus

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.