Raging wildfires bring death and destruction to California’s wine country

- Share via

Reporting from Napa, Calif. — Scott Lambert and his wife were sleeping in their home north of Napa on Sunday night when they awoke to the sound of a honking horn and shouts of “Get out!”

At the door he was greeted by wind and an eerie night sky washed in orange.

Lambert, 76, and his wife, Laura, grabbed a few things and fled, first to a friend’s winery and then to a Napa community church that was doubling as a Red Cross shelter.

Heavy smoke choked the air and bits of white ash from the Atlas Peak fire drifted earthward Monday morning as he fretted over the fate of the house his parents bought three decades ago.

“I think the outlook is bad,” said Lambert, who is retired from the oil industry and has a passion for English literature. “I had my library, thousands of carefully selected books. My grand piano. My music …”

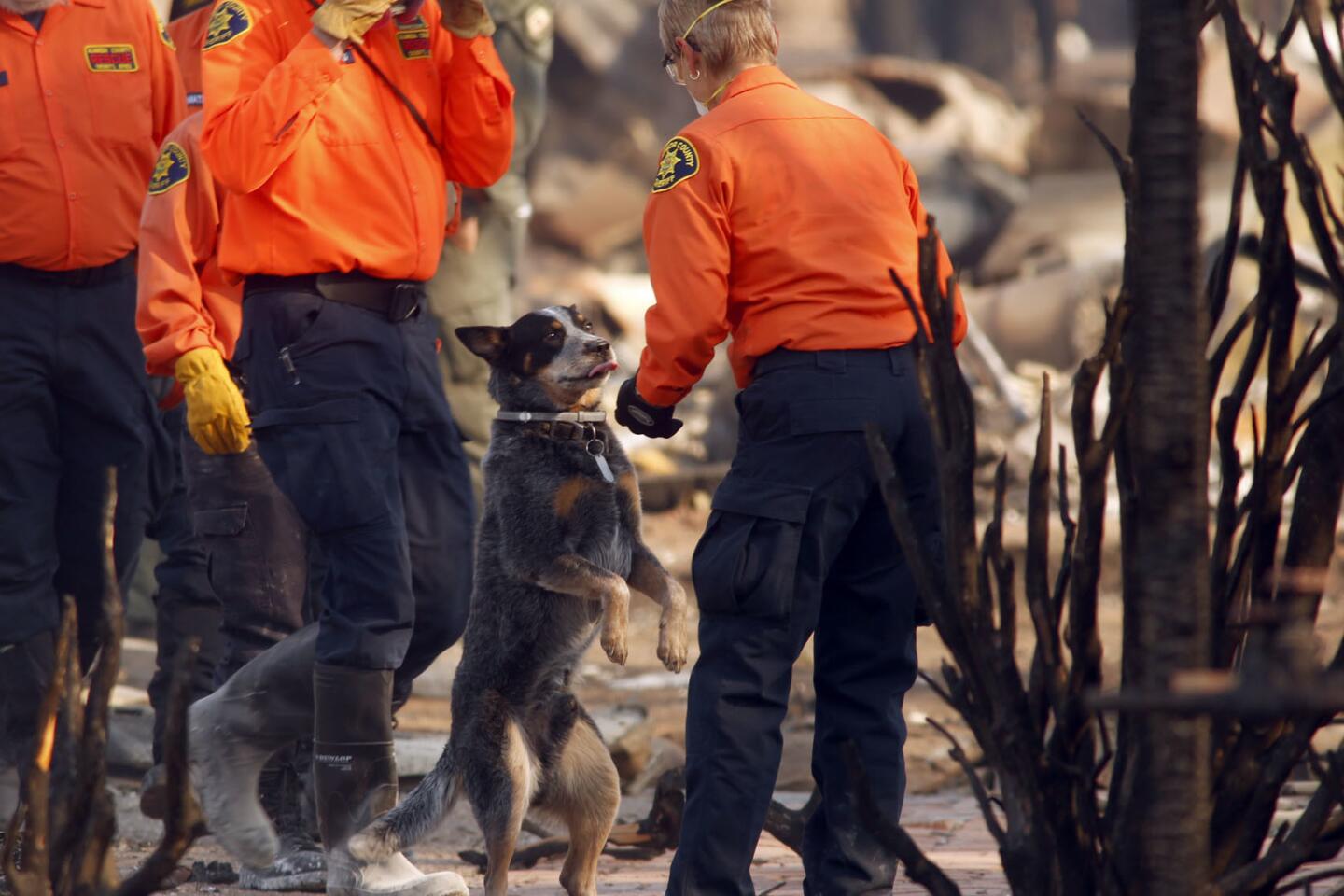

The Atlas was one of 14 wildfires that cut a devastating and deadly path across Northern California on Sunday night. Driven by appropriately named Diablo winds, the firestorm killed at least 10 people and destroyed 1,500 structures across eight counties.

Seven deaths were reported in Sonoma County, two in Napa County and one in Mendocino County, according to authorities.

As of Monday afternoon, the blazes ranked as the state’s fifth-most destructive and among the 10 deadliest.

“We are a resilient county,” Sonoma County Supervisor Shirlee Zane said. “We will come back from this. But right now we need to grieve.”

Officials with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection said 17 large wildfires, including the Anaheim Hills blaze in Southern California, had blackened more than 94,000 acres across the state. Three-quarters of the acreage was in the north.

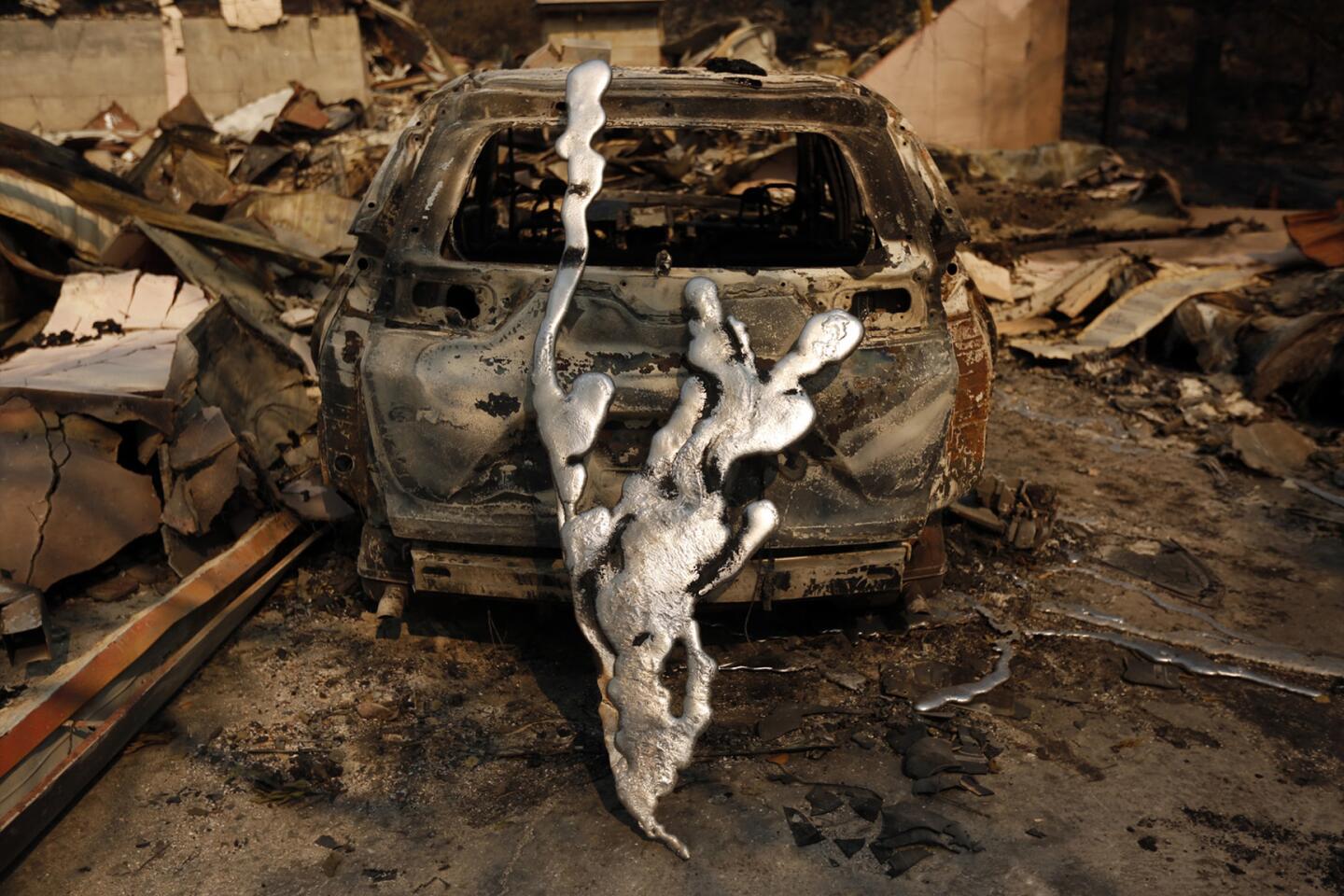

Leaping from ridge top to ridge top in grass and oak woodlands, flames raced across the heart of the California wine country, claiming houses, at least one winery and a dairy.

In Santa Rosa, the Tubbs fire leveled an entire neighborhood, burned a Hilton hotel, turned big-box stores into smoking ruins and prompted the evacuation of two hospitals, Sutter Santa Rosa Regional Hospital and Kaiser’s Santa Rosa Medical Center.

Santa Rosa is hit hard as fires swept through Sonoma and Napa counties.

Video on social media showed flames dancing in the background as nurses hurriedly wheeled a patient in a hospital bed across a parking lot, IV drip bags in tow.

“Late last night, starting around 10 o’clock, you had 50- to 60-mph winds that surfaced — really across the whole northern half of the state,” CalFire director Ken Pimlott said Monday. “Every spark is going to ignite.”

Though the conditions that fed the blazes — high winds from the interior, dried-up vegetation and low humidity — are more typical of Southern California’s fall fire season, the north has seen its share of horrific autumn wildfires.

The state’s second-deadliest blaze is the October 1991 Tunnel fire in the Oakland and Berkeley hills, which erupted on a quiet Sunday and killed 25 people.

The Tunnel also ranks as the most destructive wildfire in California history, consuming 2,900 structures.

Two years ago the Valley fire roared across Lake, Napa and Sonoma counties, killing four people and destroying 1,995 buildings.

The scene Sunday night when Brenda Burke, 55, fled her cottage north of Napa “was awful,” she said.

The fire “would move with the wind. You knew when a house went up because there would be a whole slew of smoke and you could hear the propane tanks exploding.”

Eager to find out if her home survived, she went back Monday morning, past fire-gutted houses and smoking lawns. When she got to her drive, she saw flames “from what appeared to be the front of my house.”

Later in the day she threw herself into volunteer work at an animal rescue organization.

Sitting outside a Napa emergency shelter with a dog and a cat pulled from a parked van, she managed a tight smile.

“I have what I’m wearing right now and my dog and my phone,” she said. “And I have friends and family. I will be fine.”

About 45,000 people were without power and/or cell service in Napa and Sonoma counties.

Residents flocked to Napa’s largely shuttered downtown to take advantage of the WiFi at a Starbucks, one of the few businesses open. The smoke was so thick that most drivers turned on their headlights.

In the hard-hit Coffey Park neighborhood of Santa Rosa, Diana Wilder stood outside the pile of rubble that was once her home, clutching a concrete Buddha lawn ornament.

“I wanted to take something from the house with me,” said Wilder, 53, a homemaker.

A safe and some flower pots were evident in the wreckage, but not much else.

“I was praying all night, ‘Please, house, still be there,’” said Wilder, who spent Sunday night with her husband in a supermarket parking lot.

Wilder returned to find every house on her cul-de-sac burned to the ground, the charred remains of washing machines, barbecues and chimneys standing amid the graveyard of homes.

She and her husband bought their house in 2000. Their monthly payment was $1,200. These days, she doubts she can find an apartment for that amount and plans to live with her brother until she figures out what to do next.

Houses usually burn when eaves or attic vents catch wind-driven embers. The embers may land on one building but not a neighboring house, often leaving a haphazard trail of destruction.

In one neighborhood, houses on one side of the street had barely a smudge on them. Across the street, there was little left but the scorched remnants of domestic life.

“There was no wind, then there would be a rush of wind and it would stop,” said Ken Moholt-Siebert, who fled with his wife, Melissa, as the Tubbs blaze bore down on his Santa Rosa vineyard.

“Then there would be another gust from a different direction. The flames wrapped around us,” he said.

At Jack London State Historic Park in Sonoma County, state park rangers packed irreplaceable artifacts Monday and began hosing down the roofs of historic buildings as the Nuns fire approached.

Rangers moved memorabilia, including London’s original typewriter and his wife Charmian’s Steinway piano, said Tjiska Van Wyk, the park’s executive director.

Several homes on London Ranch Road, which leads into the park, had burned to the ground.

It wasn’t just the Diablo winds — similar to Southern California’s Santa Ana winds — that turned Sunday into a nightmare of random destruction.

It was also the type of vegetation that was burning.

“Much of this is in grass-oak woodlands, which is why it’s spreading so quickly,” Pimlot said Monday.

Dried-out grass ignites easily and burns quickly, sending fires galloping across the landscape.

And despite a wet winter, Pimlot said vegetation still hasn’t recovered from California’s punishing drought. At the end of the summer dry season, all it needed was a spark and winds.

Conditions, he said, were “really explosive.”

To read this article in Spanish, click here.

St. John reported from Napa, Willon from Santa Rosa, Panzar and Boxall from Los Angeles. Times staff writers Makeda Easter, Sonali Kohli, Dakota Smith, Joy Resmovits, Rong-Gong Lin II and Geoffrey Mohan, in Los Angeles, contributed to this report.

Twitter: @paigestjohn

Twitter: @jpanzar

Twitter: @philwillon

Twitter: @boxall

ALSO

Fires strike a blow to the wine industry in Sonoma and Napa counties

Heavy smoke and ash from O.C. fire causes unhealthy air quality across region

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.