Claiming to be Cherokee, contractors with white ancestry got $300 million

- Share via

Reporting from St. Louis — Two years ago, when the mayor’s office in St. Louis announced a $311,000 contract to tear down an old shoe factory, it made a point of identifying the demolition company as minority owned.

That was welcome news. The Missouri city was still grappling with racial tensions from the 2014 fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old, in nearby Ferguson. After angry protests, elected officials had pledged to set aside more government work for minority-owned firms.

There was only one problem.

Bill Buell, the owner of Premier Demolition Inc., has no verifiable claim to being a member of a minority group. His ancestors are identified as white in census and other government records. And his claim to being a Native American rests on his membership in a self-described Cherokee group that is not recognized as a legitimate tribe.

The case highlights a major failure in the nation’s efforts to help disadvantaged Americans by steering municipal, state and federal contracts to qualified minority-owned companies. In many instances, government agencies have not vetted those companies to protect the interests of taxpayers and legitimate minority contractors.

Since 2000, the federal government and authorities in 18 states, including California, have awarded more than $300 million under minority contracting programs to companies whose owners made unsubstantiated claims of being Native American, a Los Angeles Times investigation found.

The minority-owned certifications and contract work were issued in every West Coast state, New Mexico and Idaho, Texas and four Southern states, several states in the Midwest and as far east as Pennsylvania, The Times found.

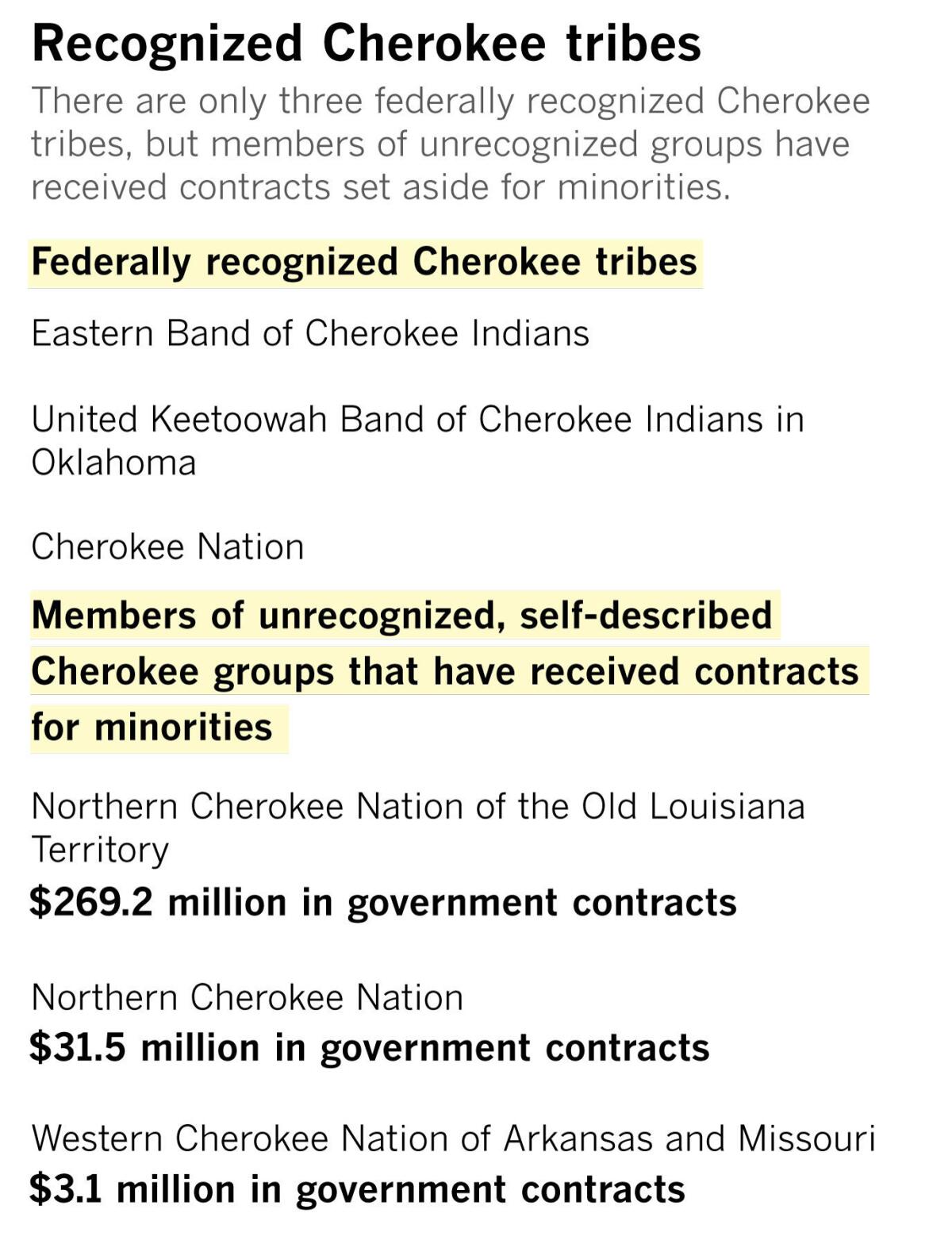

In applying for the minority programs, 12 of the 14 business owners involved claimed membership in one of three self-described Cherokee groups, according to government records and interviews.

Those three groups have no government recognition and are considered illegitimate by recognized tribes and Native American experts, however.

The three groups are the Northern Cherokee Nation, based in Clinton, Mo.; the Western Cherokee Nation of Arkansas and Missouri, based in Mansfield, Mo.; and the Northern Cherokee Nation of the Old Louisiana Territory, based in Columbia, Mo.

The applications for the other two of the 14 owners were not available. Their businesses were identified as Native American-owned in a Small Business Administration database and in federal contracting records.

For each of the 14 companies, one or more census, birth, marriage or other government records identified the owners’ ancestors as white. The ancestors also do not appear on rolls that government-recognized tribes use to confirm Cherokee citizenship, according to census records and an expert on Cherokee genealogy.

In response to questions from The Times, the governing body that oversees minority contracting certifications for St. Louis held a hearing on June 6 and moved to strip five contractors — including Buell’s demolition company — of their minority status.

Matt Ghio, an attorney who represents four of the five companies, including Buell’s, argued that the city rule defining a Native American as a member of a federally recognized tribe was unconstitutional. He said it set a “stringent” standard that other minority groups don’t face when seeking certification under the minority business enterprise program. He vowed to sue the city.

Ghio also said his clients could prove their Cherokee heritage, but would not do so at the hearing because the rules did not require it. The city of St. Louis subsequently said it reached an agreement with Ghio to put the decertification of the four companies on hold pending the filing of the lawsuit.

The total awarded to questionable Native American contractors is almost certainly significantly higher than $300 million.

But the Small Business Administration, or SBA, which issues minority certifications for federal contracts, discards records six years after companies graduate out of its program. Some state and local agencies also frequently destroy records or refuse to release them.

Others, such as the Kansas Department of Transportation, don’t require proof of tribal enrollment, only a signed affidavit swearing that one is Native American.

Under federal regulations, minority contracts are reserved for companies whose owners can demonstrate social and economic disadvantages because of their race or ethnicity. Among the eligible groups are Native Americans.

Each year, the federal government awards several billion dollars in contracts to Native American-owned companies in the SBA’s minority contracting program, often without competitive bidding.

State and local agencies award additional contracts under separate affirmative action programs, using criteria similar to the SBA’s to determine who is Native American.

But the vetting process for Native American applicants appears weak in many cases, government records show, and officials often accept flimsy documentation or unverified claims of discrimination based on ethnicity. The process is often opaque, with little independent oversight.

The contractors are concentrated in the Midwest and none could substantiate claims to Cherokee heritage, according to the Times review of census and other data. The Times worked with the Cherokee Heritage Center in Park Hill, Okla., which is part of the nonprofit Cherokee National Historical Society.

“It’s infuriating,” said Rocky Miller, a state lawmaker in Missouri and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, the largest of the three federally recognized Cherokee tribes. “They’re enriching themselves based on a nonexistent recognition.”

“It’s taking those resources not just from our community, but from all communities of color,” said Rebecca Nagle, a community organizer and citizen of the Cherokee Nation. “It’s really problematic.”

Twila Barnes, a Missouri-based researcher and a Cherokee Nation citizen who has written extensively about false claims to Cherokee heritage, said it’s wrong for people to get minority contractor status based on membership in unrecognized groups. “They are milking the system,” she said.

They are milking the system.

— Twila Barnes, a citizen of the federally recognized Cherokee Nation, about some contractors

Some of the cases involved tens of millions of dollars, according to a Times analysis of federal contracting databases and other government records.

A Texas company, AFCO Technologies Inc., received about $90 million in federal contracts earmarked for Native Americans or other minorities. The owner claimed membership in one of the unrecognized Cherokee groups and available census and birth records identify his ancestors as white.

A Missouri company, American Legacy Construction Group Inc., got more than $19 million in such contracts — including for work at a federally-run college in Kansas for Native Americans. The owner also claimed membership in one of the unrecognized Cherokee groups and his ancestors are identified as white in available government records.

The SBA continued to approve members of the Northern Cherokee Nation, or NCN, as minority contractors even though another federal agency, the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, has barred the group since at least 2003 from selling their wares as Native American-made because it is not a recognized tribe.

It is a federal crime to sell arts and crafts falsely labeled as Native American.

In a written response to questions from The Times, the SBA said that it did not violate its rules in certifying the contractors for the minority program.

The agency said it “certified businesses as eligible based upon the information provided to it and the regulations in place at the time of the eligibility determinations,” which was before 2011.

Contractors seeking minority status as Native Americans prior to 2011 had to have “held himself or herself out” as Native American and be recognized by others as a member of a Native American community, according to federal regulations at the time.

Federal regulations were simplified in 2011 and 2014 to limit the set-aside contracts primarily to members of state or federally recognized tribes.

But even after the regulation change, companies owned by members of the unrecognized Cherokee groups were awarded set-aside contracts through at least 2018, federal contracting records show. The SBA said this was because previously approved companies were grandfathered into the program.

The SBA did not specifically address The Times’ findings that the contractors’ ancestors were identified as white in government records available for review. The agency said it “takes allegations of fraud very seriously and routinely refers such matters” to its inspector general.

Cherokee genealogists and other experts say spurious claims to be Native American are common. They typically are based on family stories of tribal ancestry.

But some claims become politically charged. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who is running for president, long asserted Cherokee ancestry based on family lore, for example. Although she never claimed tribal citizenship, she identified herself as “American Indian” or minority on several documents before she entered politics.

After President Trump mocked her with the nickname Pocahontas, Warren had her DNA tested in October and the results showed she had a Native American ancestor six to 10 generations ago. She subsequently apologized for claiming to be Native American.

Last year, a Times investigation found that a company owned by in-laws of House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) won more than $7 million in federal contracts because of his brother-in-law’s membership in the NCN, one of the three unrecognized groups.

Most of the work awarded to the company, Vortex Construction, was for military projects in and around McCarthy’s district, including projects he supported in Congress.

McCarthy and the brother-in-law, William Wages, said they did nothing wrong. Wages, whose sister is married to McCarthy, said he is one-eighth Cherokee. Census and birth records available to The Times dating to 1850 show no Cherokees among his ancestors.

After the Times story was published, the SBA asked its inspector general to investigate how and why Vortex qualified for the contracts. A spokesman for the inspector general declined to comment on the investigation.

The Times’ reporting also triggered reviews by the California Department of Transportation and state authorities in Missouri. Vortex did not reapply for its Caltrans minority certification last August.

Caltrans examined the minority certification of Octane Concrete Pumping LLC, based in Paso Robles, Calif., because of owner Brad Dunn’s membership in the Western Cherokee Nation of Arkansas and Missouri, one of the groups that is not a federally recognized tribe.

Dunn got his minority certification last year through Caltrans. The state agency said Octane Concrete did not receive any contracts.

Dunn’s name and the date appear in handwriting on the tribal ID card that he submitted to Caltrans.

In a telephone interview, Dunn said his grandmother lives on a Cherokee reservation in Oklahoma. The state has no Cherokee reservations, although the Cherokee Nation has authority in some areas. Asked if the mother and father named on his birth certificate were his parents, Dunn said “nope” and hung up.

In response to The Times’ reporting, a Caltrans spokesman said, the agency removed Octane’s minority certification in April because Dunn did not respond within the required 30 days to a request “for information to verify his affiliation with a federally recognized tribe.”

Also as a result of The Times’ reporting, Miller, the Missouri state legislator, has asked the state attorney general’s office to investigate the recognition claims of the NCN, which has registered as a tax-exempt nonprofit. A spokesman for the attorney general’s office said the complaint was under review.

The NCN has claimed on its website and membership cards that it is recognized by Missouri as a Native American tribe, citing a state bill, proclamations it received from two governors and resolutions from the Legislature.

But the bill died in the state Senate and the proclamations and resolutions did not confer official recognition or have the force of law, according to spokespersons for the Missouri attorney general and secretary of state.

In telephone interviews, Kenn “Grey Elk” Descombes, the chief of the NCN, said federally recognized Cherokee tribes have unfairly denounced his organization because they don’t want competition for federal funds.

Descombes said the group has a secret Cherokee ancestry roll that is kept in a bank vault. He declined to show it to The Times, saying: “We would never let anyone get their hands on it. … It’s not for white people.”

Asked whether NCN members should benefit from minority contracting programs, Descombes said they should, and he then called African American contractors “professional liars and thieves.”

Descombes has long promoted the potential rewards of minority contracts for NCN members. The group’s website says it is recognized by a Missouri diversity program for “members wishing to become minority contractors.”

In Texas, San Antonio-based AFCO Technologies obtained its $90 million in federal minority contracts between 2000 and 2012. They included a $35.8-million contract in 2001 by the Air Force to construct pipelines in the San Antonio area.

SBA records state that AFCO is Native American-owned and Ronnie Earl Green is its president. The firm is also listed as Native American-owned in the federal contracting database, which is separate from the SBA.

Green is identified as a member of the Northern Cherokee Nation of the Old Louisiana Territory, the third self-described Cherokee group that is not recognized as a tribe, in a book that its chief wrote as a history of the organization.

Green’s ancestors do not appear in membership rolls of the recognized Cherokee tribes, according to Gene Norris, the lead genealogist for the Cherokee Heritage Center. Norris assisted The Times with researching the contractors’ claims to be Cherokee due to membership in one of the three unrecognized groups.

“They have no basis in representing themselves as Cherokee through their organization,” Norris wrote in a memo summarizing his research.

The Times tried to reach Green through phone calls, emails, letters and queries with his relatives and with attorneys who have represented him, but he did not respond. His company filed for bankruptcy in 2012 and appears to be inactive.

St. Louis has certified about 550 minority businesses, mostly owned by African Americans, according to city records. Of the 12 companies owned by Native Americans, the database shows, five were certified through NCN membership.

Kansas City certified three other contractors who claimed membership in the NCN or the Western Cherokee Nation of Arkansas and Missouri.

In response to an inquiry by The Times, a Kansas City spokesman said the municipality had reviewed the certifications and found no reason to revoke them.

Randal McKinnis, owner of American Legacy Construction Group, based in Lee’s Summit, Mo., has won $19.3 million in Kansas City and federal contracts since 2009, according to Kansas City and federal contracting records. His NCN membership card states he is 1/16th Cherokee.

In an email to The Times, McKinnis said his great-great-grandfather was listed on a 19th century Cherokee census. The person on the Cherokee census had the same name as McKinnis’ ancestor, but census records show McKinnis is not related to him.

Asked about the discrepancy, McKinnis said a cousin gave him “bad information” about his great-great-grandfather, but he said an uncle’s DNA test proved the family was Native American. He declined to provide the result to The Times.

In his 2008 application to the SBA, McKinnis wrote that larger contractors denied him the opportunity to bid on a job because they discriminated against Native Americans.

In an interview, however, he said his only memories of suffering racial prejudice involved other NCN members belittling his small percentage of Native American blood.

“I think everybody’s discriminated against to some extent,” McKinnis said.

I think everybody’s discriminated against to some extent.

— Randal McKinnis, owner of American Legacy Construction Group

One of American Legacy’s contracts was for carpet and seating work at Haskell Indian Nations University, the tribal college in Lawrence, Kan., that is run by the federal Bureau of Indian Education. Haskell did not respond to interview requests.

Global Environmental Inc., based in Berkeley, Mo., got $4.1 million in minority construction contracts from the federal government, and nearly $80,000 from St. Louis, federal and city records show.

In her application, owner Vicki Dunn, a member of the NCN, described the discrimination she had faced. Such narratives are part of the certification process.

Dunn said the vice president of a company that once employed her told her she did not understand the true meaning of the CEO acronym.

“Then he stated, ‘Me Chief, you Indian,’” Dunn wrote.

Dunn’s ancestors are identified as white in census and death records reviewed by The Times. The Cherokee Heritage Center genealogist said his research found no Cherokee ancestry for Dunn, who did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Vicki Dunn and Brad Dunn, owner of Octane Concrete Pumping LLC, did not respond to emails asking if they were related.

An Idaho firm, Purgatory Fence Company LLC, obtained $3.1 million in contracts for work on federal projects, contracting records show. The SBA-certified minority contractor was grandfathered into the program.

SBA records show that the owner, Neva Gardner, is a member of the Western Cherokee group, one of the three federally unrecognized groups.

Contacted by The Times, Gardner refused to talk about the Western Cherokee organization or her family heritage. In an email to The Times, an attorney for Gardner said his client is Native American by virtue of her membership in the Western Cherokee group. The attorney said Gardner’s mother is also Native American.

Murl Pierson, who identified himself as a Western Cherokee spokesman, said members relied on notes ancestors wrote in old Bibles and stories told by elders to verify their heritage.

The saga of Columbia Curb & Gutter Co. highlights the phenomenon of business owners getting minority contracts based on unsubstantiated claims of being Native American.

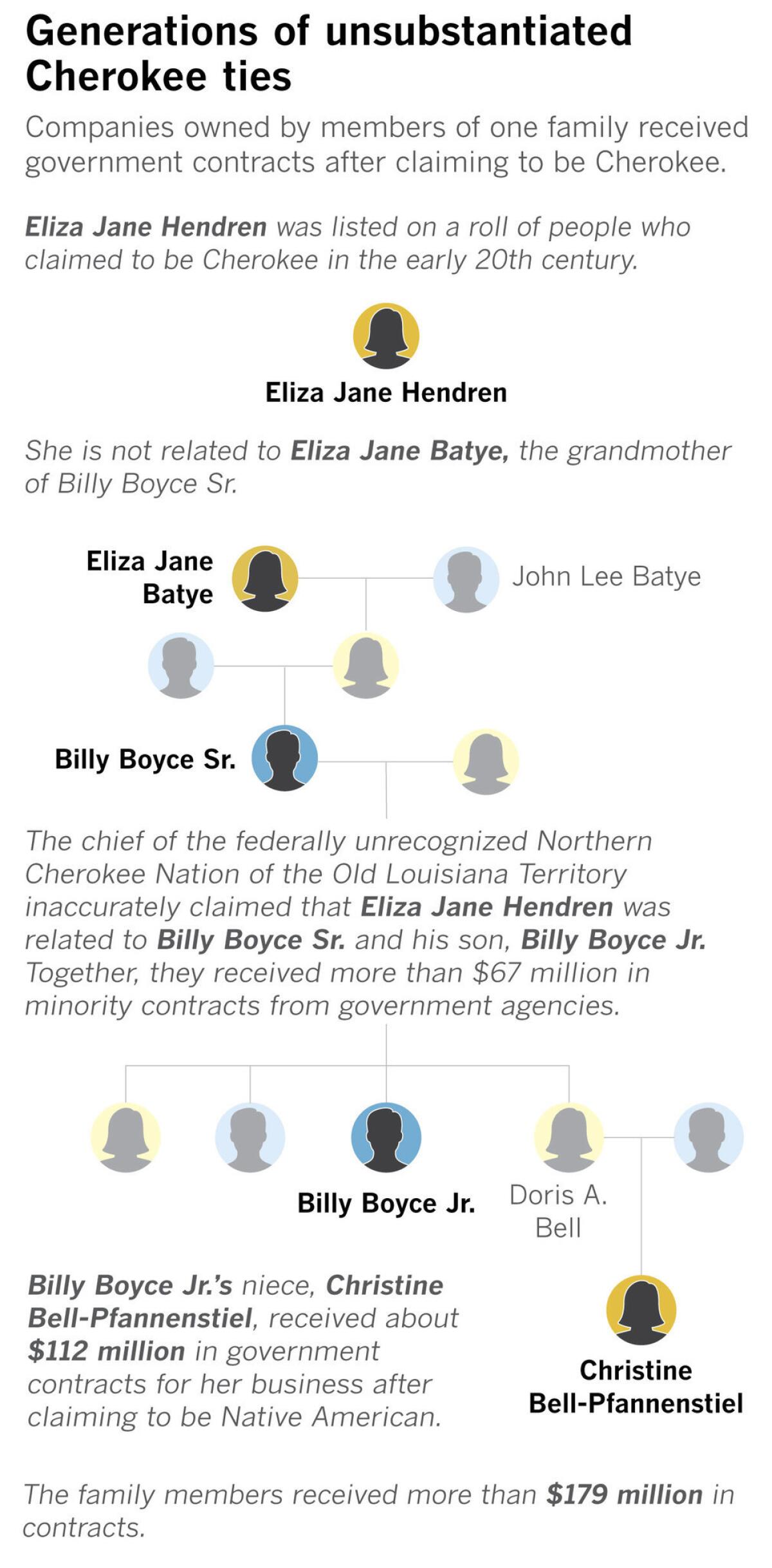

In 2000, Billy Boyce Sr. and his son set out to convince the Missouri Department of Transportation that their membership in the Northern Cherokee Nation of the Old Louisiana Territory group qualified them as minority contractors.

The state had sought to overturn the Boyces’ certification because the Northern Cherokee group was not federally recognized.

They appealed and were granted a hearing in Jefferson City, the state capital.

Beverly Baker Northup, chief of the group, testified that the elder Boyce’s grandmother was listed on the Guion Miller Roll, an old list of people who claimed to be Cherokee. That helped qualify the Boyces for membership in the group, Northup said, according to a transcript of the hearing.

But the woman identified on Guion Miller was not Boyce’s grandmother or even related to him, according to a Times review of application records on file with the roll, which is in the National Archives.

The document, compiled in the early 20th century, contains ancestry information on people who applied for government funds disbursed to Cherokees. Many were rejected for lack of proof that they descended from Cherokee citizens.

Northup’s own ancestors were turned down. None of her forebears is identified as Native American in census and birth records reviewed by The Times.

Her former husband, Robert Northup, then a deputy principal chief for the Northern Cherokee group, testified that one of the Boyces — he didn’t say who — had employed his “Indian-ness ability” to locate 100 gravesites of Native Americans at a rural cemetery in Boone County, Mo. A faded sign nailed to a post amid the weed-choked tombstones still labels it a Northern Cherokee burial ground.

Missouri officials seemed ill-prepared to challenge the testimony. The state attorney said he was unaware of the Dawes Roll, the document used to confirm Cherokee citizenship, and relied on Beverly Northup’s explanation.

The Boyces also got a major boost from the SBA, which had earlier granted minority status to Columbia Curb under its affirmative action program. The Boyces made a case to the SBA that they suffered economic hardships in general and, separately, social disadvantages as Native Americans, according to the attorney who represented them, Diana Carter.

The SBA dismissed pleas by Missouri officials to investigate the Boyces’ claim of being Cherokee.

“It was very frustrating,” recalled Sharon Taegel, who was a civil rights administrator with the state Transportation Department at the time. “The SBA … they didn’t like to be questioned.”

The Boyces prevailed and Columbia Curb ultimately received more than $67 million in minority contracts from the federal government, Missouri and other states.

Shortly after the hearing, Dan Akin, a former deputy principal chief of the Northern Cherokee, resigned from the group and disavowed its claims of legitimacy. He said his own ancestors are primarily Scottish and Irish.

While still in the group, Akin said in an interview, he had helped Northup write the history of the Northern Cherokee Nation of the Old Louisiana Territory.

It presents a theory that some members might have descended from survivors of the 1st Century Roman massacre of Jews in the siege of Masada in what is now Israel. In this tale, they escaped the slaughter and eventually drifted in boats across the Atlantic.

Northup “just made that stuff up,” Akin said.

In response, Northup said in an email that Akin “did not help write my book and it is not full of lies.”

Boyce died in 2011. His son, Billy Boyce Jr., now runs the company from a two-story industrial building in Columbia.

Boyce Jr. declined to be interviewed when a Times reporter visited the office. A framed 2007 newspaper article on the wall lists the Boyces as one of 10 “power families” in local business circles. As of this week, the company was still enrolled in the state program for disadvantaged minority contractors.

Boyce Jr. said he was a “tribal citizen” and referred all questions to Descombes, the NCN chief.

“I have nothing to say to you,” Boyce Jr. said. “Get off my property.”

A third generation of the family has gone into the minority-contracting business.

Columbia-based Bell Contracting Inc., owned by Billy Boyce’s granddaughter, Christine Bell-Pfannenstiel, has received about $112 million in federal contracts under the SBA program — bringing the total in minority contracts for the family to nearly $180 million, records show.

The SBA said its records documenting how Bell-Pfannenstiel qualified for the program were discarded after they became moldy because of a leak in a storage room ceiling.

Contract records identify her business as Native American-owned and the Northern Cherokee seal appears on the company’s website. She did not return phone calls and no one answered the door at her office and home.

Bell Contracting subsequently sent an unsigned email disputing The Times’ account. “My heritage is Native American and I do not need to prove that to you,” it said.

Times researcher Cary Schneider and staff writer Anthony Pesce contributed to this report.

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.