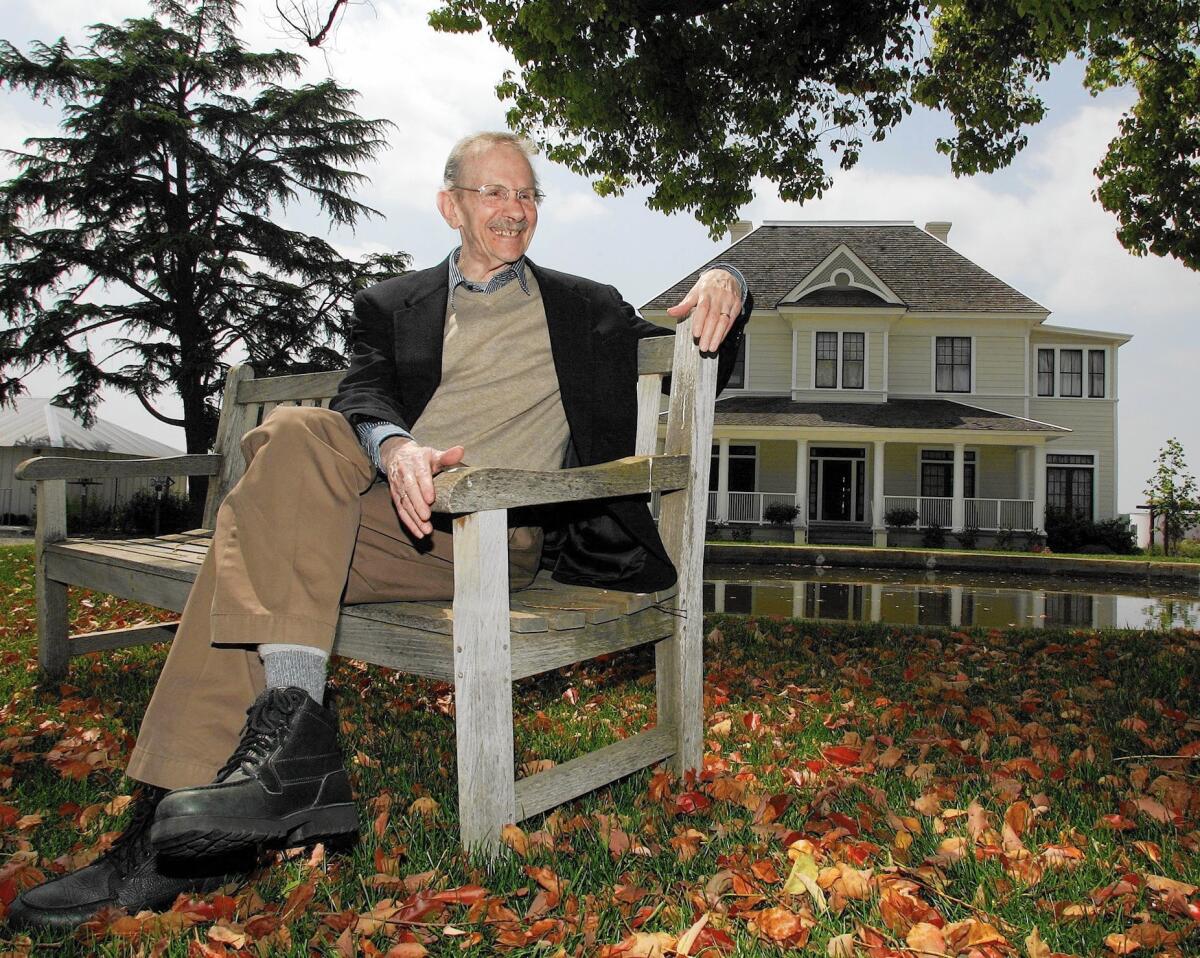

Philip Levine, former U.S. poet laureate, Pulitzer winner, dies at 87

- Share via

Philip Levine, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and former U.S. poet laureate who wrote elegies to American blue-collar workers sweating through despair-laced jobs, has died in Fresno. He was 87.

Levine, who was a professor emeritus at Cal State Fresno, died Saturday, said Timothy Skeen, a poet who coordinates the university’s master of fine arts program. The cause of death was pancreatic cancer, according to the Associated Press.

Levine filled more than 20 poetry collections with plainspoken images of the unforgiving industrial landscape he came to know in his native Detroit. He won the Pulitzer for his 1994 collection “The Simple Truth.” When he was named poet laureate in 2011, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington described him as “an extraordinary discovery because he introduced me to a whole new world I hadn’t connected to in poetry before.”

“He’s the laureate, if you like, of the industrial heartland,” Billington told the New York Times. “It’s a very, very American voice. I don’t know that in other countries you get poetry of that quality about the ordinary workingman.”

In “What Work Is,” one of Levine’s best-known volumes, he describes a swingshift for an ordinary worker mixing chemicals at Feinberg and Breslin’s First-Rate Plumbing and Plating:

Half an hour to dress, wide rubber boots,

gauntlets to the elbow, a plastic helmet

like a knight’s but with a little glass window

that kept steaming over, and a respirator

to save my smoke-stained lungs. I would descend

step by slow step into the dim world

of the pickling tank and there prepare

the new solutions from the great carboys

of acids lowered to me on ropes....

For some of the characters who inhabit his poems, love is as tough as work.

In “Belle Isle, 1949,” the young narrator and a girl whose name he doesn’t know go skinny-dipping in the Detroit River

to baptize ourselves in the brine

of car parts, dead fish, stolen bicycles, melted snow....

After splashing through the muck, they return

to the gray coarse beach we didn’t dare

fall on, the damp piles of clothes,

and dressing side by side in silence

to go back where we came from.

Levine aimed for meticulous honesty in his poems and those of his students. He taught in universities all over the U.S., including NYU, Brown, Columbia, Princeton, Vassar, Tufts and his alma mater, Wayne State in Detroit. From 1958 until his retirement in 1992, he was based at Cal State Fresno, where a culture of young Central Valley writers sprouted around him.

In “The Bread of Time,” a series of autobiographical essays, he said he was recruited after a one-year Stanford fellowship to Fresno by a dean with a face “unfurrowed by thought.”

The dean told Levine about the marvels of hiking in Yosemite. Levine did not tell the dean that “hiking was what we did in Detroit when the car broke down.”

Years later, he said that his Fresno students were the best he ever taught.

“You’d tell them they had two or three lines out of 20 lines that were genuine and authentic, and they didn’t have a problem with that,” he told the Fresno Bee in 2008.

His Ivy League students also differed from their less privileged counterparts in Detroit, wrote poet Michael Collier.

“Princeton students were apt to become emotionally undone when he critiqued their poems,” Collier noted, whereas Wayne State students were likely to unleash an obscenity in response.

Born in Detroit on Jan. 10, 1928, Levine was one of twin sons born to parents who were Russian Jewish immigrants. Levine’s father, Harry, sold used auto parts and his mother, Esther, sold books.

At 14, Levine picked up a part-time factory job — the first in a succession that included Chevy Gear and Axle, the Mavis Nu Icy Bottling Co. and Detroit Transmission. That last one was the worst, he told the Los Angeles Times in 1994, but, he added, it was better than the semester he taught at Princeton.

Encouraged by his high school teachers, he finally applied to Wayne University (it later became Wayne State). Thinking of his co-workers, he decided to become a writer and “find a voice for the voiceless,” he told Detroit magazine.

“In terms of the literature of the United States,” he said, “they weren’t being heard. And as young people will, I took this foolish vow that I would speak for them.”

For years, he expressed bafflement over poetry lacking people.

“There’s a lot of snow, a moose walks across the field, the trees darken, the sun begins to set and a window opens,” he told a Paris Review interviewer in 1988. “Maybe from a great distance you can see an old woman in a dark shawl carrying an unrecognizable bundle into the gathering gloom.”

When people do appear, he said, “their greatest terror is that they’ll become like their parents and maybe do something dreadful, like furnish the house in knotty pine.”

In 1957, Levine received a master’s of fine arts degree from the University of Iowa and went on to Stanford.

Over decades, he sunk his roots in Fresno but spent part of the year in Brooklyn.

Earning a living with poetry and appearances at writers conclaves, he could have lived anywhere in his retirement — but he had a fondness, he told The Times, for his Fresno doctor, his dentist and his mechanic. He also trained at a local gym with a former Mr. Universe.

“It took ages to find these people,” he said. “You don’t just run out on a great car mechanic.”

Levine’s survivors include his wife of 54 years, Frances J. Artley; sons Mark, John and Teddy; brothers Edward and Eli; five grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

[email protected]

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.