Urban legend about Times reporting during Watts riots conceals a sadder tale

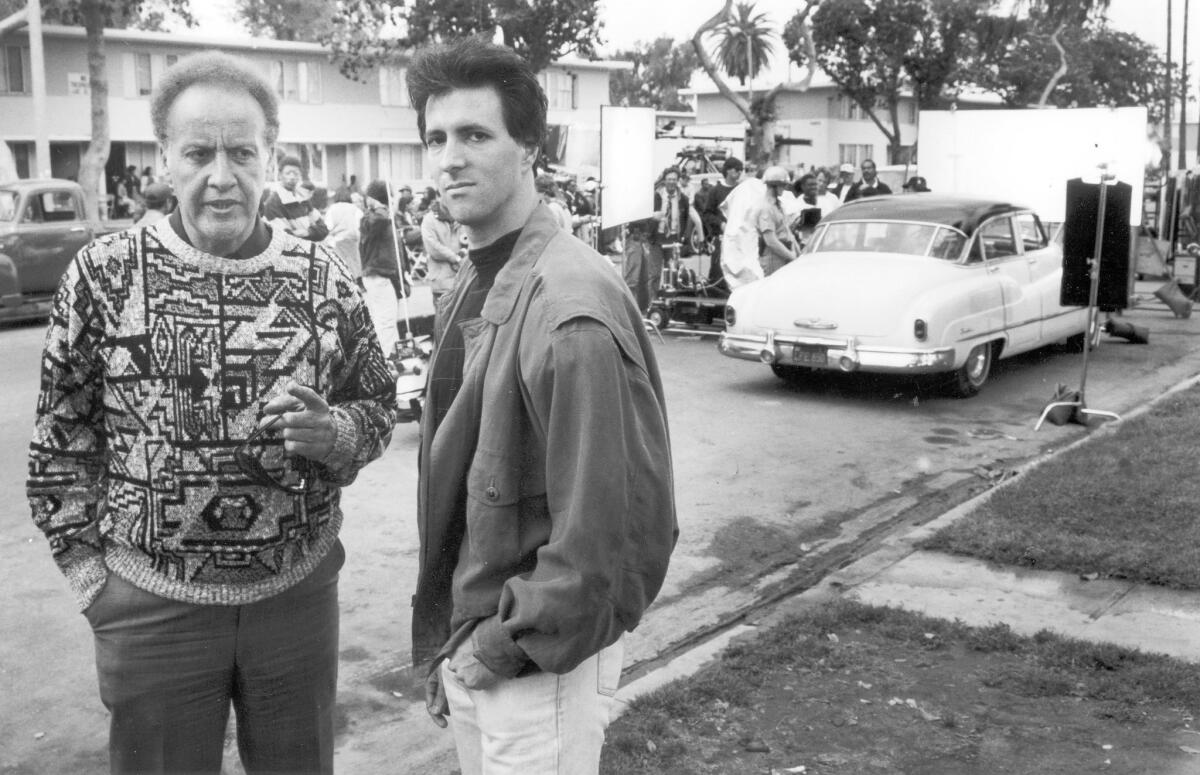

Bob Richardson, left, and Michael Lazarou in 1990 on the set of “Heat Wave,” a movie about the Watts riots.

- Share via

In August 1965, as violence flared in Los Angeles’ African American neighborhoods, Robert Richardson became a part of urban legend.

The story has been polished, embellished and transformed in street corner, newsroom and media retellings for 50 years.

Perhaps the most ingrained version features Richardson as an unsuspecting 24-year-old who timid Los Angeles Times editors abruptly plucked from the paper’s advertising department and sent marching into the danger zone to save the paper’s reputation when the entirely white reporting staff was too frightened to go.

The truth is more nuanced. And sadder.

Some of Richardson’s story was told in his Times obituary in 2000.

Richardson had moved from Birmingham, Ala., to Los Angeles as a young child with his parents and five siblings. They settled in South Los Angeles and Richardson, known as Bob, attended Fremont High School, about three miles from the intersection where the Watts riots began. He dropped out in 11th grade to become an Army sharpshooter, and joined The Times about a year before the riots as an advertising messenger.

According to his sister Yvonne Wynn, Richardson liked the idea of becoming a reporter. He often tuned into the police frequency on a transistor radio, Wynn said, a habit he continued until he died.

When rioting erupted in Watts, he wanted to tell people what he had seen.

The late Charles Hillinger, who was among the throng of Times reporters who covered the riots, recalled what happened in an email exchange after Richardson’s death. He said Richardson “came into the city room late on the second night right from the scene where all hell had broken out to tell us he was caught in the middle of the riot,” he said.

Editors welcomed him, the late Times reporter Eric Malnic said in another email. “He played a vital role — we had no blacks on staff at the time — and gave us a much-needed measure of credibility. He was bright, observant and hard-working.”

Richardson’s first-person stories, called in from phone booths and rewritten by editors as almost all stories were during such major news events, describe rioters pulling white people from their cars and beating them, looting stores and sending buildings up in flames. He watched his childhood supermarket turn to rubble, and one of his stories may have introduced the mantra, “Burn, baby, burn,” the slogan of radio DJ “Magnificent” Montague, to those outside Watts.

The Times also published an article by black radio reporter Larry Hall, who happened to be in town on vacation from New Jersey. But Richardson’s was the only voice of a black Times staffer.

In his earliest report, The Times called him “a Negro and an advertising salesman” — although he was actually a messenger.

A week later, the paper was referring to him as part of the “news staff.”

As the fires died down, Richardson tried to explain why his community had erupted in anger.

“Maybe part of the explanation lies in the fact that for so many Negroes who have come here believing Los Angeles to be a city of golden opportunity, the promise has become a myth,” he wrote.

When Watts cooled off, The Times kept him on as a reporter, assigning him the night shift to cover fires and other emergencies. Richardson called his assignment the “disaster desk.”

He dreaded being called to work and worried about the high expectations of his white bosses and his black neighbors, and he often wound up drinking with other reporters at the nearby Redwood Restaurant, which featured a red telephone connected directly to the newsroom. “I was incapable of doing anything in depth,” he said in one interview. “I was scared to death every night.”

Less than a year after his first byline, Richardson was arrested on a relatively minor charge — the most credible reporting says he stole an ashtray from a downtown hotel — and The Times asked him to resign in return for springing him from jail.

When The Times received the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the riots, Richardson didn’t show up at the ceremony, saying he didn’t think he deserved the recognition.

Soon, Richardson found himself on skid row, and he spent the next couple of decades floating among homes and jobs, including radio and TV assignments, as he battled alcoholism.

In 1987, Penelope McMillan, then a Times reporter, met a tall, light-skinned African American with red hair and freckles at a homeless encampment where he was working with the Salvation Army. Richardson told her his name, and eventually persuaded her that he too had once been a reporter. They established a rapport.

“I asked him why he didn’t quit, if the reporting job was such a disaster,” McMillan said in an email this week. “He said that at the same time he was screwing up, he was also getting a huge amount of attention from the black community, getting honored at this dinner and that, and reveled in it.

“All his life, he said, he’d been bullied and ostracized by other blacks, in his family and community because of his strange looks.... He didn’t want to give up all that attention.... Bob told me he was given no help, was instead thrown into a sink-or-swim situation, and he sank.” McMillan explained in an email this week. “Hence those nights in the Redwood staring at the red phone.”

“I guess we didn’t recognize it at the time, or didn’t want to, but he was really up against a very, very difficult situation,” said the late Art Berman, one of Richardson’s editors, in an interview with ABC’s “20/20” program in 1990.

When the 25th anniversary of the riots approached, Richardson called the late Times editor Jack Jones, one of the riot reporters, reminding him of the past. He found out that a 29-year-old screenwriter, Michael Lazarou, had been looking for him for two years, hoping to weave his story into a film about the riots.

“Heat Wave” aired in 1990 on the TNT cable network, depicting Richardson as a well-liked young man striving for a career, even as fellow blacks struggle to find construction jobs.

Lazarou said in a recent interview that Richardson’s voice in the paper was “as far away from The Times style sheet as you can get. These were the impressions of an African American man who lived in Watts, not some white guy.”

He called him “one of the most intriguing and confounding people I ever met,” with a tremendous sense of humor and a deep voice.

“Bob and irony were longtime companions. He was a master code switcher.… A voracious autodidact who could hang with and penetrate a gang set one minute and make a one-percenter feel equally open and at ease the next,” Lazarou said in an email. “I liked him a lot. I miss him.”

The film’s narrative ends just as Richardson becomes a Times reporter.

What followed, Richardson told a Times reporter in 1990, included typing, digging ditches, truck driving, insurance peddling, bounty hunting, dishwashing, selling tamales and being a disc jockey. There was also a three-month stint at the California Institution for Men at Chino for check forgery.

Richardson earned more than $50,000 in consulting fees for “Heat Wave” and that helped him get off the streets. With the first $12,000 check, he bought a car, his wife, Alice Richardson, recalled in an interview after his death from an asthma attack at the age of 59.

Ten years before his death, Richardson told “20/20” that he didn’t blame The Times for the way his career unraveled: “If I had been sober, if I had been standing straight, if I had been awake, you know, maybe things would have turned out different.”

Before Richardson moved into reporting, The Times had no African American reporters. Fifty years later, African Americans make up 3.4% of the staff across the newsroom, including designers, Web developers and a handful of reporters, according to the American Society of News Editors. Representation is better at some California news organizations, but most of the state’s publications that reported data had no African American reporters.

[email protected]; [email protected]

Twitter: @dainabethcita; @dexdigi

Full coverage of the Watts riots, 50 years later

Stunned by the Watts riots, the L.A. Times struggled to make sense of the violence

50 years after the riots, ‘There is still a crisis in the black community’

Latinos now dominate Watts, but some feel blacks still hold power

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.