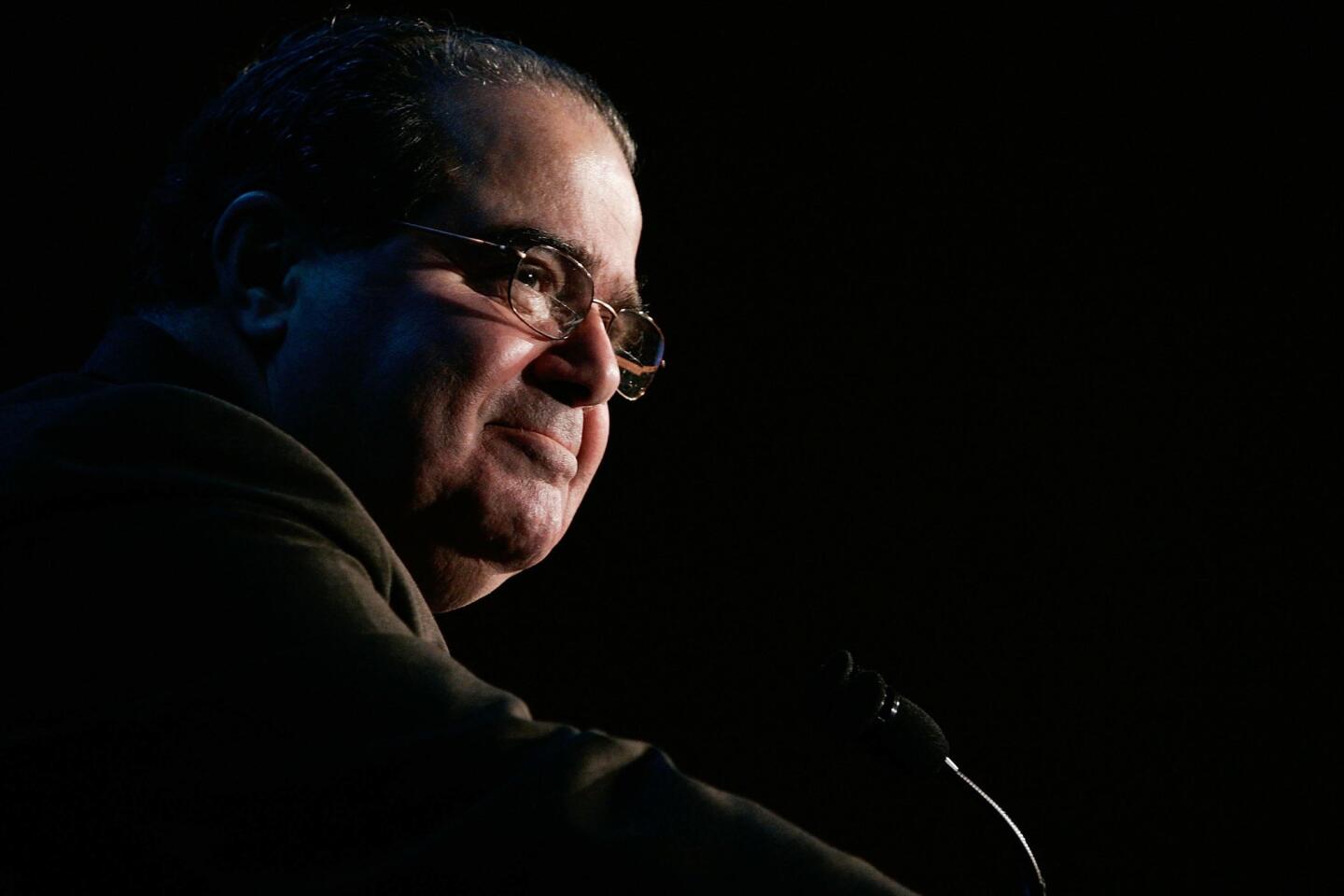

From the archives: BFFs Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia agree to disagree

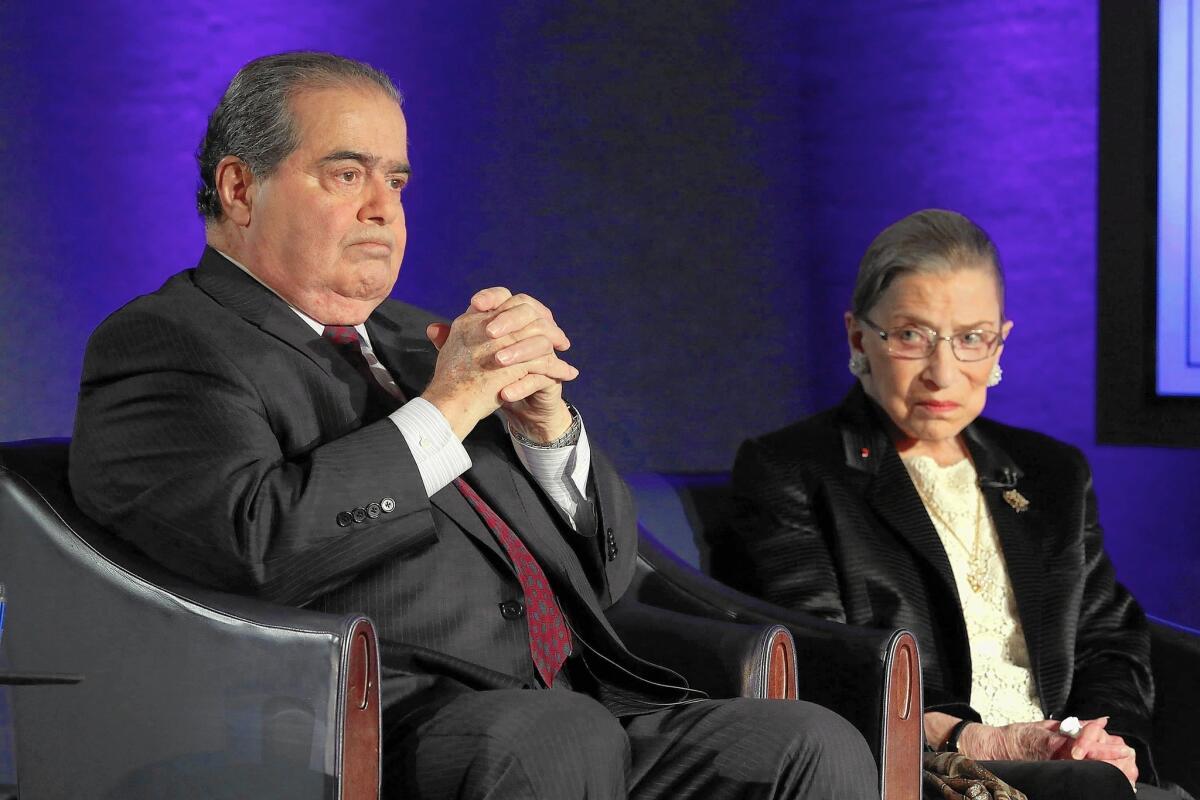

Supreme Court Justices Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg in April 2014. “What’s not to like?” Scalia said of Ginsburg earlier this year. “Except her views on the law.”

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has died at the age of 79. Here is the story that ran in The Times last year on his close friendship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia seem unlikely friends.

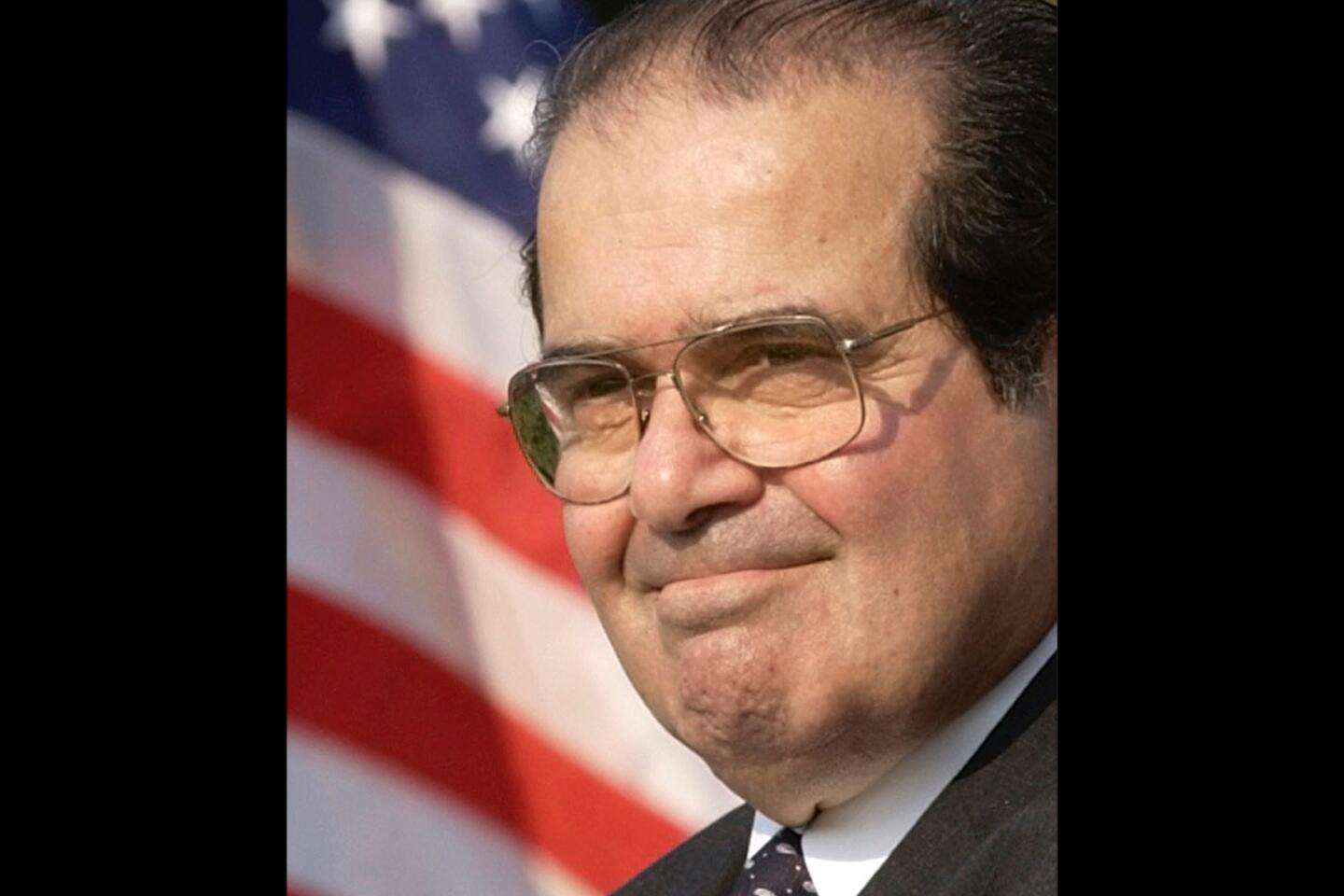

Though both grew up in New York City and graduated from Ivy League law schools, Scalia went on to become a lawyer in the Nixon administration and a founder of the conservative Federalist Society, and Ginsburg led the women’s rights project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

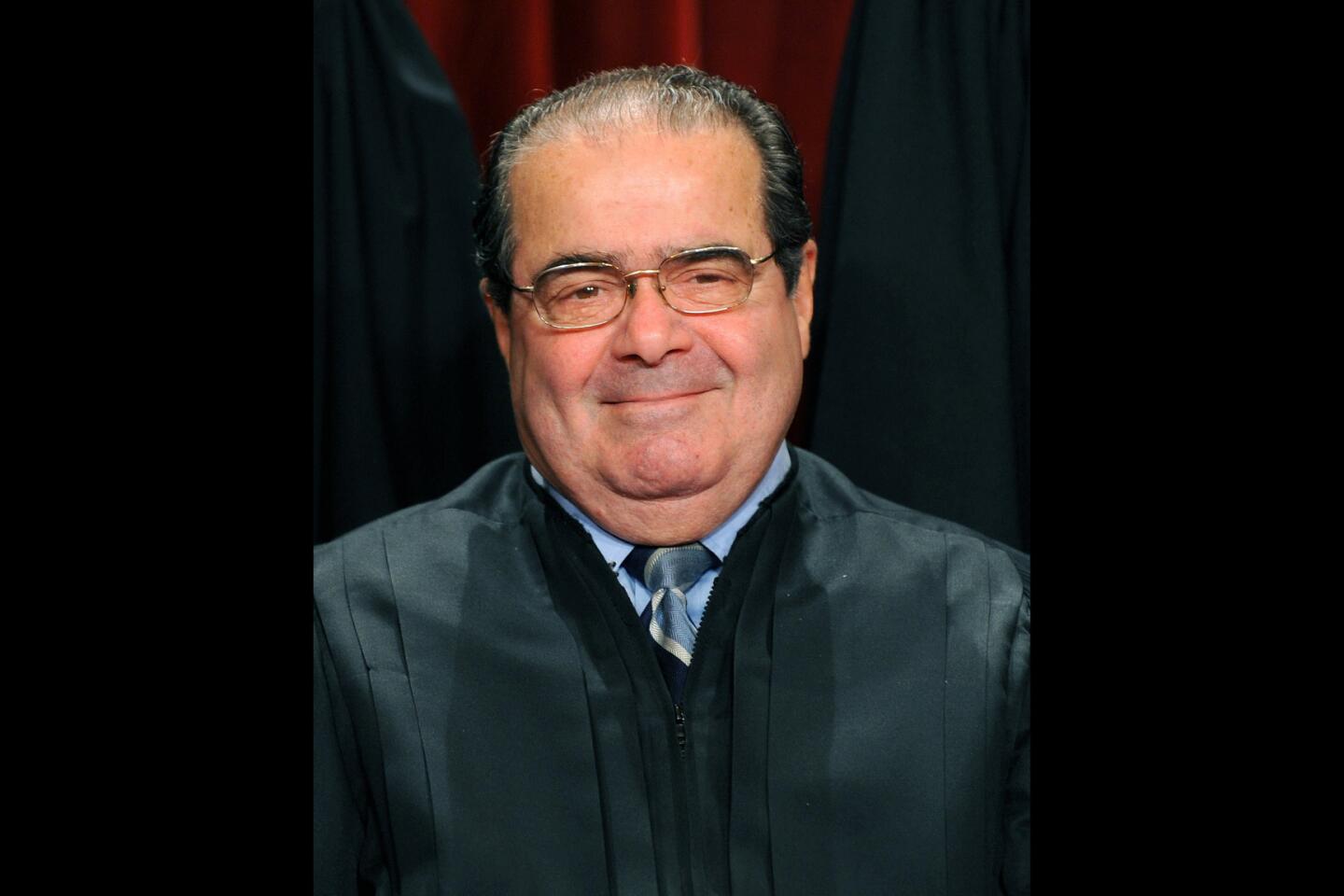

He’s brash and burly and believes in strict adherence to the Constitution’s original text. She’s soft-spoken and slight and believes in a “living Constitution” that can change with the times. On controversial cases, they are often the most likely of any pairing of the nine Supreme Court justices to disagree.

Despite their standing as the intellectual lions of the left and right, Ginsburg and Scalia have forged an uncommon bond on a court where close friendships outside of chambers are rare.

Their areas of agreement may be few — which is likely to be the case this month when the justices decide whether gay and lesbian couples have a right to marry — but they maintain a tone of respect.

Scalia, 79, and Ginsburg, 82, frequently dine and vacation together. Every Dec. 31, they ring in the new year together. Their relationship has even inspired an opera, set to debut this summer.

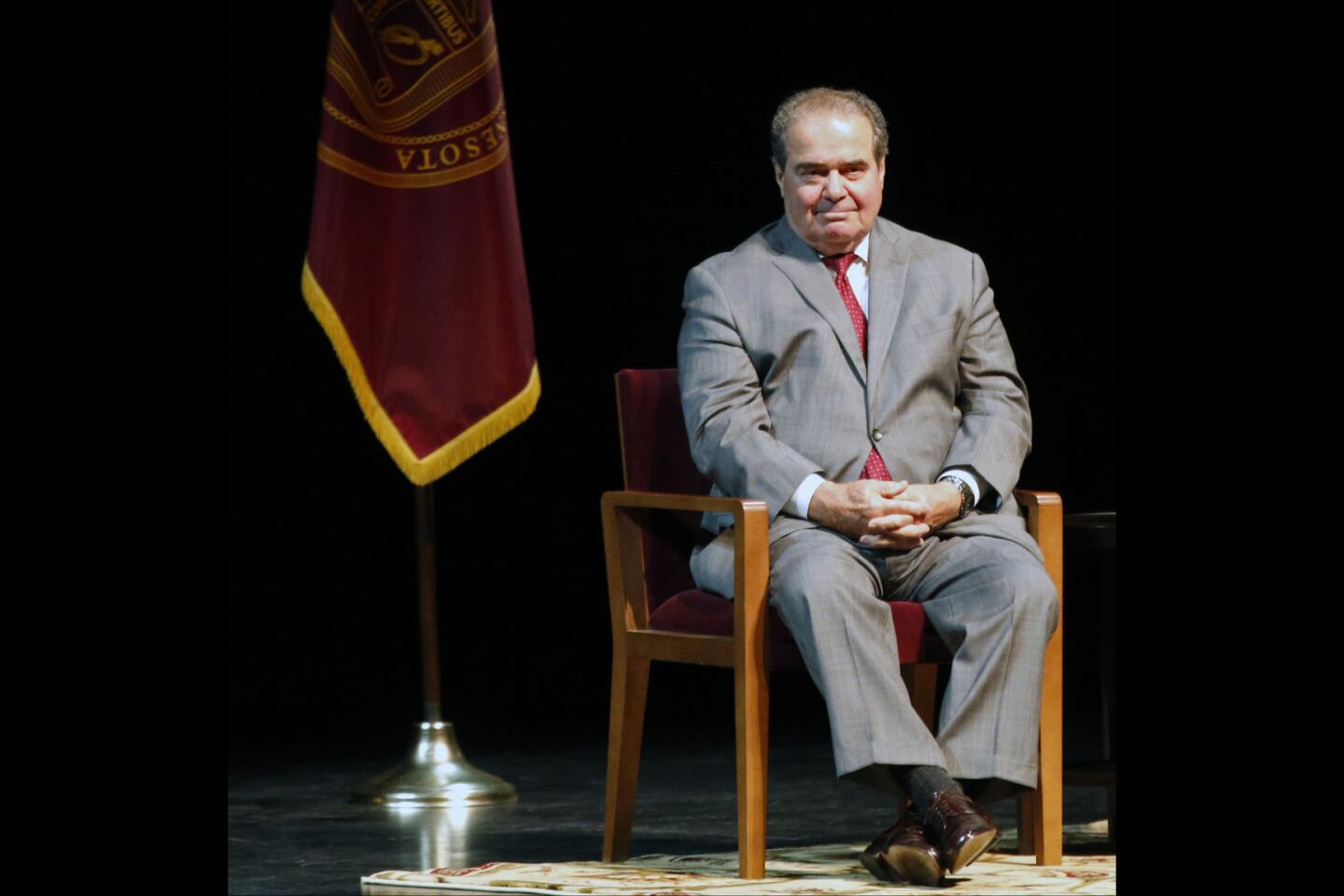

In joint appearances, their mutual affinity and gentle joshing delight audiences, particularly at a time of bitter partisan differences that have made friendships across the aisle difficult.

“Call us the odd couple,” Scalia said this year at a George Washington University event with Ginsburg. “She likes opera, and she’s a very nice person. What’s not to like?” he said dryly. “Except her views on the law.”

Seated next to Ginsburg on the stage, Scalia teased her about the minor uproar that occurred after they were photographed together on an elephant during a trip to India in 1994. “Her feminist friends” were upset, Scalia said, that “she rode behind me.”

Ginsburg didn’t let him have the last word, noting that the elephant driver had said their placement was “a matter of distribution of weight.” The audience, including Scalia, roared with laughter.

She describes her fondness for “Nino” by recalling the time she first heard him speak at a law conference, before they became judges. “I disagreed with most of what he said, but I loved the way he said it,” Ginsburg recounted.

The pair met in the early 1980s as judges on the U.S. appeals court in Washington; Scalia joined the Supreme Court in 1986 and Ginsburg followed in 1993.

He may have even played a small role in her appointment.

With President Clinton pondering his first nomination to the high court, Democrats were anxious to find someone who could do battle on equal terms with the court’s dominant conservatives.

A story went around Washington legal circles that Scalia’s clerks had asked him at lunch: “If you had to spend the rest of your days arguing with Mario Cuomo or Laurence Tribe, who would you choose?” The New York governor and the Harvard law professor were being talked about as leading candidates.

Scalia supposedly replied, “Ruth Bader Ginsburg.”

A few weeks later, the president announced her as his choice.

Lisa Blatt, a lawyer who argues regularly before the high court, said the judges had been close back when she clerked for Ginsburg in 1990. When Ginsburg’s husband, Martin, and several clerks arranged a small party to celebrate her 10th year on the appeals court, only one justice came by: Scalia.

Their friendship, Blatt said, is based on mutual respect and common interests that transcend their ideological differences.

“I don’t think they even try to influence each other,” Blatt said. “Both of them simply have huge personalities, love the arts, like to laugh and are brilliant.”

Ideology aside, Scalia has said he and Ginsburg are “legal academics” who appreciate good writing and well-reasoned arguments. He once recalled that as a new appellate judge, he sometimes sent colleagues memos critiquing their reasoning in a particular opinion. Most often, he said, his missives were not appreciated.

But Ginsburg, who had taught at Columbia University before joining the District of Columbia Circuit, was glad to debate and welcomed his comments.

Their off-the-bench friendship grew over time, aided by Ginsburg’s husband. By day he was a Georgetown law professor and one of the nation’s foremost experts on tax law. But, outgoing and funny, he also was an extraordinary self-taught chef. When Scalia and his wife, Maureen, came for dinner at the Ginsburgs’ Watergate apartment, part of the attraction was the meal Marty prepared.

Shortly after her husband died of cancer in June 2010, Justice Ginsburg came to the court to deliver an opinion. As she spoke, Scalia sat a few feet away, wiping tears.

Other justices do socialize after hours: Justice Elena Kagan has gone hunting with Scalia and to the theater with Ginsburg, and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Anthony M. Kennedy have been seen together at Washington Nationals games. But the Ginsburg-Scalia bond is special.

“She has very warm feelings” for him, said Samuel Bagenstos, a University of Michigan law professor who clerked for Ginsburg. “There is a personal connection with him unlike any of the other justices.”

That friendship has done little to shade or soften their legal views. Scalia has never mocked her opinions in the way that he wrote dismissively of, for example, former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor or Kennedy. But their areas of agreement are few.

Though all the justices typically agree in about three-fourths of cases involving issues like bankruptcy, patents or legal procedure, Scalia and Ginsburg regularly are on opposite sides in matters that divide the nation — including abortion, affirmative action, campaign funding, the death penalty, the environment, gay rights and gun rights.

In summer 2012, when the court ended with a close split on President Obama’s healthcare law and Arizona’s strict immigration law, Scalia and Ginsburg had agreed in 56% of the term’s cases — the lowest rate of any two justices. When only the 5-4 decisions were included, they agreed just 7% of the time.

Ginsburg believes the Constitution’s guarantee of “equal protection” of the laws must evolve with society. In the 1970s, that meant an end to gender discrimination. And this term, she is almost certain to vote in favor of an equal right to marry for gay and lesbian couples.

Scalia insists the Constitution should be interpreted the way its original writers would have understood it. By that standard, he says, no one would say the 14th Amendment in 1868 was adopted to forbid discrimination against gays.

“They have a very different vision of the Constitution and its protection for liberty and equality,” said Duke law professor Neil Siegel. “If Justice Scalia had his way, he would go a long way to destroying her life’s work in sexual equality, abortion, pregnancy discrimination.”

When Ginsburg in 1996 wrote her first major opinion and ruled that the Virginia Military Institute and other all-male public colleges must open their doors to qualified women, Scalia wrote the lone dissent.

And even today, he insists he was right. He told the George Washington University audience that the military service academies have lost their luster as training grounds for “warriors” now that women are enrolled.

“That argument won’t work, Nino,” Ginsburg said, noting that most VMI graduates did not join the military.

Later, when Ginsburg insisted the court’s constitutional decisions should reflect changing social attitudes, Scalia objected. “We’re not going to agree on this, Ruth,” he said.

After the court adjourns for the summer, the pair’s unusual friendship will be on display in a comic opera called “Scalia/Ginsburg: A (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions.” Its composer, Derrick Wang, said he discovered a truly operatic character when he read Scalia’s dissents as a law student at the University of Maryland.

“Whenever I encountered the phrase — ‘Scalia J., dissenting’ — I would hear in my head a rage aria. That’s a type of aria where the character is incensed and expresses anger. It’s a fitting way to introduce Justice Scalia as passionate, disgruntled and rooted in the 18th century,” Wang said.

The opera will premiere July 11 at the Castleton Festival in northern Virginia. It opens with the Scalia character singing, “The justices are blind. The Constitution says nothing about this!” But when he is imprisoned for “excessive dissenting,” help arrives in the form of Ginsburg — breaking through a glass ceiling to rescue him.

Ginsburg plans to attend the premiere. It is “for me a dream come true. If I could choose the talent I would most like to have, it would be a glorious voice. I would be a great diva, perhaps Renata Tebaldi or Beverly Sills,” she wrote in a foreword to the opera. “But my grade school music teacher, with brutal honesty, rated me a sparrow, not a robin.”

As usual, Scalia sees it a bit differently. “I could have been a contendah — for a divus, or whatever a male diva is called,” he wrote in response. He said he has sung in choral groups and once “joined the two tenors from the Washington Opera singing various songs at the piano.... I suppose, however, it would be too much to expect the author of ‘Scalia/Ginsburg’ to allow me to play (sing) myself. Even so, it may be a good show.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.