Who are the ‘Dreamers’ whose dreams have been deferred? You might be surprised

On Sept. 5, the White House announced it was moving to end the Obama-era program that has protected people from deportation. (Sept. 5, 2017) (Sign up for our free video newsletter here http://bit.ly/2n6VKPR)

- Share via

Long ago, it seems,

The recent debate has focused instead on a group of young immigrants who entered the country illegally through no fault of their own — kids who were brought in by their parents or others. Most grew up speaking English, attending U.S. schools, playing on community soccer or football teams.

Are they supposed to be deported? To where? To countries they don’t even remember? President Obama put a foot in the door of immigration reform with an executive order in 2012 known as

Those who benefited from it came to be known as Dreamers.

The Trump administration this week signaled that the program will come to an end in six months, unless Congress takes steps to renew or revamp it — an announcement that has sent new shivers of anxiety through immigrant families across the country.

Who are the Dreamers? They are more diverse than you might think. According to the Brookings Institution, immigrants from 195 countries had applied for DACA status as of 2015. Most were from Mexico. After that, the top five countries of origin were El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and South Korea.

Here are some of their stories.

Melody Klingenfuss

Melody Klingenfuss knew that it was only a matter of time before President Trump would scrap DACA.

She knew the program was “under threat like never before.”

For the last couple of months, this sense of dread fueled her desire to reach out and teach young beneficiaries of the program to fight back against Trump’s crackdown on people in the country illegally.

“Once we connect with them, we show them their rights and how to organize and the importance of organizing,” Klingenfuss said.

Many of the DACA beneficiaries she trained over the summer have lived their entire adult lives with the program and have never felt the need to organize, she said, until now. At first many were shy, but now they are ready to be vocal, she said.

Klingenfuss, 23, of North Hills, came legally to the U.S. from Guatemala at age 9 to reunite with her mother. She fell out of legal status when she overstayed her tourist visa, she said, but was accepted into the DACA program after submitting to a strict screening process. She earned a bachelor’s degree in communications and a master’s in nonprofit leadership and management from USC and is now an immigrant youth organizer with the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights Los Angeles.

We are turning that anger and other feelings into action.

— Melody Klingenfuss

Klingenfuss and other DACA recipients — who receive a Social Security number and work permit — found out Tuesday that the Trump administration had rescinded the program.

She said she’s trying not to focus too much on how the end of DACA will affect her own life. Instead, she’s putting all her energy into galvanizing others to take a stand.

“There is a lot of anger. There is a lot of motivation to really rise up,” she said.

Now, she’s teaching those angry young people the same youth to harness their feelings and use it to help themselves and others in the immigrant community.

“We are turning that anger and other feelings into action,” she said. “That’s our focus.”

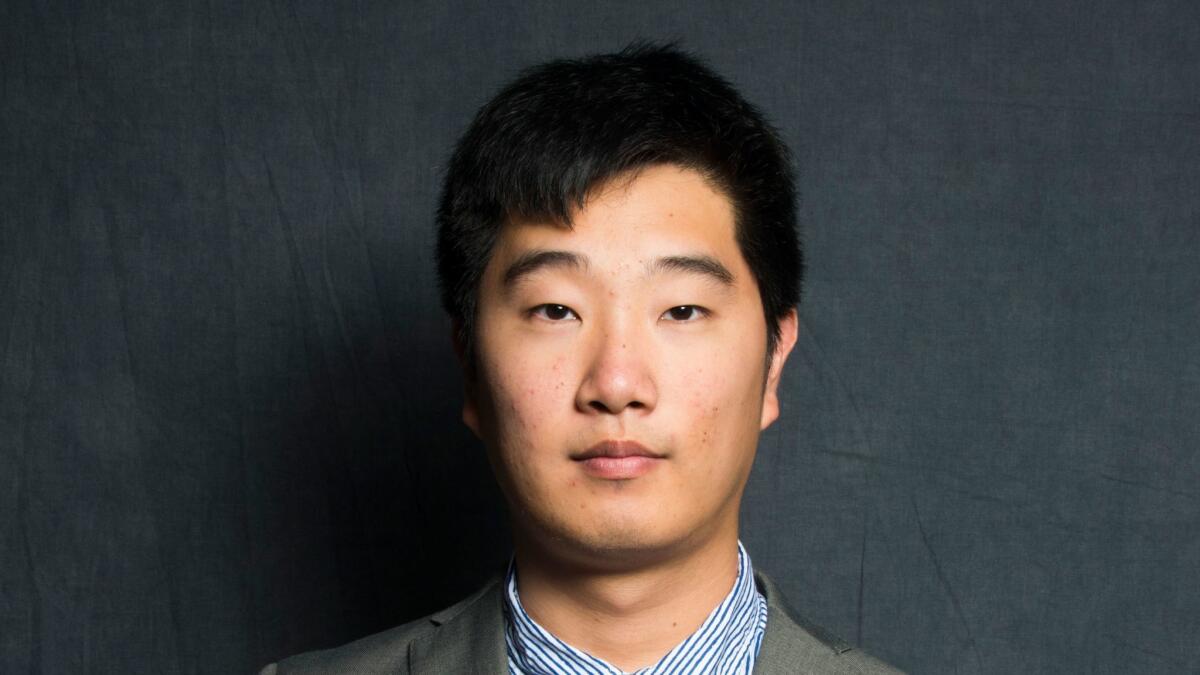

Jeong Park

When he was 11, Jeong Park's parents — a cab driver and a cosmetics saleswoman — sent their only child from Seoul to Southern California on a tourist visa, having saved money to enroll him in a private prep school in Van Nuys.

Park says his mother told him that, as a boy, he really needed to make the trip to explore America. But what he remembers is that he cried a lot on the plane.

He grew up, cared for by an uncle, with whom he still lives in Koreatown in Los Angeles. He graduated from Diamond Ranch High School in Pomona, later earning a political science degree from UCLA. He had no idea of his immigration status, due to his expired tourist visa, until he tried to get a driver's license as a teen.

Now 23 and a DACA recipient, Park struggled with his emotions on Tuesday after hearing the program could end in six months. He said the public may not be aware of the great diversity among DACA recipients.

“I know that most undocumented faces you see are Latino faces. But I hear that there are thousands and thousands of people from other cultures. Not everyone needs to be silent,” he added.

He has been hunting for a tutoring job, a reporting job at a newspaper, or a public relations job at a nonprofit. Now he worries about that job search.

“When people do their research after interviewing you, they will know what your situation is. But I don't want to be in the shadows. There’s not that many undocumented youth who have the power or the opportunity to share their stories — and if I do, I should just do it,” Park said.

Most undocumented faces you see are Latino.... But I hear that there are thousands and thousands of people from other cultures. Not everyone needs to be silent

— Jeong Park

His DACA papers expire in August 2018. Park could choose to be upset, or depressed, but he doesn't. "I'm hopeful. I've seen a lot of statements from Republican congressmen and senators who appear understanding" about the need to keep the DACA program. "Maybe this is one step back, two steps forward.”

He's been getting inspiring messages from friends on social media. And one fact propels him: “The truth of the matter is 12 million immigrants have survived — DACA or no DACA. You're not going to be able to get rid of all of them,” he said.

Park doesn't think about returning to South Korea. He understands his parents sacrificed so he might find success in a professional career in the U.S. This past summer, he finally saw his father for the first time since leaving his homeland. His dad came to his college graduation.

Gregory ‘Ronnie’ James

A “lifeline” — that’s how Gregory “Ronnie” James of Brooklyn had viewed DACA.

“Now that lifeline has been taken away,” he said Wednesday.

James was 9 when his mother — who was living in the U.S. illegally, working as a babysitter — sent for him and his older brother from their Caribbean island home of St. Lucia. In New York, he attended Aviation High School in Long Island City. When his mother heard about DACA in 2012, she urged James and his 24-year-old brother to apply.

After receiving DACA, his brother found work as a security guard, then as a nursing assistant. James enrolled at Borough of Manhattan Community College in a two-year associate’s program in communications, then transferred to City College, where he is a junior majoring in international studies.

“I have a scholarship that’s tied to receiving in-state tuition. If I lose DACA, I can no longer afford school, basically,” James said by phone in between classes Wednesday.

James, 20, was recently hired to intern for a member of New York’s

I don’t think it’s a Latino issue, it’s an issue for immigrants.… A more permanent solution is needed.

— Gregory ‘Ronnie’ James

“DACA was never a permanent solution to fixing the immigrant situation of Dreamers or our parents,” he said, adding, “I don’t think it’s a Latino issue, it’s an issue for immigrants .… A more permanent solution is needed.”

He said the U.S. is at a crossroads and must decide how it treats not only “Dreamers,” but all immigrants, Muslims and people of color.

“Are we the country that makes dreams come true or that takes it away from anyone who is ‘the other’?” James said.

Armando Carrada

Thanks to DACA, Armando Carrada worked three jobs, graduated with an associate’s degree last year and won a full scholarship to study hospitality management at Florida International University outside Miami.

Carrada, 27, started classes last week, but the campus was closed Wednesday due to the impending arrival of Hurricane Irma, another stress on his family.

Carrada’s mother brought him and his younger sister to the U.S. illegally from Oaxaca, Mexico, when he was 7. Now she runs a nursery, but she relies on his youngest sister, a citizen born in the U.S., to drive her to work since she can’t get a driver’s license.

Ending DACA, he said, will mean, “Students are going to lose the opportunity to support their families, not just monetarily.”

His sister and brother-in-law also received DACA, got driver’s licenses and started a trucking business.

“So what happens then? She loses a business that is helping the economy and promising a job to other people,” Carrada said.

His sister also works as an intensive care technician at a local hospital. She just took maternity leave after having her first child two weeks ago, a girl.

“She called me today and she was just freaking out,” Carrada said Tuesday, the day President Trump announced he was ending the program.

His sister has an appointment to renew her work permit for another two years. Carrada’s permit expires in October 2018. He’s not hopeful Congress will save the program by then.

If something was to happen in Congress, I hope that includes a lot more people. I’m a Dreamer, but my mother had a dream when she came to this country, too.

— Armando Carrada

“They just focus on something else and leave this on the back burner,” he said. “If something was to happen in Congress, I hope that includes a lot more people. I’m a Dreamer, but my mother had a dream when she came to this country, too.”

For now, Carrada said he will focus on organizing fellow Dreamers and “making sure people are not in fear.”

“We already came out of the shadows and then this happened. We don’t want people to be like, ‘I don’t want to talk or go to rallies,’” he said.

Pedro Ramirez

Pedro Ramirez’s first act of politics was a walkout in high school after Congress voted against a comprehensive immigration reform bill in 2007.

In the decade since, he said he has learned to remain skeptical about efforts to mend the nation’s broken immigration system — efforts that affect him directly. Born in Jalisco, Mexico, his parents brought him illegally to the United States at age 3.

Like many others, they came seeking a better life, and that extended to their son. DACA has allowed Ramirez, 28, to work legally since 2013, most recently as a labor union organizer.

The Trump administration’s announcement that it would end the program came as no surprise to him.

"This is not new,” he said. “It’s disappointing because when you get something like [DACA], it gives you opportunities. Getting it taken away is a shock, especially for younger generations who didn’t have to hustle as much as we did back in the day. People like me, we figured it out. We can survive. But it sucks — it sucks a lot.”

Ramirez, 28, worked odd jobs and used scholarships to finish his bachelor’s degree in political science at Fresno State and his master’s in public policy and administration from

After receiving his work permit, he got his first steady job with Los Angeles City Councilman Gil Cedillo’s office. Now he works as a campaign coordinator for a union organizing group in Fresno. DACA has meant full-time employment and healthcare.

Getting [DACA] taken away is a shock, especially for younger generations who didn’t have to hustle as much as we did back in the day.

— Pedro Ramirez

Ramirez and his parents, a restaurant worker and a hotel maid, are the only members of his family without permanent legal status. His younger brother was born in the U.S.

Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, Ramirez began preparing for a worst-case scenario. He put more money into his savings. He and his parents made copies of their important legal documents and forms of identification, wrote down emergency contacts and made copies of their house keys to give to people they can trust in case any of them is detained. Ramirez also plans to add a family member with legal status as a co-signer on his car loan.

It’s not as if he’s in hiding. In 2010, shortly after being elected student body president of Fresno State, Ramirez’s immigration status was publicly exposed in an anonymous email sent to local news outlets.

“In a way, I'm relieved,” he told The Times then. “I never really thought this was going to happen. But now that it's out there, I finally feel ready to say 'Yes, it's me. I'm one of the thousands.’”

Dulce Gomez

Dulce Gomez, 19, didn’t realize she was any different from any of her friends or her siblings until she was in high school and thinking about college.

Brought to the United States from Mexico when she was 2 years old, she’d spent her whole life, or at least what she could remember of it, living in Newark, N.J. Her younger siblings were both U.S. citizens.

“I’m the only one born in Mexico. But I never really thought about it. As a child, I just thought this is my country. This is where I’m from.”

That changed when she took the SAT in preparation for going to college. “There were these questionnaires about applying for financial aid and scholarship. I asked my mother and then I realized.”

Gomez, a DACA recipient, got into Kean College in Union, N.J., and she is starting this month, studying political science. “I figure I have one semester to study in the United States.” But she canceled her plans to start driving lessons, since she decided there is no point in getting a New Jersey driver’s license.

The ordeal, though, has strengthened Gomez’s relationship with her friends and siblings. “One of my friends told me, don’t worry, I can hide you in my dorm room.”

As a child, I just thought this is my country. This is where I’m from.

— Dulce Gomez

On Monday night, anticipating President Trump’s announcement the next day, Gomez’s 13-year-old brother cried with her. “He hugged me for what might have been 30 minutes to say goodbye.”

Gomez, though, is not quite ready to give up. She has become an activist and is speaking up at rallies about young immigrants like herself. “Even in the immigrant community, our immigration status used to be something that we didn’t talk about. But I’m not afraid anymore. I’ve found my voice.”

Stephanie Ji Won Park

Stephanie Ji Won Park was born in Seoul and arrived in New York when she was 5.

Once the tourism visa her parents used to travel to the United States expired, they settled into an apartment in the Bronx. She earned scholarships to attend some of the best private schools in New York.

In middle school, as classmates traveled abroad, Park’s parents would not allow her to go along. Slowly, she began to realize she was in the country illegally.

She applied and became protected under DACA in 2013.

“It felt great,” she said. “It offered some security.”

Immigrants from South Korea, after those from Mexico and Central America, are among the biggest participants in the DACA program.

“This issue greatly affects Koreans,” she said. “It’s not brought to light that much, but it does.”

Two years after achieving “Dreamer” status, Park received her bachelor of arts in English, history and media from Hunter College in Manhattan. Now 24, she’s a board member at United We Dream, an immigrant rights group based in Washington.

When she heard about the Trump administration’s decision to end the program, Park wasn’t surprised.

Since the November election, she had prepared for it to end.

“It’s still just emotionally and physically exhausting,” she said. “It’s painful.”

Are you a DACA participant? Tell us what you think of Trump's decision to end the program »

Angel Ortega

Angel Ortega, 27, doesn’t want to be deported, but he will be ready if it happens.

He’s working overtime to finish a master’s degree in higher education at Queens College in New York with the hopes that an advanced U.S. degree will get him a job if he lands back in Mexico. At the same time, he teaches Spanish and gym at a Catholic school and coaches track and field in order to support himself.

And if that didn’t keep him busy enough, Ortega is training to run in the New York City marathon.

The consummate New Yorker — with the New York accent to prove it — Ortega grew up in the Astoria neighborhood of Queens after being brought to the United States as a 4-year-old. Although most federal and state scholarship programs did not accept undocumented immigrants, Ortega has the advantage of his athletic abilities.

“It was extremely hard to get into college, but I was one of the best runners,’’ he said. He majored in exercise science and kinesiology.

Ortega thought his life had gotten easier in 2012 when he was approved for DACA, but was crushed by Trump’s victory in the presidential election.

I was completely broken. I cried the entire night

— Angel Ortega, on the election of Donald Trump

“I was completely broken. I cried the entire night,” Ortega said.

Since November, Ortega has followed every utterance from Trump about whether to continued the deferrals for young immigrants like himself. He is not optimistic that Congress will act within the six-month period given by the White House to restore the program.

“Given that the Republicans have no spine and that they don’t want to condemn the president for supporting white supremacists, I think the chances for us are very slim.’’

Sumbul Siddiqui

Sumbul Siddiqui, who does not have health insurance, dreams of advocating for this "most basic of rights" for people in the country illegally.

She also dreams of becoming a doctor, and her enrollment in DACA seemed a step toward meeting that goal.

Born in Saudi Arabia to Pakistani parents, and now living in Atlanta, she works as a medical scribe, handling records and taking notes for doctors examining patients. She's also a volunteer at a low-income community clinic, where she's been able to digitize all the paper charts amassed from steady streams of immigrant and local clients.

“What led me to medicine is the lack of access we have to knowing what's going on and what we can do to take better care of our health. We're part of the underserved simply because we're undocumented,” Siddiqui said.

She earned a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience from Agnes Scott College in Georgia and is now taking a gap year before applying to medical school in hopes of working with marginalized populations that “need our help more than ever.”

Trump's rejection of DACA, she says, “doesn't make me so angry. More than anything, I feel hurt — and that hurt pushes me to try harder. A lot of people assume that the undocumented are this way or that way, but the reality is we're all different and we’re from different races. As a recipient, we have nothing to hide because when we apply to DACA, we go through background checks and we open up our lives to the government.”

More than anything, I feel hurt -- and that hurt pushes me to try harder

— Sumbul Siddiqui, on the demise of DACA

Her message to the American public is to “please, don't make assumptions” about those without legal papers. “Really get to know us.”

Siddiqui has lived in Georgia for 20 years, arriving as a 4-year-old on a journey that unfolded when her father, a former travel company manager, applied for a tourist visa that later changed to a business visa when he decided to open a gas station in the state. Now the Siddiqui siblings have mixed immigration status, with her and a younger brother classified under DACA, while two other siblings were born in the United States.

“My mother had heard of these great American opportunities here and she always pushed for us to have the best education,” Siddiqui said, having promised her parents not to lose sight of that ongoing goal. “This is why I decided to speak up. There's a lot of fear, but if you don't speak for yourself, who knows you as well?”

Anayeli Marcos

Anayeli Marcos, 23, has been working to put herself through school at the

“I have some scholarships that cover the cost of school. But a lot of the money I get from work is what actually pays for my education, living in my own place, my survival, buying food and paying the bills,” she said. “DACA ending will mean I can’t work.”

Her work permit expires in April. Her parents live in Houston, where they have been making repairs after their kitchen ceiling caved in during Hurricane Harvey.

“My employer is very understanding, and she’s trying to find a way to continue helping me despite not having this work permit,” Marcos said. “I am hopeful that Congress will eventually do something and act now that Trump has taken the first step, but I’m not depending on it.”

Marcos came with her mother from Guerrero, Mexico, to Houston when she was 6 years old to meet her father for the first time. He worked construction. Her mother cleaned houses. Now she has three younger siblings, all U.S. citizens.

Marcos wasn’t surprised by Tuesday’s announcement ending DACA, which she had been waiting for since Donald Trump was elected in November. “We knew this was inevitably going to happen, but it’s still heartbreaking for people who depend on the program,” Marcos said.

Just because DACA has ended doesn’t mean I have to stop pursuing what I want to do.

— Anayeli Marcos

She spoke by phone from Austin hours after Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions announced Trump’s decision to phase out DACA. She was on her way to a student gathering on campus to discuss how they would react to the announcement.

Marcos said she planned to do everything she could to stay on track to graduate and become a social worker.

“Just because DACA has ended doesn’t mean I have to stop pursuing what I want to do,” she said.

Times staff writers Cindy Carcamo, Andrea Castillo and Kurtis Lee contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

Sept. 6, 7:25 p.m.: This article was updated with a profile of Anayeli Marcos.

5:40 p.m.: This article was updated with profiles of Angel Ortega and Sumbul Siddiqui.

3:40 p.m.: This article was updated with an additional profile.

2:05 p.m.: This article was updated with additional background information about the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

This article was originally published at 1:35 p.m.

FOR THE RECORD

Sept. 7, 10:30 a.m.: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said Sumbul Siddiqui had overstayed her visa. She did not.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.