White House threatens to put brakes on alternative fuels

- Share via

Reporting from WASHINGTON — As biotech masterminds and venture capitalists scramble to hatch a new generation of environmentally friendly fuels that can help power the average gasoline-burning car, they are confronting an unexpected obstacle: the White House.

Yielding to pressure from oil companies, car manufacturers and even driving enthusiasts, the Obama administration is threatening to put the brakes on one of the federal government’s most ambitious efforts to ease the nation’s addiction to fossil fuels.

The proposed rollback of the 7-year-old green energy mandate known as the renewable fuel standard is alarming investors in the innovation economy and putting the administration at odds with longtime allies on the left.

California Gov. Jerry Brown is among several prominent politicians in the West who have personally appealed to the administration to drop the rollback plan championed by the Environmental Protection Agency.

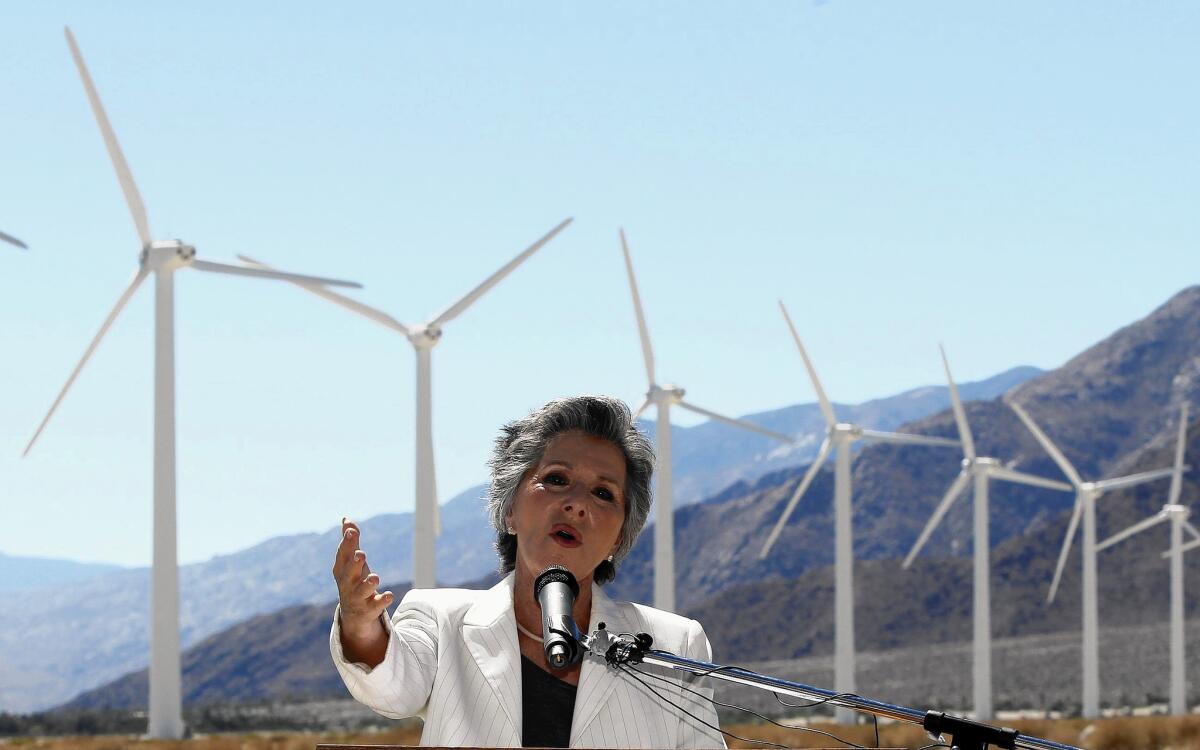

Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) asked the president to stop the EPA from proceeding, warning in a letter last month that the plan destabilizes state efforts to combat climate change and creates “loopholes for oil companies” to avoid reducing pollution.

But the administration is balancing a robust agenda to fight climate change with an alternative fuels program hobbled by setbacks and the messy politics of ethanol.

“This policy is flawed and broken,” said Bob Greco, an executive at the American Petroleum Institute, an industry lobbying group. “The advanced fuels that Congress intended to be made under it just don’t exist yet.”

The alternative fuels mandate, which requires that escalating amounts of ethanol and other biofuels be blended into the nation’s gasoline supply, was meant to spur the creation of environmentally friendly forms of the additives.

These advanced biofuels were supposed to eventually supplant — or at least compete with — corn ethanol, which is spurned by environmentalists because of the amount of energy it takes to grow and process corn, as well as its potential to drive up food prices.

Investors are bankrolling plans to manufacture biofuels from energy-efficient crops and agricultural waste such as corn husks, algae and even forest brush. But manufacturing facilities have been slow to get up and running. There is little of the advanced product on the marketplace.

Corn ethanol is filling the void. And more and more of it is getting blended into the gasoline supply under biofuel quotas that increase each year.

Auto enthusiasts, led by the American Automobile Assn., are protesting in Washington that ethanol causes engine problems. The point is very much in dispute, but some auto manufacturers are threatening to void warranties if the proportion of ethanol in standard gas continues to rise.

Such concerns are at the root of the EPA’s decision to slow the program. EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy says the nation’s gas supply is saturated with as much ethanol as it can handle.

Environmentalists say the outlook is misguided. The fuel standard, they say, is among the administration’s most powerful tools to combat climate change. They want the EPA to use it to prod innovation in the auto and gasoline industries that would allow for more biofuel at filling stations.

“It is disheartening to see how much potential to slow climate change we are missing out on by not doing this,” said Ryan Fitzpatrick, a clean energy advisor at Third Way, a Washington group that seeks bipartisan policy solutions.

Back in the biotech labs of California and the agribusiness offices of the Midwest, innovators say the EPA’s course change is undermining their efforts at a crucial time. The nation’s first two plants producing ethanol made from corn cobs, husks and stalks began churning the fuel in Kansas and Iowa only weeks ago.

Corn ethanol factories, including at least a couple in California, are rolling out modifications to their facilities that enable them to manufacture fuel from such crops as sorghum, a fast-growing, drought-tolerant grain.

Brown and Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, in a letter to the administration this month, cautioned that the work of scientists focused on creating low carbon fuels out of algae and other fast-growing plant matter is jeopardized by the EPA’s approach.

Brown is particularly concerned because California has its own alternative fuel mandates hooked to the state’s landmark global warming law. They were meant to work in tandem with the federal rules.

The viability of at least 25 advanced biofuels projects receiving a total of more than $100 million in state funding is threatened by the administration’s plan, according to California regulators.

“We have the ability to produce this great product, but now we can’t sell it,” said Eric McAfee, a venture capitalist and chief executive of Aemetis, a California ethanol firm that retrofitted a factory to make fuel from sorghum.

“Our ability to increase production of this cleaner, domestic, renewable fuel is eliminated,” he said. “It disappears when we can no longer sell the product.”

McAfee’s firm, a diverse, $220-million operation selling ethanol around the world, will probably survive the shift in federal strategy. Smaller players in California may not.

In San Diego, Jennifer Case, chief executive of New Leaf Biofuel, says her once-thriving company is struggling. It manufactures biodiesel out of cooking oil from hundreds of industrial kitchens in Southern California.

The federal guidelines require that such products be blended into some of the diesel sold in gas stations, as well as sold in its pure form for vehicles equipped to run on it.

But the EPA proposal ratchets down the mandated amount. Gasoline manufacturers slowed their purchases in anticipation that the rule would pass. Case said there was now an oversupply of the product nationwide.

In May, she started laying off employees. Her staff is down to 15, less than half her workforce last year.

“We are just kind of hanging on,” Case said. “We could produce the fuel, but there wasn’t demand for it. ... I couldn’t afford to pay my employees.”

Twitter: @evanhalper

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.