‘You aren’t prepared for something like this’: Loved ones cope with loss in Orlando massacre

- Share via

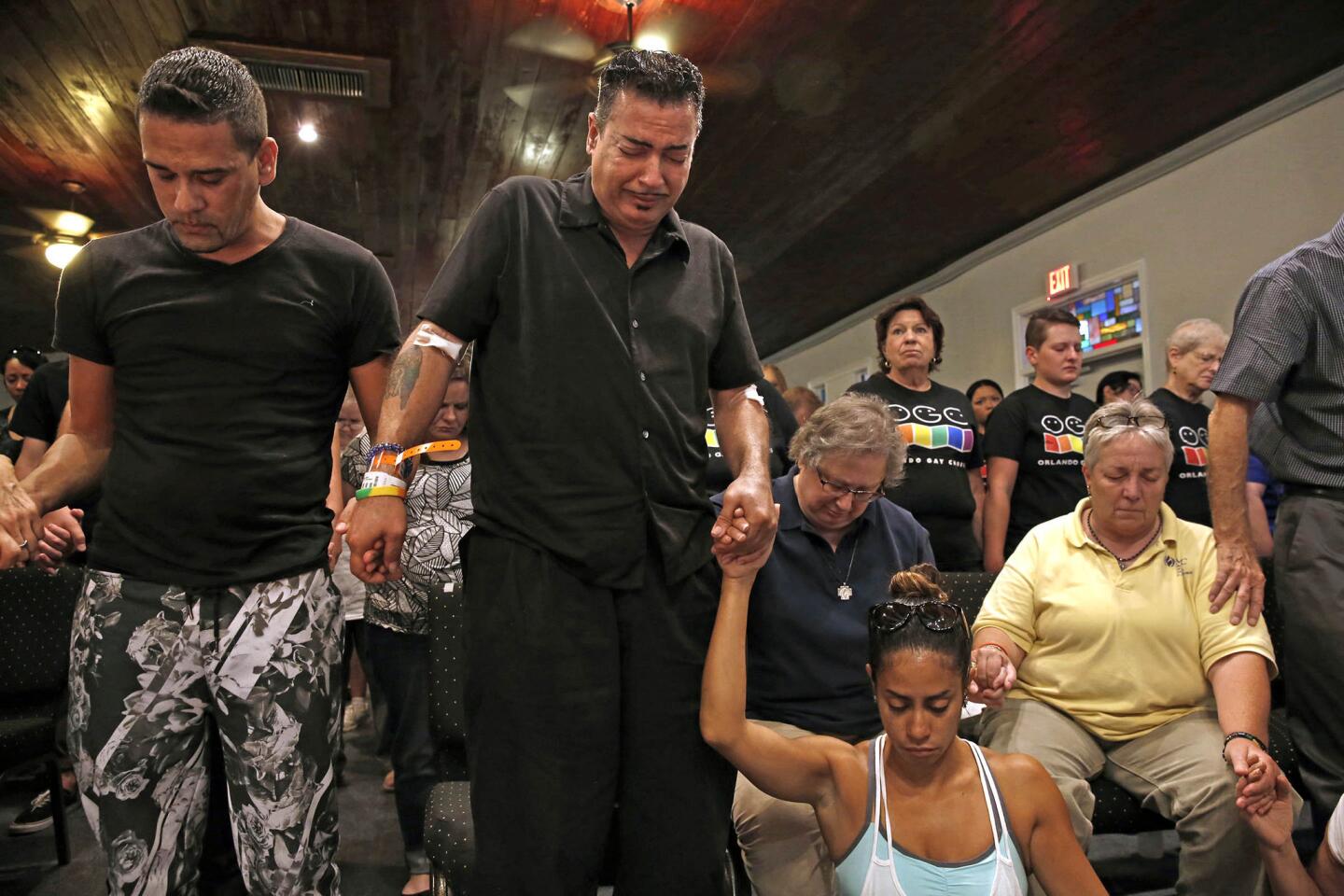

Reporting from Orlando, Fla. — How do you grieve a son, a daughter, a sibling, taken suddenly from you?

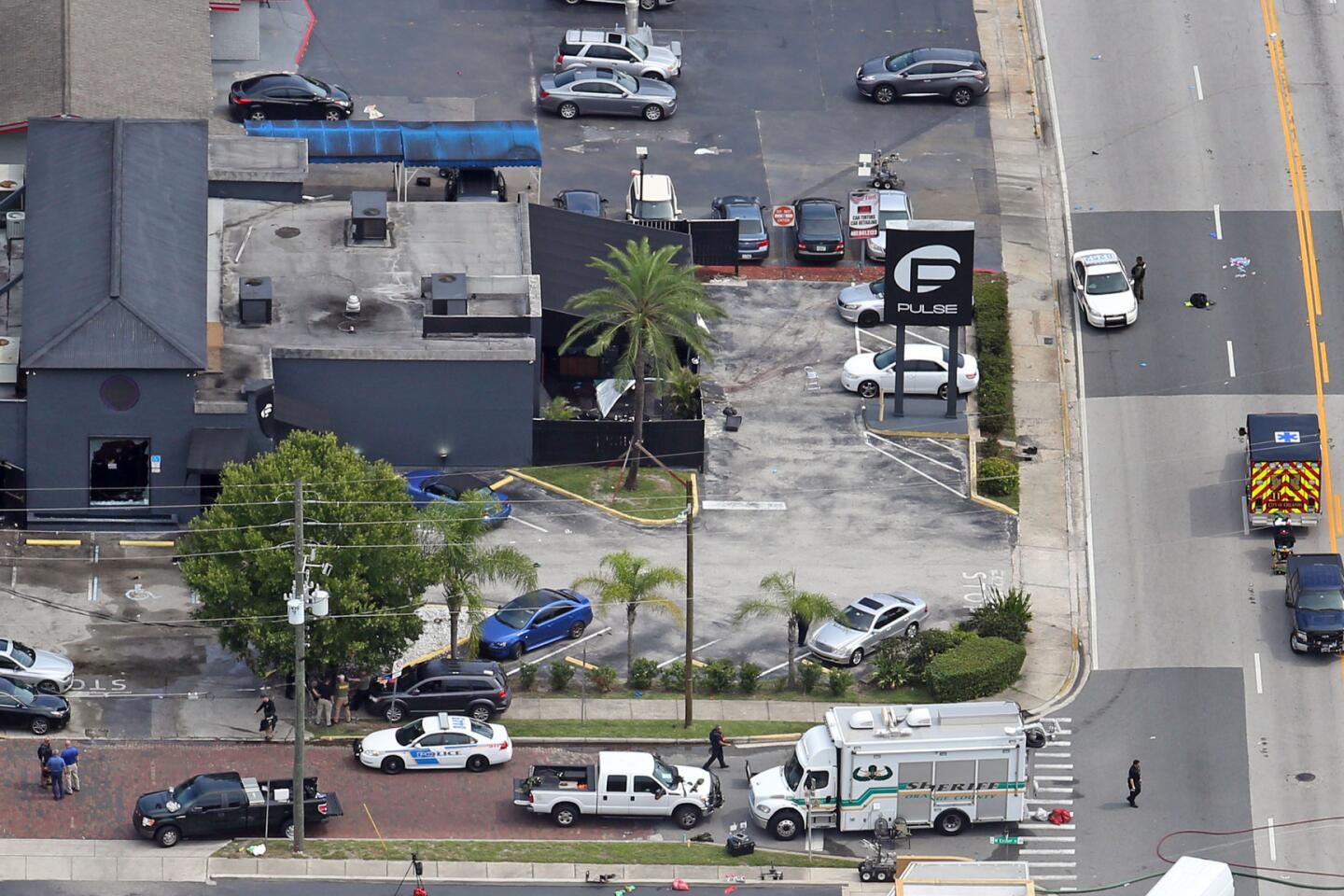

For scores of people who lost loved ones in the massacre at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., on Sunday, that question plagues them.

Whatever gunman Omar Mateen’s motives, 49 families have been left with anguish and regret.

Giovanni Nieves lost five friends at Pulse, including two close fellow drag performers.

“We shared a passion for entertaining,” Nieves said of his two slain friends, Leroy Valentin Fernandez and Anthony Luis Laureano Disla. “It’s what brought us together. I’d go watch their shows, and they’d come see mine.”

It was a form of performance known as “drag extravaganza,” Nieves said. “It was over the top: over-the-top costumes, over-the-top drag.” On Saturday, they were impersonating Latina divas in honor of the gay club’s “Latin Night.”

Roy, as he called Fernandez, was “happy-go-lucky, always smiled. He’d get serious, then crack a smile. He loved the stage.”

Laureano Disla “was an amazing person. He was always fun. Wherever there was music, he would start dancing — whatever kind of music. He was just happy, and he loved what he did.”

Nieves wept quietly as he placed white roses and carnations at a memorial on the lawn of Orlando’s performing arts center.

Most of the victims were originally from Puerto Rico. Four were from Mexico, according to the Mexican government.

Mexican citizen Rufina Paniagua, 54, is the mother of Joel Rayon Paniagua, 31, who was killed at Pulse. He was her sustenance, she said in a telephone interview. She was filling out paperwork to travel to Florida from Mexico and to see her son’s remains.

“My son was a good kid,” she said. “He always worried about me, sent me money. His father abandoned us, and Joel was always taking care of me money-wise. … I don’t understand how someone could do this.”

Paniagua said her son lived and worked in Florida for about nine years, then returned to their home in Mexico’s Veracruz state several years ago. There, he worked at a fruit stand in the market but made so little money that he wanted to return to the U.S., his mother said.

“I told him to stay, to work here, but he had his dreams, his goals,” she said. Joel returned to Florida in August.

Paniagua spoke to her son on Friday. He was worried about her, she said, because he had heard terrible news about “people killing each other in Mexico.”

Paniagua said her son worked in Florida as a gardener and was saving money to help her get a passport and travel to the U.S. Thanks to him and his earnings, she said, she has been able to buy a house and a car.

“The [state] government contacted me [about the killing], and I prayed to God that it was not him,” she said. “I just want to have him here, to bury his body here, although I still have a hope that it may not be him.”

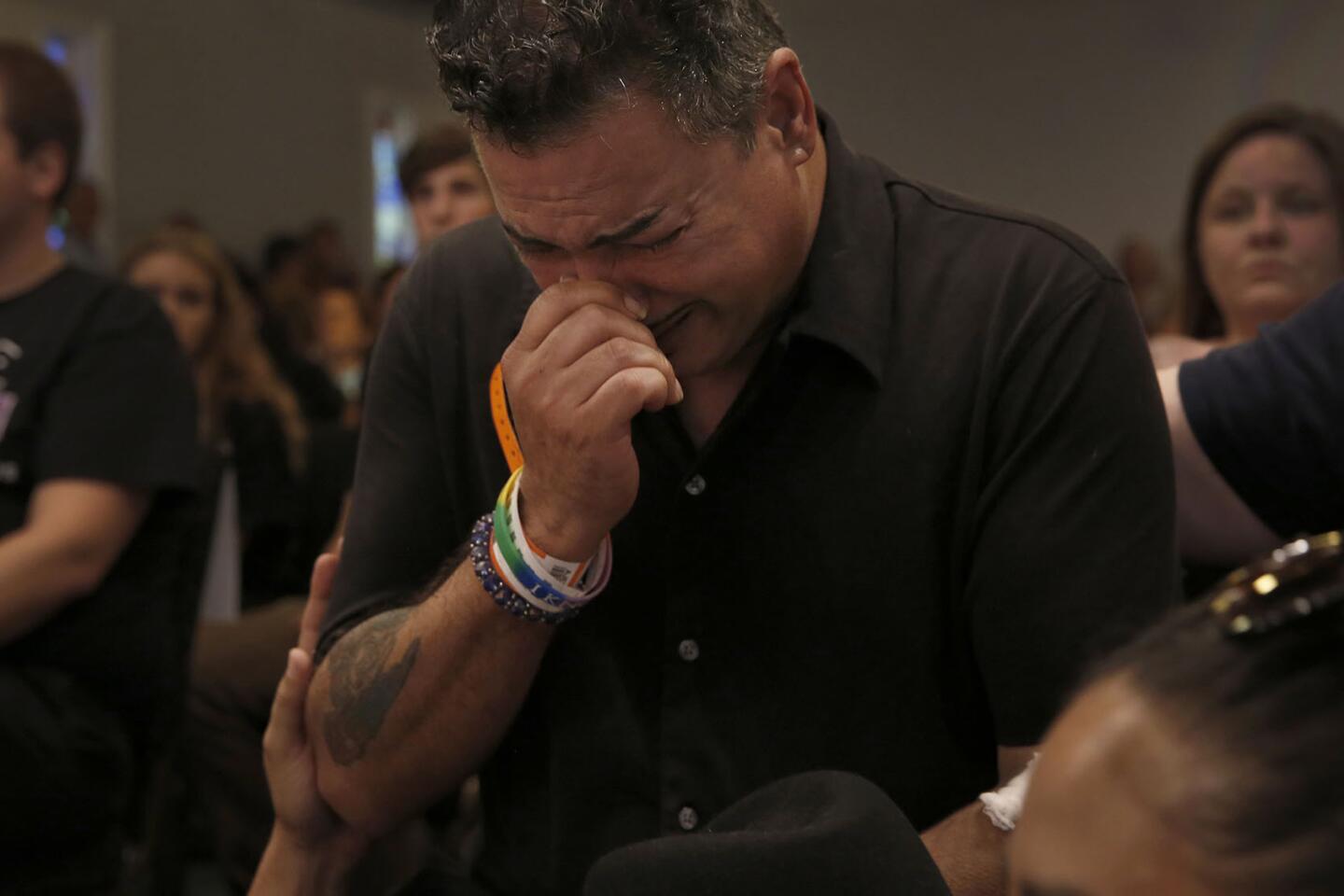

At a seniors’ center not far from Pulse, families of victims were being summoned and, in most cases, given the formal notice that their loved one was among the dead.

They would file in, as couples clinging to each other desperately, or in larger groups of extended relatives, passing under a large awning that read “Welcome” next to a hand-lettered sign saying “Pulse families.” Hours later, they would leave, some sobbing, embracing or rushing away. A black funeral parlor van arrived at one point.

“We know a little bit, that she was hiding in the bathroom,” Cesar Flores said of his daughter, Mercedez, 26. Unlike some parents, Flores said he did not receive a frantic last-minute email or any other indication of what happened, but he started to look for Mercedez when he did not hear from her Sunday. He spoke to reporters after emerging from the center.

Sadness ringed his weak voice. He said he dreaded having to take his wife to identify their daughter’s body.

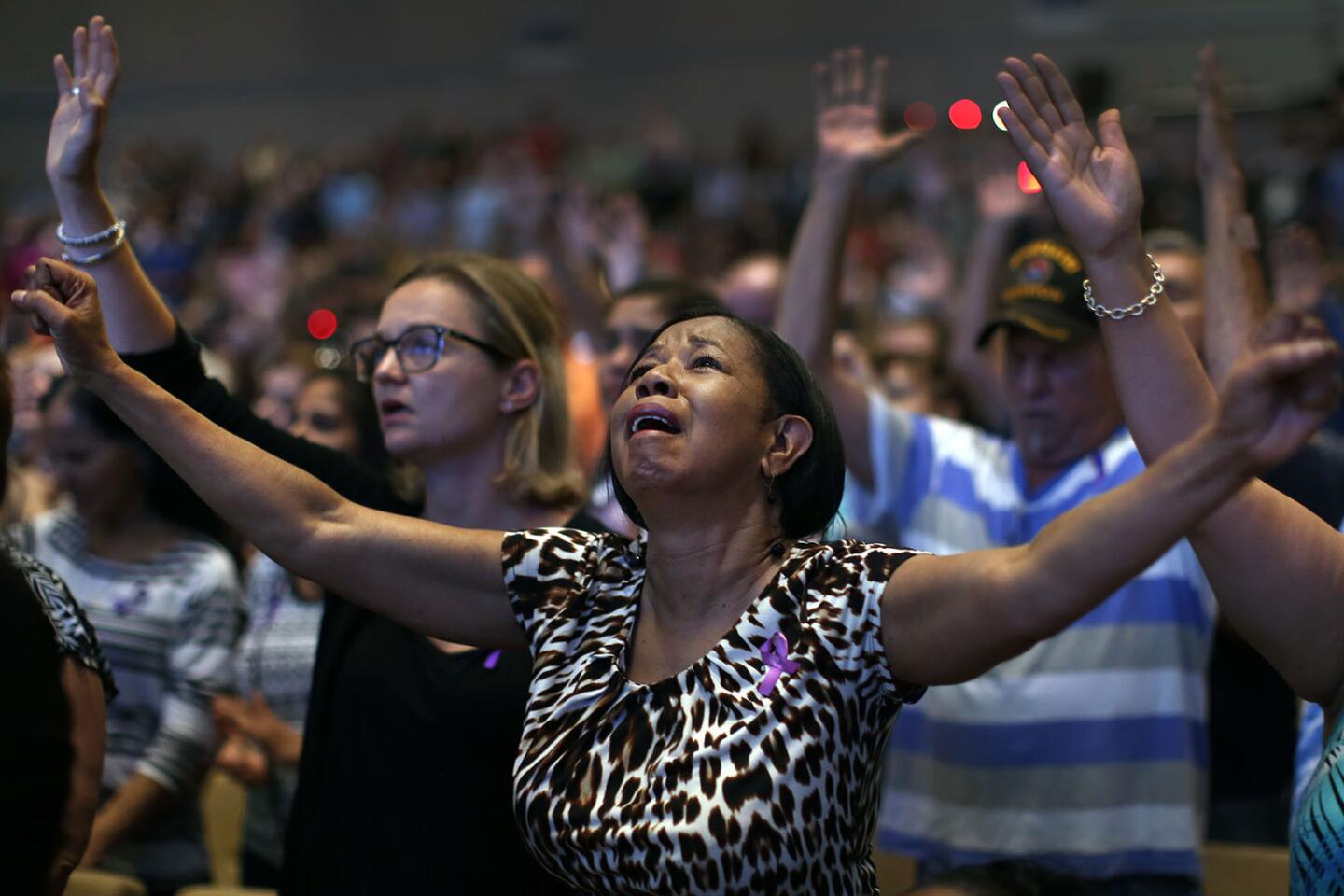

Bishop Daniel Rogers, a Pentecostal preacher, was among several clergy brought to the center to counsel families.

“I find out how much you aren’t prepared for something like this,” Rogers said. “We try to tell them they must continue living.” Why the tragedy happened, he said, “doesn’t even really matter.”

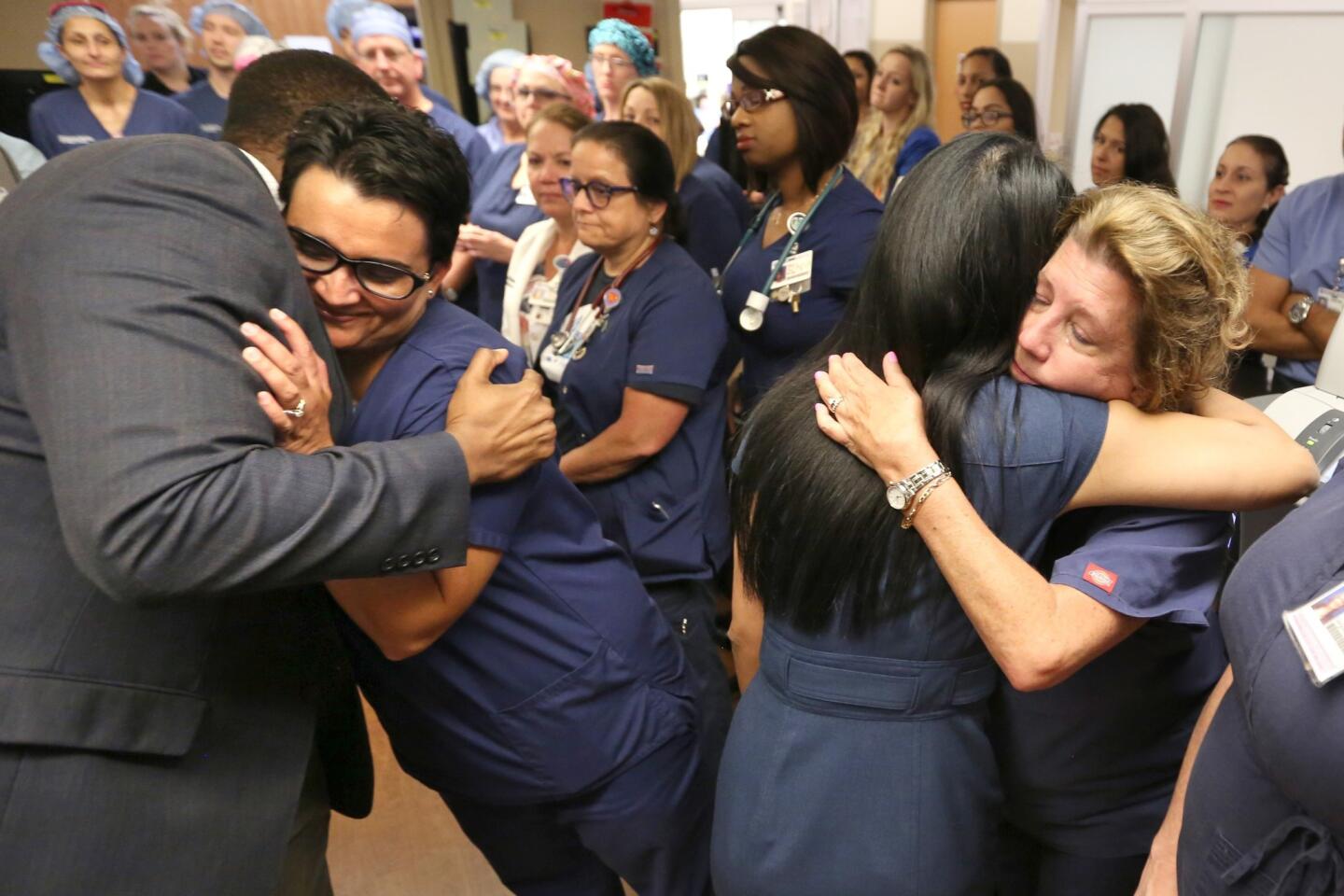

In the lobby of the Orlando Regional Medical Center, families of surviving victims gathered in knots, some weeping, all with faces drawn by worry.

One woman had just arrived from Puerto Rico to see her son, who was about to undergo more surgery. He had sent out messages as he cowered in the bathroom that night at Pulse with a young woman. “I’m losing a lot of blood,” he posted after being shot. “I love you all!” The family thought he was kidding — he was a known jokester — and only later understood the gravity of the situation.

Another family appeared to have bought out the hospital gift store of all its balloons for a friend and relative, a young man named Brian, who was recovering from gunshot wounds. (Like many interviewed, the person did not want his full name published.) One balloon said, “Happy Birthday,” another said “It’s a Boy!”

The friends said they, and Brian, liked to joke that way. Besides, said one, “I feel like he’s been born again.”

Cecilia Sanchez in The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

MORE ON ORLANDO SHOOTING

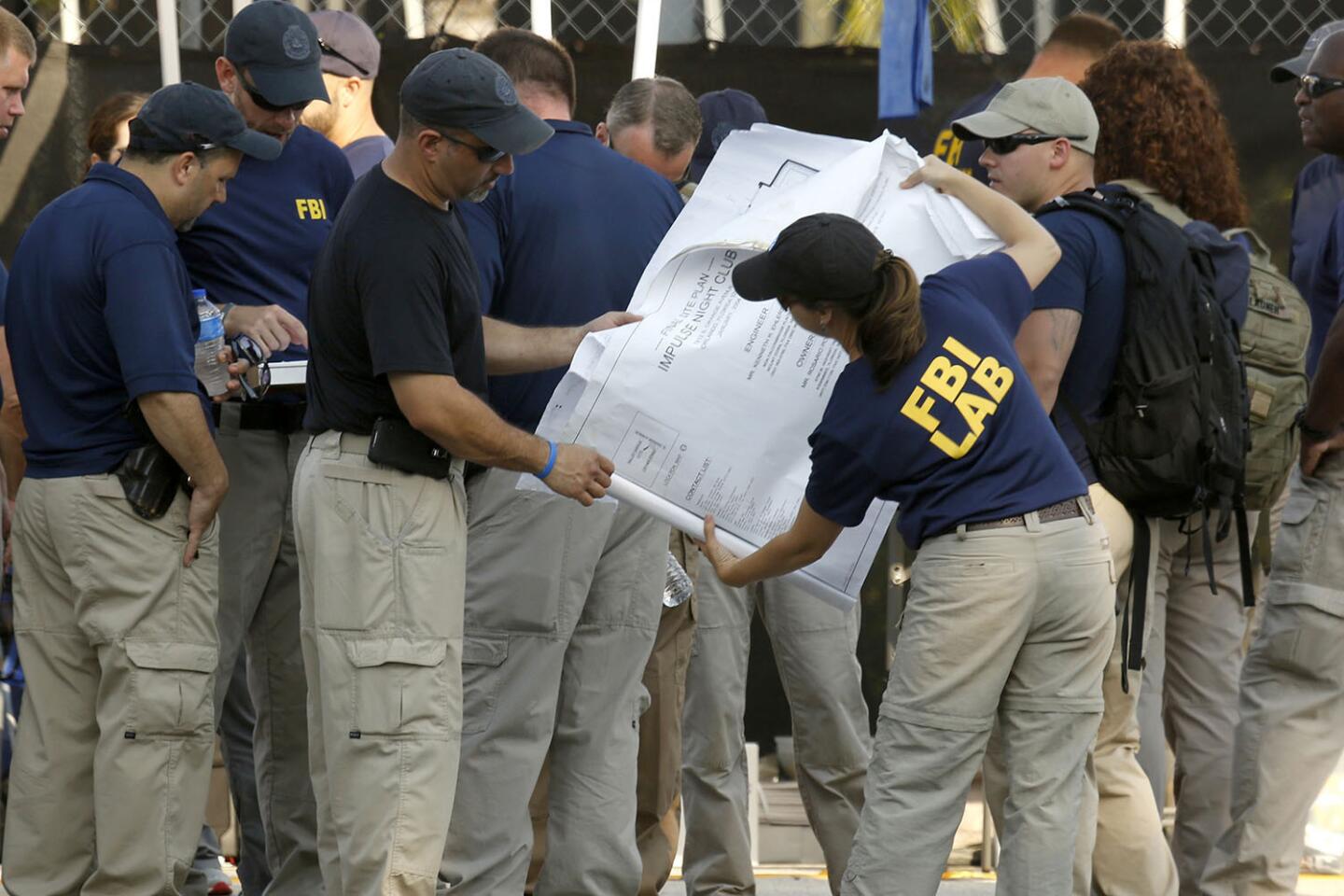

A night of terror: How the Orlando nightclub shooting unfolded

A small Florida town is left to wonder: How did 2 terrorists come from here?

At an Orlando hospital, the victims kept coming — but so did an army of nurses

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.