On the road in Texas, where all the roads look like rivers

- Share via

Reporting from Fort Bend County, Texas — It’s hard to explain the stupefying vastness of the flooding in Texas, the nature of the calamity named Tropical Storm Harvey, until you actually try to drive somewhere in it.

The rain falls all kinds of ways: in buckets, sideways, in little spits, or just plain regular, but the one thing it absolutely doesn’t ever do is stop. It rains in the morning, it rains in the afternoon, it rains in the evening, it rains at night. The rain is less an atmospheric condition at this point than a kind of state of being, like mourning, that can’t be forgotten unless you’re asleep.

And in the pancake-flat coastal plains around Houston, it’s clear that the water, once it hits the ground, has only one direction to go. Up over the creek beds, up over the levees, up over the roads. Up into your shoes, up into your house, up into your life.

In Fort Bend County, west of Houston, at least 20% of the population has been asked or ordered to leave their homes, under threat of fine or arrest. And trying to drive in the county on Monday, it was clear why.

Fields and housing subdivisions alike have been turned into lakes, the water creeping up to the roads and sometimes over them. Cars and SUVs lay swallowed in ditches and on roads and in driveways. Their half-visible shapes are less like vehicles than tombstones. The message they offer is clear: Turn back or meet doom. The roads everywhere are filled with other warnings -- people on foot, trudging through knee-high water in sandals and carrying their things in a plastic bag because it’s the best and possibly final option they have.

And in a region designed for the driver, there is so little meaningful driving to be done. There’s another freeway on-ramp pooled in water too deep to ford. There’s another side road swallowed by a creek that has become an ocean. You consult GPS or Google Maps for arcane alternate routes like a scholar teasing secrets from an ancient text, which may or may not be true.

This process, too, is followed by more turning back.

Driving down the road in the dark, it’s impossible to tell whether the traffic coming the other way is coming from somewhere else, or if they, too, have turned back. Deep down, you know it too: Water ahead. It looms in the darkness all around, creeping up in the fields and heading your way.

Driving is ordinarily the most solitary form of transit — except here, now, due to necessity. Sometimes drivers form short columns in an unspoken agreement, like a military patrol, where a scout in front goes first and takes all the risks. If the lead driver can pass an uncertain patch of standing water, so can the rest.

It’s through such a brief meeting of strangers that this driver found a safe path late at night to the city of Rosenberg, where many of the roads downtown remained open, waterless — at long last, something safe.

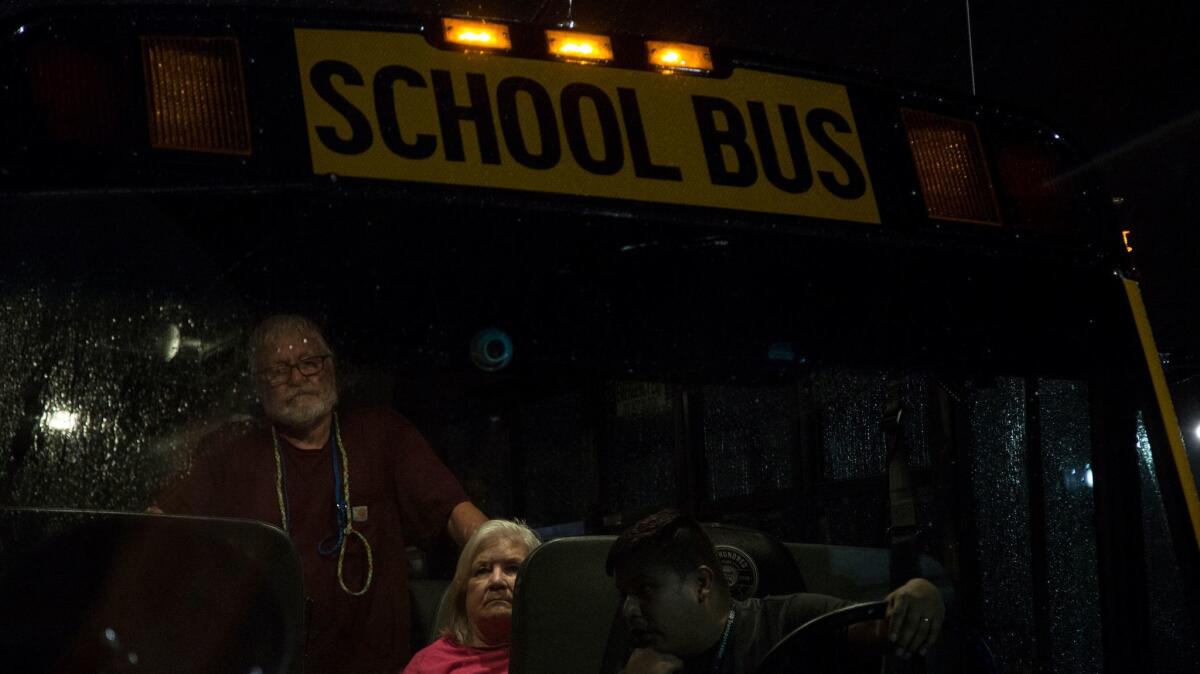

The Red Cross shelter set up at the local high school shines invitingly in the night as buses filled with evacuees roll up to the front door.

“My little car’s gone, I’m sure,” says Janet Hamilton, 62, an evacuee from Bay City, about 65 miles southwest of Houston, as she smokes a cigarette outside the shelter’s front doors. Before fleeing her home, she’d put her grandmother’s picture of Jesus (circa 1931) and a family photo album on the highest surface in her house, hoping the waters wouldn’t reach them. Then she ran.

A self-described Texas weirdo, Hamilton thought she’d seen it all from hurricanes. Hurricane Carla in 1961, Hurricane Alicia in 1983, “they come in, they rock ‘n’ roll a little bit, and then it’s gone,” she says.

This time, she only had 15 minutes to pack as police officers trawled her town and said they had to evacuate — now — or go to jail. Not because of hurricane winds, but because of hurricane rains.

“I’ve been here all my life,” Hamilton says, winding up to the words every Texan who isn’t unconscious must be thinking right now: “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

ALSO

Gulf Coast braces for more rain as Harvey makes second landfall

Here’s what we know about Tropical Storm Harvey: Rain, flooding and people needing rescue

‘A true testament to a mother’s will’ — saving her daughter, but not herself, from Harvey’s floods

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.