American militias have a long history on the U.S.-Mexico border

- Share via

An armed group in New Mexico whose leader faces federal firearms possession charges drew national attention recently for detaining asylum-seeking Central American families near the U.S.-Mexico border.

The United Constitutional Patriots say they want to draw attention to immigration violations and help federal law enforcement in patrolling the border. The group is led by 69-year-old Larry Mitchell Hopkins, who was indicted last month on charges of being a felon in possession of firearms and ammunition. He was previously convicted for impersonating a police officer and repeated firearms violations.

It’s not the first time an armed militia patrolled the border amid immigration and racial tensions. Throughout U.S. history, private armed groups have been hired or appointed themselves to police the U.S.-Mexico border for a variety of reasons, including preventing slaves from fleeing and stopping Chinese immigrants from crossing over illegally.

Here’s a look at the history of armed groups patrolling the border:

Slave patrols

After the Mexican-American War, slave-hunting groups began monitoring the border between Texas and Mexico and watching for slaves who had run away.

Slavery had been abolished in Mexico, and slaves from as far as Alabama sought to escape to Mexico through the southern Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

Historians say the armed horsemen sometimes went into Mexico illegally to try to capture runaway slaves but were met with resistance from the Mexican government and people. Mexico refused to return the slaves who fled there.

University of Texas doctoral candidate Maria Esther Hammack has documented how Mexican Americans helped runaway slaves avoid the patrols and escape to Mexico in the mid-1800s.

Texas Rangers

The Texas Rangers were recommissioned after the Civil War. Although the group was known for fighting Native American tribes and alleged bandits, historians say it also functioned as a private militia on behalf of wealthy landowners and ranchers concerned about cattle and horse thefts.

During the early 1900s, the Texas Rangers operated with impunity along the Texas-Mexico border on the grounds that they were protecting U.S. residents from Mexican outlaws who would cross over and raid ranches. But, according to historians, the Texas Rangers often attacked Mexican Americans in Texas border towns, raiding homes without warrants, torturing suspects and sometimes killing innocent people.

Tensions were especially high during the Mexican Revolution as refugees attempted to cross over and escape the violence. In 1919, the Texas Rangers executed 15 Mexican American men and boys from Porvenir, Texas, in what would later be called the Porvenir Massacre. None of the Rangers served jail time, but the massacre would later lead to reforms.

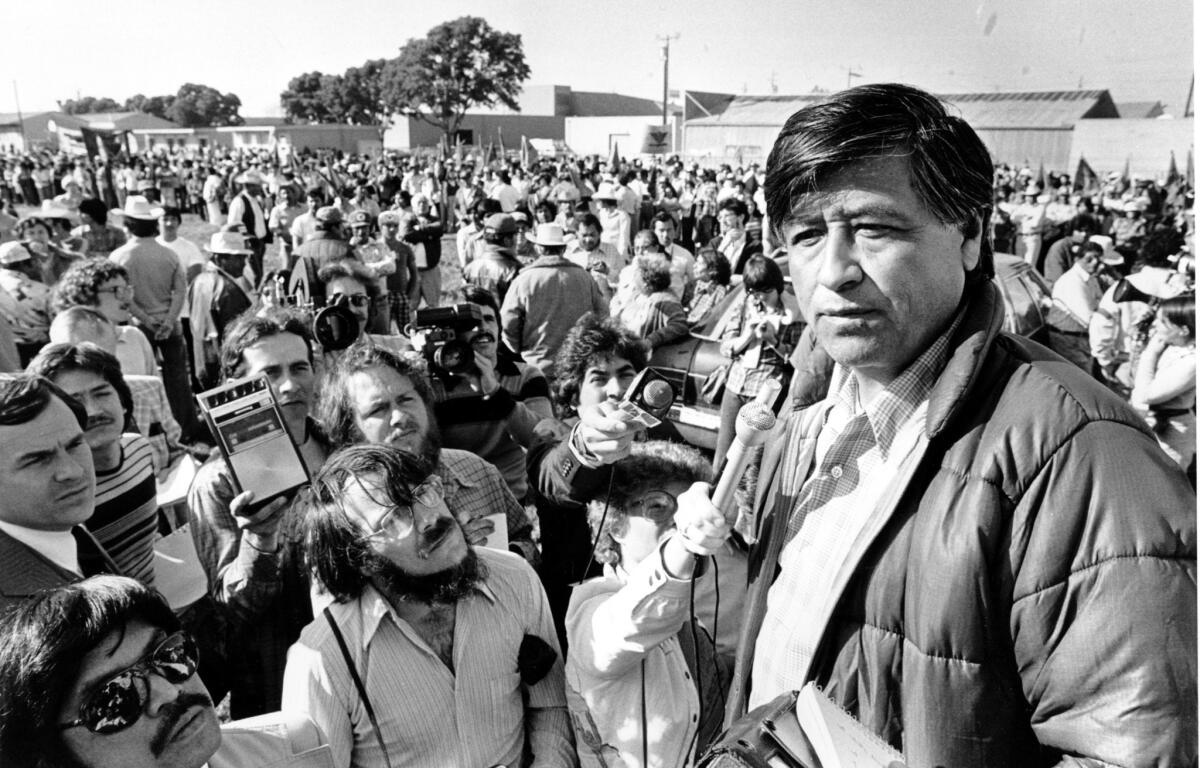

Cesar Chavez and ‘The Wet Line’

After World War II, many Mexican American civil rights leaders openly expressed alarm at the growing number of Mexican immigrants coming into the U.S. illegally. They also felt white businessmen and ranchers used the immigrants to keep the wages of Mexican Americans low because they couldn’t unionize. Cesar Chavez, the co-founder of the United Farm Workers of America, believed white growers used Mexican immigrants as strikebreakers.

In 1973, members of the United Farm Workers under the guidance of Chavez’s cousin Manuel set up a “wet line” along the U.S.-Mexico border near San Luis, Ariz., to halt Mexican migration. (The term “wet” refers to a racial epithet aimed at Mexican immigrants.) Manuel erected 17 tents along a 25-mile stretch of the border and had members physically attack migrants. The Yuma Daily Sun newspaper reported that cars were torched, men were beaten with a plastic hose and one man claimed attackers burned the soles of his feet.

Miriam Pawel, in her 2014 book “The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography,” wrote that the Mexican labor federation — the Confederación de Trabajadores de México — broke with the United Farm Workers and denounced the “wet lines” as a campaign of terror. The labor group’s leader, Francisco Modesto, said hundreds of beatings occurred and two men were castrated.

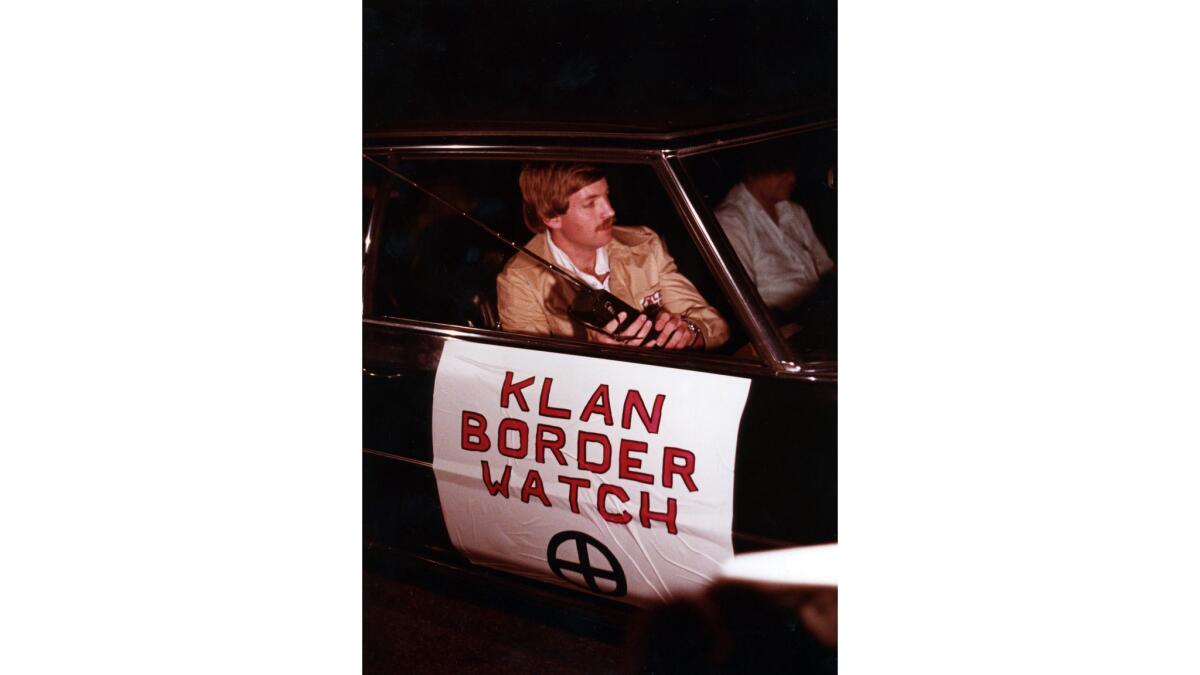

White Supremacists

In 1977, then-Ku Klux Klan national director David Duke announced that members of the white supremacist group would patrol the U.S.-Mexico border. He said armed members would assist the Border Patrol in stopping immigrants from getting into the U.S. illegally.

The Border Patrol in the 1990s, under President Clinton, a Democrat, increased enforcement in urban areas like El Paso and San Diego, and migrants started shifting their path through the Arizona desert, prompting militias to form. The groups were accused of unlawfully detaining Latinos and in some cases of physically attacking them.

Among the groups was the Minuteman Civil Defense Corps, founded by Chris Simcox and J.T. Ready, a former neo-Nazi. The group urged citizens to take it upon themselves to guard the region.

Glenn Spencer also created the American Border Patrol in southern Arizona and touted it as a “shadow Border Patrol.” The Southern Poverty Law Center lists the American Border Patrol as an extremist group.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.