Reddit cofounder Swartz struggled with prosecution before suicide

- Share via

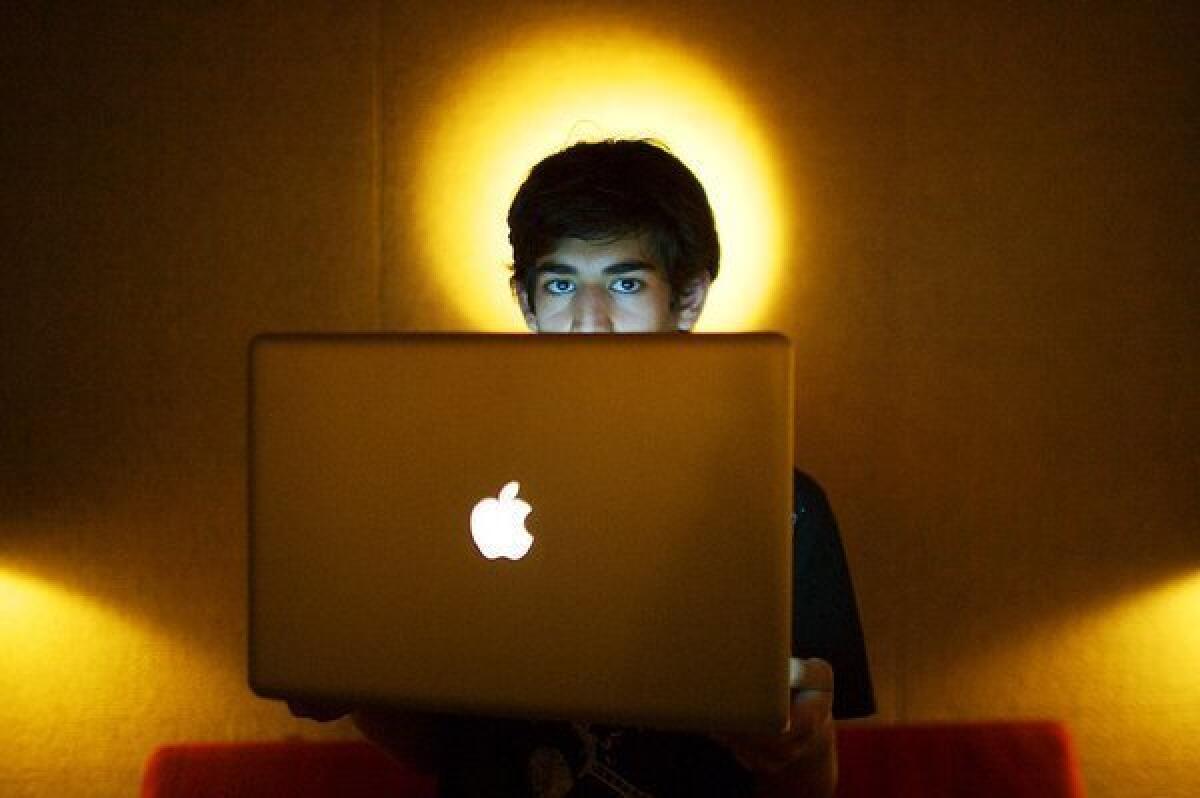

Aaron Swartz saw a closed world and wanted to crack it open. His suicide by hanging in New York last week has reignited the conflict between the values of property possession and digital openness and intensified debate over the government’s determination to send him to prison.

In Swartz’s world, data constituted knowledge, and knowledge demanded to be shared. In service of that goal, he helped start Reddit, a news and entertainment website, and RSS, the information distribution service.

He was also a formidable hacker, which led to an indictment in Boston for wire fraud and the possibility of 35 years behind bars.

According to his girlfriend, aggressive prosecution and the embarrassment of asking friends for help and money as part of a defense campaign wore down Swartz, 26, who had a history of depression and was battling the flu.

“I was never as worried about him as the last few days of his life, and there’s no doubt in my mind that this wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been for the overreaching prosecution,” Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, 31, said in a phone interview from Chicago, where she’d flown for Swartz’s funeral. She added, “He couldn’t face another day of, ‘Have you done this, have you asked people for money.’ I think he literally rather would have been dead.”

On Monday, as a formality in response to his death, federal prosecutors dropped multiple felony charges against Swartz, and the U.S. Attorney’s office in Boston did not respond to a request for comment. Earlier, a spokeswoman said prosecutors wanted to respect the family’s privacy.

According to the indictment, sometime between September 2010 and January 2011 Swartz physically broke into a wiring closet at MIT, where he wasn’t a student or faculty member, to hack into the school’s networks so he could download millions of academic articles from an expensive database, JSTOR. Authorities said he repeatedly rebuffed the school’s and the service’s attempts to prevent his downloads and planned to distribute the articles for free on file-sharing services.

Prosecutors, plus legal experts such as George Washington University’s Orin Kerr, thought Swartz’s acts clearly broke U.S. law, which bans taking “property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses.”

Swartz likely could have accessed JSTOR from Harvard, where he was a member of the university’s ethics center, and which, like most universities, has access to JSTOR’s subscription service.

The act of snatching academic work was not an act of need, however, but apparently one of politics -- an attack on the same law that Swartz himself had said contradicted common-sense values of openness and public stewardship.

In his 2008 “Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto,” Swartz wrote, “The world’s entire scientific and cultural heritage, published over centuries in books and journals, is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations. Want to read the papers featuring the most famous results of the sciences? You’ll need to send enormous amounts to publishers like Reed Elsevier.”

He added, “There is no justice in following unjust laws. It’s time to come into the light and, in the grand tradition of civil disobedience, declare our opposition to this private theft of public culture. We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world.”

Prosecutors disagreed but, notably, JSTOR did not, at least in part. The service declined to press charges after it said Swartz returned the articles. Prosecutors pushed ahead anyway, quietly supported by MIT, whose president has since ordered a review of the university’s actions.

The divergent courses taken by the government and JSTOR split even further apart last week when prosecutors declined to offer Swartz a plea deal that would have spared him prison time, his attorney, Elliot Peters, told the Wall Street Journal. The same day, JSTOR released the 4.5 million articles Swartz had taken for free use over the Internet. Swartz had won a small cultural victory, but not a legal one.

George Washington University’s Kerr wrote in a Monday blog post evaluating the government’s case: “I think the charges against Swartz were based on a fair reading of the law. None of the charges involved aggressive readings of the law or any apparent prosecutorial overreach.”

But much criticism elsewhere was aimed at the U.S. attorney in Boston for the office’s unwillingness to soften charges that could have brought a longer prison term than some homicide convictions.

On Monday, hacker collective Anonymous raided MIT’s website and placed a message alongside a tribute to Swartz: “We call for this tragedy to be a basis for reform of copyright and intellectual property law, returning it to the proper principles of common good to the many, rather than private gain to the few.”

Stinebrickner-Kauffman, who had been dating Swartz since a few weeks before his indictment in 2011, said their “entire relationship was under the shadow of this prosecution.” Swartz had initially kept a low profile about the case in the hopes that prosecutors, without political pressure, would be more lenient, she said, but that didn’t happen. He’d also hoped MIT would stand up for him, and was disappointed when the school didn’t.

“In last few weeks, we were changing strategy and we were beginning big outreach to potential allies and to friends and to build a campaign -- and that was incredibly difficult for him,” Stinebrickner-Kauffman said. “It was about the profile of the case but also about the money. ... He had dug himself into a financial hole, and there were ways out of it for sure, but none of the ways out were palatable for him. He found it so hard to contemplate asking other people for financial help.”

His death has ignited a discussion about academic research’s place in public life, with many academics posting copyrighted articles online in honor of his death.

Caryn Stedman, 57, a professor at Central Connecticut State University, told The Times that Swartz’s death highlighted what she saw as the absurdity of copyright rules.

“It frustrates me that intellectual, high-level academic material -- like the kind of juried, peer-reviewed articles published in various journals like JSTOR -- are not available to people outside the academic community,” said Stedman. “Since none of us gets paid for writing this material, I feel that it should be in the public domain.”

Stedman said she didn’t know Swartz, but knew of his activism and was appalled but his prosecution, which touched on problems she faces when she occasionally teaches at a local magnet school that lacks its own access to JSTOR.

“All of my high school students write research papers,” she said. “They say, ‘I think I found this article, but I can’t get it.’ Do I log in as my university persona and give it to them?” She added, quickly, “I’m not going to tell you the answer to that.”

ALSO:

Sandy Hook group calls for ‘real change’

George H.W. Bush goes home from hospital

Hacktivist’s death intensifies criticism of U.S. attorney, MIT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.