Jean Harris dies at 89; killer of ‘Scarsdale Diet’ doctor

- Share via

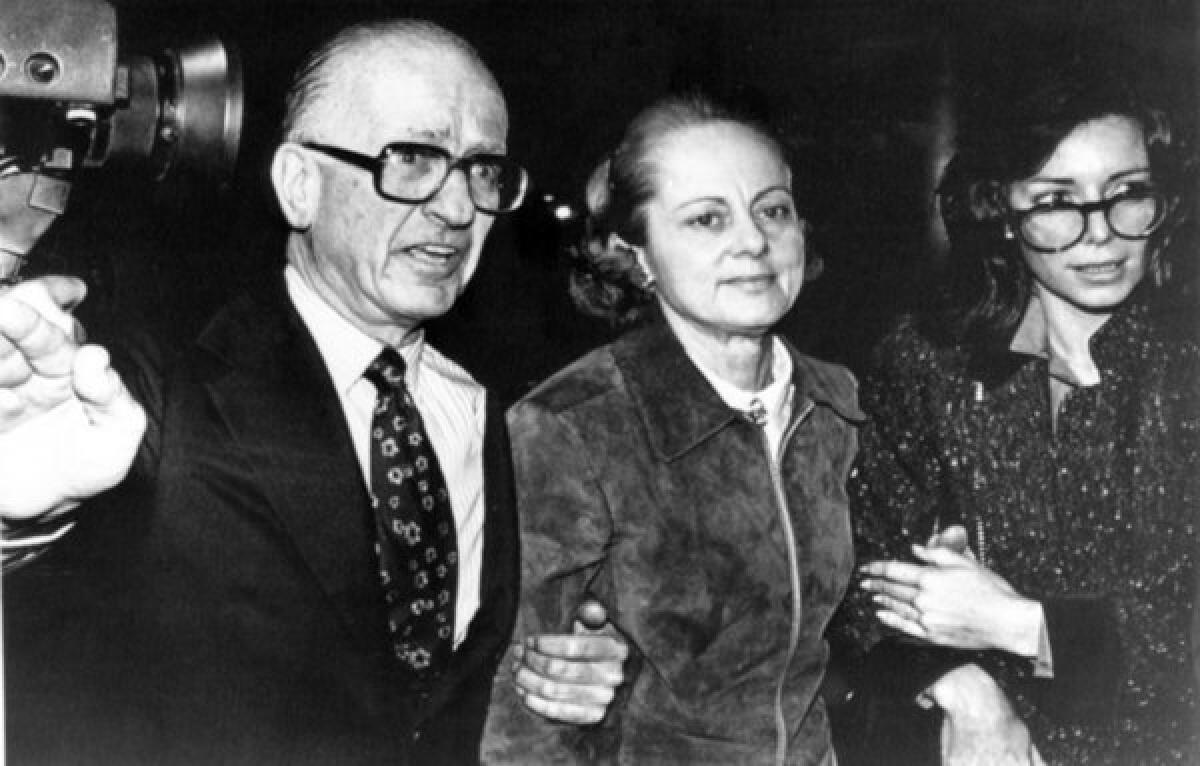

Jean Harris, the onetime headmistress of an elite girls’ school whose trial in the fatal 1980 shooting of the celebrity diet doctor who jilted her generated front-page headlines and national debates about whether she was a feminist martyr or vengeful murderer, has died. She was 89.

Harris, who spent nearly 12 years in prison for the shooting death of her longtime boyfriend, “Scarsdale Diet” doctor Herman “Hy” Tarnower, died Sunday at an assisted-living facility in New Haven, Conn., of complications related to old age, her son James said.

Convicted in 1981 of second-degree murder, Harris, who had at least two heart attacks in prison, was granted clemency on her 15 years-to-life sentence on Dec. 29, 1992, by then-New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, who cited her health and advancing age.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2012

“I honestly thought I would die in prison,” Harris said after her release.

Harris, then 68, took up residence in a New Hampshire cabin overlooking Vermont’s Green Mountains, where she walked her dog, wrote and raised money for a program to help children of inmates at New York’s Bedford Hills Correctional Center, where she was imprisoned after her Feb. 28, 1981, conviction.

The March 10, 1980, shooting of Tarnower — which she claimed throughout her life was her own suicide gone awry — was one of the most sensational crimes of its era.

FROM THE ARCHIVE: Times reporting on Jean Harris

It riveted the nation, not only because of its titillating combination of sex and violence. It raised what many experts said were important sociological issues, with some feminists rallying to Harris as a symbol of society’s disregard for the plight of older women and others arguing that her case had nothing at all to do with feminism.

Women’s movement icon Betty Friedan dismissed Harris as a “pathetic masochist” for staying with a man who mistreated her. But author Shana Alexander, who wrote a book on the case, described Harris as the “psychological victim of a domineering person.”

Whether morality play or soap opera, the case inspired two TV movies: “The People vs. Jean Harris” (1981), in which Harris was portrayed by Ellen Burstyn, and “Mrs. Harris” (2005), which starred Annette Bening.

In 1980, Harris was the 56-year-old headmistress of the fancy, private Madeira School overlooking the Potomac River in McLean, Va. Tarnower was a 69-year-old cardiologist and best-selling author of a book on a high-protein, low-fat diet that he developed for heart patients at his medical center in well-to-do Scarsdale, N.Y.

When they met in 1966, they were so taken with each other that Tarnower — a lifelong bachelor — gave Harris a 4-carat diamond engagement ring. He quickly changed his mind, telling her that he couldn’t stop seeing other women.

Harris agreed to this condition, and through the years became what she wryly described as “the broad-he-brought” to dinner parties. By 1980 the 14-year relationship was on the skids as Harris became embittered watching Tarnower, in the wake of the Scarsdale diet book, growing ever more rich and famous.

The last straw for Harris: Tarnower was “wavering” about whether to invite her or a younger woman, Lynne Tryforos, to a dinner honoring him.

After one particularly harrowing week at the school when she expelled four seniors, Harris decided on suicide. She wrote notes to her grown sons, put her papers in order, packed a .32-caliber handgun in her purse and drove five hours from Virginia to Tarnower’s six-acre estate in Purchase, N.Y.

She later testified that she wanted to see her lover one last time before killing herself at the estate’s duck pond. But her plans went awry after she let herself into his home, found Tarnower asleep and spotted a negligee and hair rollers in a bathroom — evidence that her rival, 38-year-old Tryforos, had recently stayed over.

Harris threw the hair rollers at a window, breaking it, and also broke a cosmetic mirror. The ruckus woke Tarnower, who struck her, Harris said. She said that she challenged him to “hit me again, Hy, make it hard enough to kill,” but he withdrew. Feeling the revolver in her pocketbook, she pulled out the gun and said to him, “Never mind, I’ll do it myself.”

But, she testified, when she raised the gun to her temple, he grabbed the weapon, which went off and wounded him in the hand, giving her time to grab the gun again; she later testified that she thought she had time to kill herself.

In the ensuing struggle, Tarnower was struck by bullets three more times — in the chest, arm and back. A fifth bullet also was fired. Harris maintained throughout her life that Tarnower was trying to prevent her from killing herself.

The call to the White Plains police was made at 10:56 p.m. by the doctor’s housekeeper, who lived on the estate. The March 12 four-column headline in the New York Times read “ ‘Scarsdale Diet’ Doctor Is Slain; Headmistress Is Charged.”

The highly publicized 64-day trial that followed included 92 witnesses — most disastrously, Harris herself.

Most legal experts agreed later that Harris should not have testified because, although she was bright and occasionally witty, jurors could not relate to her.

Theo Wilson, the New York Daily News reporter who covered the trial and wrote about it in the 1996 book “Headline Justice,” said Harris took the stand looking as if she couldn’t “pick up the wrong fork, much less a loaded gun.”

Also damaging to Harris was a letter she had written to Tarnower that she described as “an anguished wail, held back for many years” in which she said she had reached a professional and personal crisis.

Wilson said the letter exposed Harris as “a powerless and obsessed woman, filled with anger and self-pity … begging for crumbs at the table of Hy Tarnower.”

Like many who closely watched the trial, Wilson believed that if Harris had been willing to admit that hers was a crime of passion, she would have served a shorter sentence. But Harris would have had to admit that she killed Tarnower. Instead, she stuck to her story.

That left the jury nothing to work with, Wilson said, “except her insistence that the bullets which finished off Hy Tarnower were all meant for her.”

At the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison north of New York City, she lived in a 6-by-8-foot cell with a bed, toilet and sink. She once fashioned a pillow by stuffing her mink jacket into a prison-issued pillowcase.

During her seventh year in jail, Harris told an L.A. Times reporter that she listened to her AM radio, wrote in longhand and kept the light on at night to read and keep away cockroaches.

“One of the terrible things about prison is that you begin to get used to it. The obscenity of it, the noise of it, the waste of it,” Harris said in “Stranger in Two Worlds” (1986), one of several books she wrote while incarcerated.

Eventually her teaching skills were called upon by the prison’s Children’s Center. Harris’ tasks included teaching parenting classes and caring for babies born in Bedford who were allowed to spend a year with their inmate mothers.

Harris told the New York Times in 1993, the year after her release: “I didn’t twiddle my thumbs. Really, I got up every morning and went to school and taught. I know it was useful, and I was lucky to have that job.”

Cuomo cited this work as among his reasons for granting clemency.

Harris was born Jean Witt Struven on April 27, 1923, in Chicago and grew up in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, “comfortably upper middle class.”

She married childhood friend James Scholes Harris after graduating magna cum laude from Smith College in 1945. The couple lived in Grosse Pointe, Mich., and had two sons, but the marriage ended in 1964.

She often said she decided to leave her husband the night he angrily complained that she had not made sure their sons had brushed their teeth before bed. “Jim, It’s 10:30,” she told him, “and starting right now I’m not your wife anymore.”

She is survived by sons James and David; a brother, Robert Struven; a sister, Mary Lynch; two grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Did prison change Harris? She was asked that question constantly. Of course, she replied. For all its confinement, inanities and cruelties, it had opened up “avenues of learning and understanding that my former life could never have made possible.”

She also learned, she said, that she was a survivor, something she had never intended or wanted to be.

Luther is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writers Marisa Gerber and Elaine Woo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.